Dogs offer insights to the construction of historical childhoods in many different ways, which are detailed below. To some, dogs were considered treasured companions and in fact mentors to children, with a latent purpose of teaching them the values of having a good moral compass and being kind to all creatures. In other settings, however, dogs were feared, and considered a threat to children, with public health panics like rabies (which was referred to as hydrophobia) informing many policy decisions regarding the treatment of dogs. Like children, dogs were treated differently depending on social class, lineage, and location. Although dogs are considered an important piece of today’s American identity, many children growing up between 1850 and 1950 had significantly different relationships to dogs than children growing up today.

Dogs and Morality

When it came to teaching morality, dogs served as common characters in children’s literature. In The Story of Cecil and his dog, or, The reward of virtue, by James Miller, published in 1863, an impoverished boy named Cecil encounters an injured dog: “‘Get away from me,’ said Cecil, angrily pushing him with his foot; but immediately his conscience reproached him. ‘I prayed God to have pity on me, and I have no pity upon a poor beast!’ And he took the dog in his arms, and caressed it” (35). As the story goes on, 12-year-old Cecil forms a deep bond with the dog, who teaches him many lessons about empathy, love, and godliness. Another children’s story featuring an injured and vulnerable little dog is Little Tom Grubb and his wonderful dog, published in 1860 in a children’s collection of fairy tales. When the dog appears and his brother tells him to leave her alone, Tom states, “Don’t you know father says that kindness to dumb beasts is a duty, and whoever hurts them shows a bad heart. Poor thing- poor little doggie!” (6-7). Later on in the tale, it is revealed that the dog can speak, and saves Tom from harm, favoring him over his brother because he showed her empathy. Both of these stories reiterate the theme of treating all beings with kindness, and the rewards from God that may follow if one does so. These values, however, were distinctly race and class-coded (Fielder, 164), targeted primarily toward young white boys. Finally, the contrast seen in these stories of the dog as a “dumb beast” vs. a beloved companion reveal the changing attitudes seen toward dogs in the late 19th century. At this time, animal rights essentially grew alongside those of children: “the first animal protection society in the United States had begun in 1866; by 1908 there were 354 active anticruelty organizations in the United States. Of these… 185 of them, were humane, or dual societies; 104 were exclusively animal societies; and 45 were dedicated solely to child protection” (Pearson, 2). In the worldview projected by these stories, both children and animals were helpless beings that were in need of protection and care.

Child holding a dog sitting on steps of a boarding house, New Orleans or Charleston, South Carolina. c1920s. Arnold Genthe. Library of Congress.

Dogs and Inequality

Children’s and families’ experiences with dogs and pets differed greatly across lines of class, race, and geographic location. In a rapidly industrializing America, it may have seemed at first that dogs had no place in the city. In the late 19th century, dogs are pets were commonplace among rural, working-class families that needed them for the purpose of hunting or herding. Dogs and children often worked side by side in these agrarian settings. Towering skyscrapers, smog, and crowded streets were indeed a sharp contrast to the pastoral notion of a collie herding sheep in a wide open field. Although dogs maintained their place as members of the family in urban settings, too, stray dogs were viewed with disdain. In the 19th-century city, “dogs on the loose threatened disease, bodily harm, and sheer nuisance. Debates over animal control… reflected larger struggles over how to regulate city life and ensure public health and safety in an age of intense class conflict and endless rumination over the alarmingly tenuous state of the urban social order” (Wang, 1001). As time wore on, however, more and more middle-class families began to keep dogs as pets as income levels increased nationwide, and organizations such as the ASPCA sought to regulate the stray dog population in urban areas. Later on in the century, during times of increased wealth and consumerism, city dogs came to be seen as status symbols living in relative luxury compared to their rural counterparts. A 1944 LIFE Magazine article, City Dogs, reads, “deprived of wide open spaces, they are just as happy and healthy as country dogs and live years longer”. The piece is accompanied by photographs of prominent citizens and celebrities with their dogs going for walks down bustling city streets. Dogs quickly became a part of the middle American dream, a white trope in a burgeoning cult of domesticity. For African American children, however, the idea of pets and domestication drew troubling parallels. Brigitte Fielder writes of children’s novels: “…[the] ‘master’ rhetoric seems ill suited for an African American audience. The analogy in which an African American child might identify with an obedient dog leaves antiracist readers uneasy” (167). Much later on, African American children began to be featured in the media accompanied by canine companions. A notable example of this is in the film series Our Gang of the 1920’s and 30’s. An ethnically diverse cast of characters appeared alongside the beloved Pete the Pup, including the character Farina, played by Allen Hoskins, the most popular African American child actor of the 1920’s. Although racial inequalities were reflected in the show, it gave these children one opportunity to see someone who looked like them on the big screen interacting with a lovable pet dog.

Dogs and Income

| Year | Average Income | Average Consumption Expenditures Total | Average Consumption Expenditures on Food |

| 1874-1875 | $763 | $738 | $427 |

| 1935-1936 | $1,518 | $1,463 | $508 |

| 1950 | $3.923 | $3,925 | $1,205 |

| Year | Average Income

(Highest Income Class) |

Average Consumption Expenditures Total | Average Consumption Expenditures on Food |

| 1874-1875 | $1,383 | $1,212 | $618 |

| 1935-1936 | $3,450 | $3,093 | $1,021 |

| 1950 | $13,292 | $10,342 | $2,656 |

Consumer Expenditures, 1874-1950

These tables depict the average household incomes and expenditures in the United States over 75 years, as well as those of the wealthiest class (income level adjusted). Children in the wealthiest class were were the most likely to grow up with pure-bred dogs that offered companionship or even served as “nannies”, as opposed to lower-income children, whose dogs often worked alongside of them, hunting or herding. The amount of money available for “leisure” products such as dogs skyrocketed during this time period, and the number of pets in America greatly increased.

This chart displays the Dow Jones Industrial Average stock market index between 1915 and 1950. It depicts the rapid growth during the 1920’s, the Great Depression, and the economic revival that began to occur in the 1940’s and 50’s. This data is indicative of the performance of the industrial sector of the American economy. Favorable economic conditions made families much more likely to be able to afford pets.

Small boy standing outdoors with dog. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. 1917. Lewis Wickes Hines. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

The link below displays a timeline of American views towards dogs and how these views changed over time. Myriad social trends and changes in public policy had significant impacts on dogs, and their role in children’s lives.

Public Perception of Dogs Throughout Time (Timeline JS)

Dogs, Children, and Location

The link below leads to a visual map depicting the lives of children and dogs in a variety of locations across the United States.

Urban and Rural Dogs (Storymap JS)

Significant differences in attitudes surrounding dogs and children were seen between cities and the countryside, to a much greater extent than differences between northern and southern locations, or eastern and western. Children living in the country were widely regarded as more innocent or pure than city-dwelling children, and the same can be said for dogs. Many children lived in poverty or even homelessness in America’s cities during the industrial revolution in the United States, and the majority of these children were immigrants from other countries, who were looked down upon in society as being of inferior stock. These children were much less likely to keep dogs as pets, and saw dog ownership as largely something restricted to wealthy families.

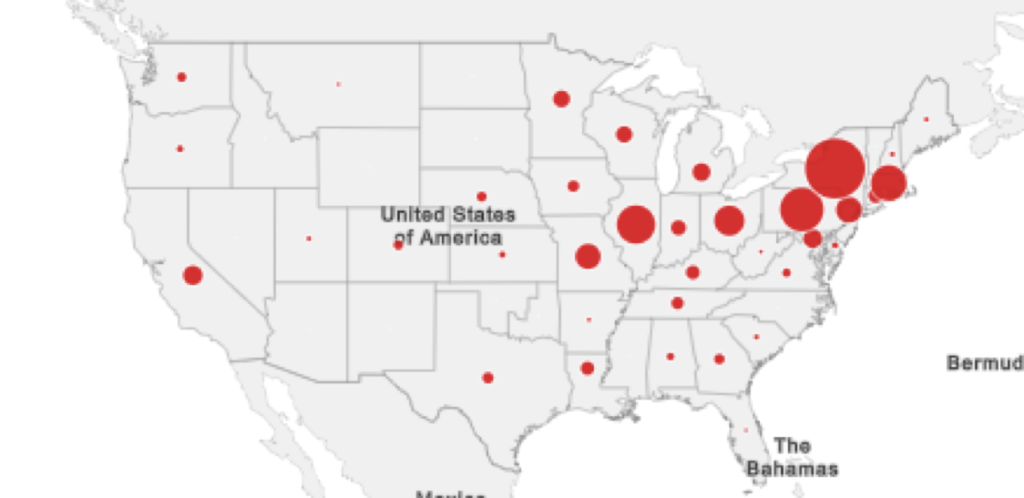

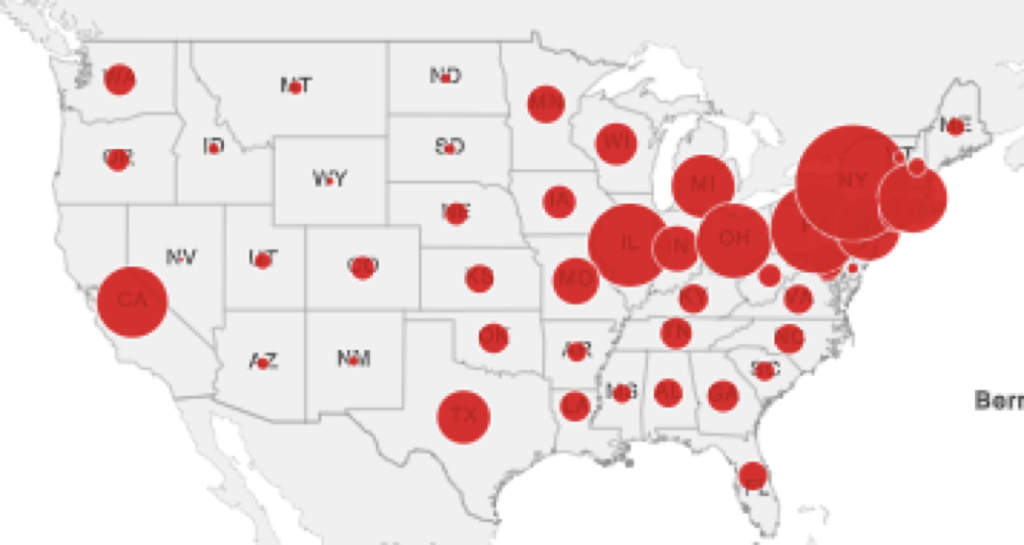

Urban Population, 1900 and 1930

https://www.socialexplorer.com/aee4fd93e1/view

These two maps depict ever-increasing urban population in 1900 and 1930, with the larger circles representing more residents. Even after the initial industrial boom, cities continued to grow, and more and more children and dogs experienced an urban lifestyle. Some children were employed as dog catchers in major cities, while others kept the company of strays, which led to increased anxieties about bites and disease, and a serious need for animal control reform.

Boy and dog. 1921. Harris & Ewing. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

In these environments, it was much less likely for dogs and children to form personal bonds, and have as great of an influence over one another. Many of the dogs lower-income urban children encountered were in fact strays, or vicious fighting dogs owned by other residents or neighbors. In fact the stray dog problem led to employment opportunities: “dog catching was just one of the numerous street trades pursued by children” (Jessica Wang, 1005). This occupation was widely unpopular and considered immoral, a pursuit that was contradictory to the natural bond children and dogs seemed to share. According to Wang, “In June 1874 Henry Bergh… targeted the bounty system for corrupting the morals of young people. ‘With a bribe of fifty cents,’ he warned darkly, ‘the idle youths of this City have been, in many instances, for the first time seduced into the temptation of stealing and betraying their friendly companions, the dogs'” (1006).

The plight of these stray dogs in many ways mirrored the conditions of the tens of thousands of unwanted children that wandered the streets of America’s cities, vulnerable to disease, violence, and starvation. Rural America was quite a different story. Many families lived on farms, with a great deal of open space for children and dogs to run around experience freedom. Dogs lived, worked, and played alongside rural Americans, and as movements such as the Orphan Trains encouraged the relocation of urban children to these idyllic locations, they were considered for a long time the best place for dogs as well. As time wore on, dogs became much more accepted members of urban society, but it was not without a great deal of suffering and social change.

Children playing near dead dog, South Side of Chicago, Illinois. 1941. Russell Lee. Courtesy of Library of Congress.