Department of State records pertaining to the US Consular Service records are in the Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State and Record Group 84: Records of the Foreign Service Posts. It’s important to keep in mind that not all consuls kept good records, and even if they did, many have been lost during wars, natural disasters, and similar catastrophes. There’s all sorts of great stuff in consular records, but it isn’t always as complete or as well organized as one might like.

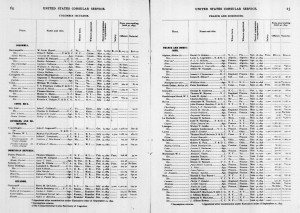

Some of the consular records — along with some diplomatic corps records — covering the period from 1789 until 1906 have been microfilmed and are available at some research libraries, through Interlibrary Loan, or in the microfilm room of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) building in College Park, Maryland. They are organized by post, then chronologically. Here’s a PDF of the published finding guide:

NARA Diplomatic Records – Blue Microfilm Guide

Keep in mind that place names may have changed, so you’ll want to look under alternate names if you don’t find what you’re looking for on the first pass.

The period from 1906 to 1910 is the Numerical File, and it’s sort of a black hole. I’ll post more information about finding things there at some point in the future. Most of it has been microfilmed, though; the trick is figuring out where the documents you want actually are. They’re somewhere, pretty much randomly, in those ca. 1,500 rolls of film.

Then the Decimal File kicks in, covering the period from 1910 to 1929, gifting the researcher with a relatively nuanced filing system. The main finding guide, including country codes, is here:

NARA RG 59 Decimal File Guide

There are post codes for the consulates, too; my transcription from the list in the finding guide available in the textual records reading room at NARA is available here:

NARA RG 59 Consulate Numbers

Record Group 59 also includes a bunch of other great stuff that hasn’t been microfilmed and is held in College Park. It ranges from the early days of the department through roughly World War II. The finding guide is available in four parts:

NARA Inventory 15 Pt I – Guide to DOS Central Files

NARA Inventory 15 Pt II – Guide to DOS Central Files

NARA Inventory 15 Pt III – Guide to DOS Central Files

NARA Inventory 15 Pt IV – Guide to DOS Central Files

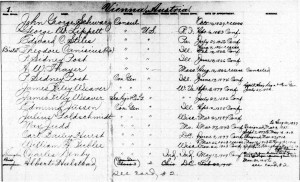

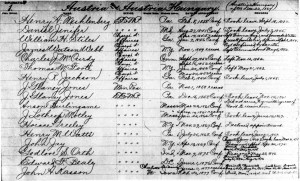

Then there’s Record Group 84. The Diplomatic Records guide mentioned above does have some information about the records here that have been filmed, but only a small number of the records fall into that category. The guide is also a bit misleading in that regard, giving the impression that the filmed records are all that exist. But there’s lots more at College Park! Most posts have some sort of records there, from account books to letter files to registers of American citizens. The basic finding guide is here:

NARA Guide to RG 84

If you go to College Park, you’ll use the information gleaned from these finding guides to consult the box lists to figure out what exactly you need to order. At this point, I don’t believe the box lists are accessible from anywhere but the textual records reading room at College Park.