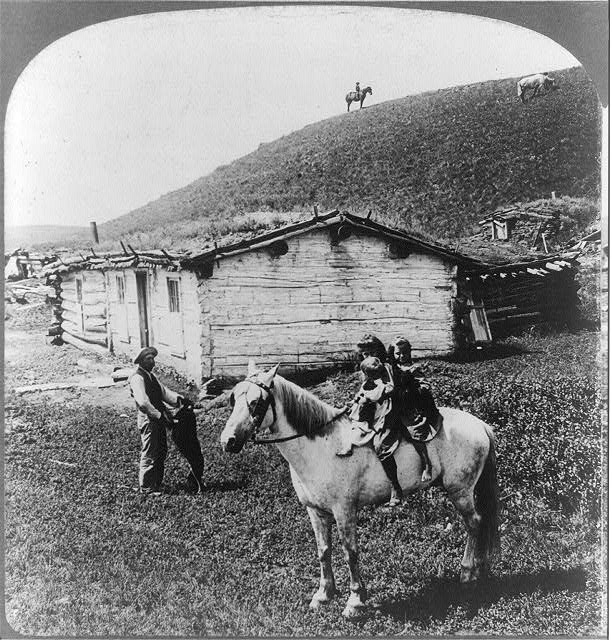

Typical log cabin of the pioneer with sod roof near Big Bend of the Missouri, N.D., U.S.A. c1908 Dec 4. International Stereograph Co. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Since dogs have been domesticated, they have shared a special bond with humans, and with children in particular. Dogs have been viewed as protectors and guardians, loyal playmates, and even role models during their many years by children’s sides. In the 19th and 20th centuries, dogs were often featured in portraits alongside upper-class children, as well as in photographs of lower-income children living on farms or in cities. Between 1850 and 1950, dog ownership became much more commonplace and socially acceptable among those who were not considered wealthy. According to Emma R. Power, “Prior to the Victorian era, people who kept pets were subject to criticism and ridicule, social conventions that only the elite could ignore”. As children became much more valuable and cherished in society between 1850 and 1950, dogs did as well, although their treatment and relationship with children varied based on certain systematic factors. Although there is less documentation of pet ownership among the lower classes in this time period, it is believed that pet-keeping was practiced in all classes and ethnic groups, and became a part of the daily lives of children nationwide. Dogs were seen in different spheres as either good, innocent creatures with the ability to convey lessons of virtue and empathy, or as immoral pests, capable of spreading disease and corrupted values to children. This duality describes the majority of child-dog relationships during this time, and can be extrapolated to provide insights about the contradictory practices and ideas of American society. To children, dogs served the purpose of teaching them morality and class-coded values, though their perception of and relationship to dogs differed along the lines of class, race, and geographical location.