Material Culture and Social Inequality

Because dolls are such a popular aspect of child’s play, there are countless varying styles of dolls across place and time. Even between 1850 and 1950 in the United States, dolls constantly evolved. Children played with everything from rag to porcelain dolls. The preciousness assigned to each of these dolls correlated directly to the materiality of the doll. White dolls were revered as the most beautiful dolls because of the wide-held societal belief that white children were the most beautiful. Toni Morrison’s novel, The Bluest Eye, describes the impact white dolls had on black children. The novel’s narrator, a young black girl, demonstrates severity of the impact by saying, “I had only one desire: to dismember it. To see of what is was made, to discover the dearness, to find the beauty, the desirability that had escaped me…all the world had agreed that agreed that a blue-eyed, yellow-haired, pink-skinned doll was what every girl child treasured,” (Morrison 1972 in Frever 2009, 123).

Boyle, L. 1937. Thee black children playing with dolls and alphabet blocks at Delta Cooperative. Southern Tenant Farmers Union Photographs, 1937 and 1982. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives: Ithaca.

However, it was not just the white dolls that impacted how black children saw themselves, but it was also popular depictions of black dolls that shaped black children’s self-esteem. The linked timeline goes through the history of derogatory depictions of African Americans. Not until the late 1940s did the world begin to see the impact of an overwhelming white doll market with only sparse, caricatured portrayals of black dolls had on black children. This realization inspired Sara Lee Creech to attempt to create the first “anthropologically correct” doll for African American children in 1949 (Patterson 1994, 148). Though Creech’s attempt was noteworthy, the Sara Lee doll itself never did rise to popularity or mainstream success.

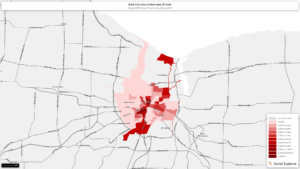

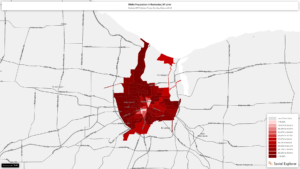

It is impossible to separate the materiality of black dolls and the view and treatment of actual black children in the United States during this time period. As black families were segregated from the daily lives of white families, the only way for white children to develop a schema of black people were through prominent objects of childhood, like dolls and literature. A study performed by the Strong Museum in Rochester, New York interviewed 97 women who played with dolls in their childhood during the early 20th Century. This study showed that if a white child did have a black doll she would not bring it over to a friend’s house to play, even owning a black doll was considered “socially inappropriate” (Thomas 2005, 115). As shown in Map 1 , the white children and the black children in Rochester were segregated form one another, making scripted material objects the only way white children could interact with black children.

Map 1: The spatial segregation of the black (top) and white (bottom) population in Rochester, NY in 1940

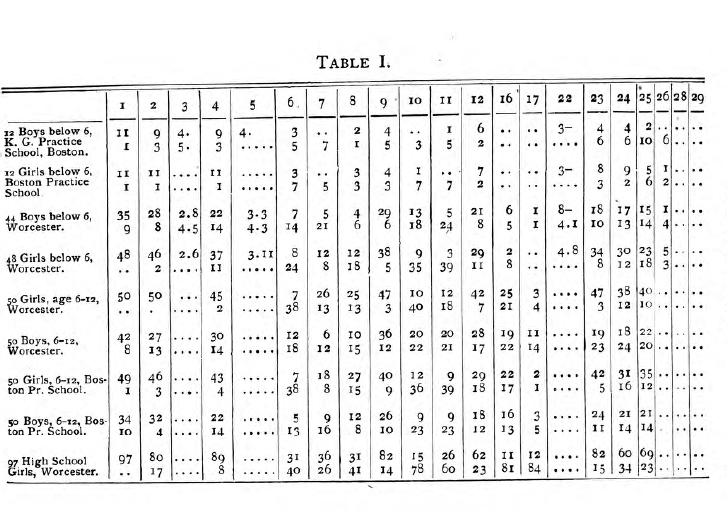

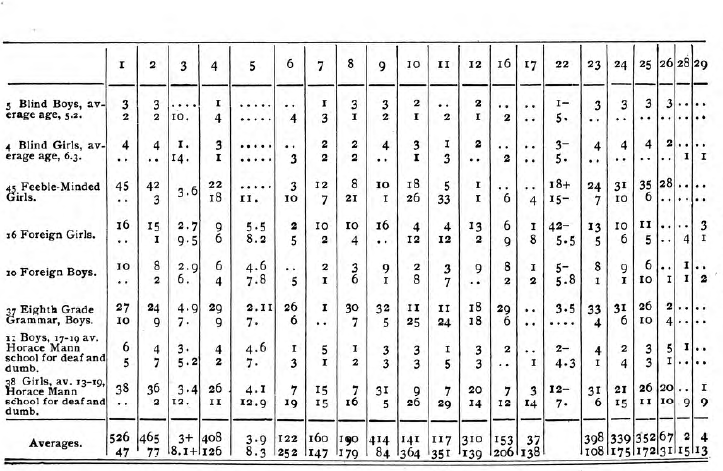

This phenomenon is not newly noted. A study performed by Dr. Stanley Hall in 1924 in Worcester, Massachusetts documented the way children played with dolls (Figure 1). Though his study did not specifically ask any questions regarding the race of the dolls, his results found that the children overall had less regard for caring of their black dolls. One child remarked their black doll did not need clothes “because they are so black nobody can see,” (Hall 1924, 11). A boy, age 11, wrote “I could not get my doll clean because he was black,” (Hall 1924, 33). Halls’ results were no were near the most graphic. Some children, who had only ever seen black people through literature, engaged with their dolls in the ways they read. These children whipped their dolls and sold them at slave auctions (Bernstein 2011).

Figure 1. The image above are the results of Stanley Hall’s 1924 doll study. The questions were as follows: 1. Did you ever play with dolls? 2. Did you specially enjoy it? 3. At about what age did you begin and stop? 4. Did you ever play with paper dolls? 5. At what age did you begin and stop? 6. Did paper dolls dull your interest for other dolls? 6. Did you ever play with anything else as a doll, such as a cat, pillow, vegetable, stick, clothe-pin, etc.? 8. Did you enjoy this as much as your real dolls? 9. Had you plenty of child companions? 10. Did you prefer playing with dolls alone or with other children? 11. Did you prefer old and well-used or new dolls? 12. Between the ages of one and six did you prefer large or small dolls? 13. From one to five did you prefer your doll to be, and be dressed as, a baby, child, or adult? 16. Did your love of dolls grow out of love for a real baby? 17. When you stopped playing dolls was it because your love was transferred to a real baby? 18. Why did you stop playing dolls? 19. Describe your favorite dolls, or any other, if you had no favorite? 20. How did you chiefly punish dolls when you were under six? 21. How when older? 22. At what age did you first play that dolls died? 23. Did you ever try to feel dolls? 24. Did you ever think your dolls were hungry? 25. Did you ever think your dolls were sick? 26. Did you ever think your dolls were cold, tired, hungry, good, bad, jealous, loving you, hating any one? 27. Which of the following ways of playing with dolls were your favorites; (1) dressing and washing, or sewing for dolls; (2) feeding; (3) nursing; (4) funerals or burials; (5) doll parties, weddings, or schools; (6) punishing; (7) putting to sleep; (8) making imaginary companions of your dolls to talk with and tell your secrets to, or to build air castles with? 28. Do you know a mother now very fond of her children who was not fond of dolls as a girl? 29. Do you know a woman who was very fond of dolls but is not now very fond of children? Retrieved from https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89088255393;view=1up;seq=7

National Identity

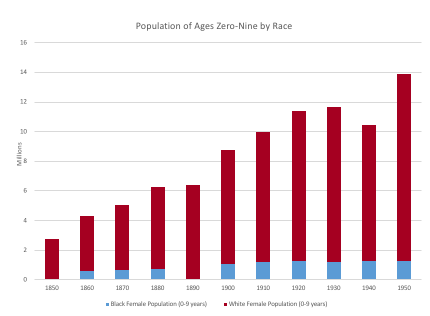

Figure 2. Black and White population ages zero to nine from 1850 to 1890. http://hsus.cambridge.org/HSUSWeb/toc/tableToc.do?id=Aa185-286

During 1850 and 1950 in the United States black people were often left out of the national identity. The census data displayed in Figure 2 shows the carelessness with which black bodies were treated during this time. In 1850 there is no recording of the black female population because slavery was still legal in the United States. Some of the 1890 census data was destroyed in a fire, but the data on the white female population was kept save whereas the data for the black female population was lost completely. However, even more than numerically were black individuals left out of efforts to create a national identity.

As tensions increased between the United States in Germany during World War One, there was a push to eliminate German made products from the U.S. market. Dolls were an especially popular German product because they had perfected the art of making bisque-head dolls. During the 1910s, toy manufacturers in the United States began to duplicate German technology and expertise in doll making to produce an American doll. The linked story map walks through the history of this feat. However, even in this process black people were left out, not only economically, but also in the finished product. Though German made bisque dolls came in a variety of skin tones, the American bisque doll was a white doll with pink-tinted skin (Formanek-Brunell 1993).