My family and I have been back from Bogotá for about a month and a half now, and though I’ve been submerged in summer teaching and finishing a new textbook on cultural anthropology for Oxford University Press, I haven’t stopped thinking about my fieldwork in Bogotá and the issues it has raised for me as an ethnographer of urban bicycle mobility. I was recently invited to give a talk on my research at the University of Vermont’s Transportation Research Center, where I am a faculty affiliate and involved in Vermont-based bicycle research. A video of the talk, entitled “Getting Around Bogotá by Bicycle: Some Ethnographic Reflections” in which I tentatively share some of my findings is above.

Do you need to ride a bike to be Colombian?

May 23, 2014 — Luis Vivancohttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Y0j8dt92Vs

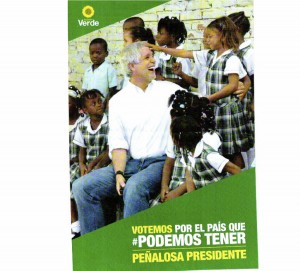

Of course not. But it seems that the presidential campaign of Enrique Peñalosa seems to think so. Watch the ad above.

Here’s a translation:

“A bicycle is something you learn and never forget. It’s about maintaining momentum without losing balance. It’s about owning your destiny, believing in your dreams, and helping others achieve their own. It’s about your own force. It’s more than a bicycle. It’s our determination to get out ahead. The bicycle unites us. There are only a few days left to elect our future. This Sunday, 18th of May, let’s pedal for Colombia.” This last bit is an invitation to join Peñalosa on what his party website calls a “characteristic ciclopaseo” in Bogotá to close the campaign.

The first round of presidential elections are this weekend, and Peñalosa’s campaign seems doomed to not survive. These elections have been especially contentious, with some pretty major mudslinging and scandalous dirty tricks between the top two candidates that commentators say they haven’t seen in a while. Those candidates, the president Juan Manuel Santos and his main rival the ultra-conservative Oscar Iván Zuluaga, have accused each other of (contra Zuluaga) hiring a computer hacker to spy on the emails of the peace negotiators in Havana and even the president’s email and then getting caught lying about it and (contra President Santos) of accepting money from drug barons.

As the acrimony has deepened, many thought Peñalosa’s chance to rise above it all and gain the lead had come, because of his consistently positive message and his distance from the traditional political machinations that generate all the corruption and political stagnation associated with the top two candidates and their parties. But his response has been surprisingly subdued and, independent of that, some key figures on the left, including the mayor of Bogotá, deserted him and aligned themselves with the President to avoid an ultra-conservative take over. No doubt that took some wind out of Peñalosa’s sails. In these last days a key message coming out of his campaign seems to have been to unleash the bicycle theme, ramping up the bicycle discourse and projecting the bicycle as a metaphor for what can unite the country.

This country, as one history book calls it “a nation in spite of itself,” has been profoundly divided for decades. But even as powerful a symbol of Colombianness as the bicycle is, its resonance doesn’t seem to translate very effectively to the political arena. As one bemused colleague of mine at the university reflected, “I haven’t ridden a bike in years! You have to be crazy to ride a bike in this city! People want cars.” It’s not that this individual is anti-Peñalosa or even anti-bike, but when people’s notions of bicycles are filtered in such a way, one cannot but help see the limits of Peñalosa’s gambit.

Indeed, even though levels of car ownership are among the lowest in Latin America, development economists and national economic planners are expecting the number of cars in this country to grow as incomes have risen. Currently in Colombia, for example, there are about 8 cars per 100 people, with a bit less than that in Bogotá. But the visions of economic planners is that Bogotá should aspire to become more like Santiago, Chile (25 cars per 100 people) or Lima, Peru (22 cars per 100 people). For Bogotá, a city already mired in profound mobility problems, this is a horrific vision since it would lead to a collapse in the urban transportation system, of complete immobility. One government economic planner I spoke with recognizes the problem, but seems resigned. “I know, it’s terrible. But it’s a sign of our economic growth.” It makes you wonder, if Peñalosa projected a rosy future of car-driving Colombians, would he be on top?

A Cycling President?

April 30, 2014 — Luis Vivanco Colombia is currently in the midst of a presidential campaign. With about a month to go, most commentators (not to mention citizens) are unimpressed and disengaged. Reflecting the lack of interest in the candidates, in third place right now in a number of polls is “Voto en Blanco” — literally, “a vote for the blank,” or a vote that is a political expression of abstention or nonconformity with the slate of candidates altogether. Unlike in the U.S. where abstention simply means not checking a box for any of the candidates, this is an actual vote that counts and can have political effects. If a majority of the votes go to voto en blanco, a new election will be held and the same candidates from the previous election cannot run in that election. A product of constitutional reform, it is meant to protect the liberty of the electorate to choose who it wants.

Colombia is currently in the midst of a presidential campaign. With about a month to go, most commentators (not to mention citizens) are unimpressed and disengaged. Reflecting the lack of interest in the candidates, in third place right now in a number of polls is “Voto en Blanco” — literally, “a vote for the blank,” or a vote that is a political expression of abstention or nonconformity with the slate of candidates altogether. Unlike in the U.S. where abstention simply means not checking a box for any of the candidates, this is an actual vote that counts and can have political effects. If a majority of the votes go to voto en blanco, a new election will be held and the same candidates from the previous election cannot run in that election. A product of constitutional reform, it is meant to protect the liberty of the electorate to choose who it wants.

Colombia is facing big issues that most seem to agree the presidential candidates are not addressing very effectively: ongoing civil war, a slow-going peace process that powerful conservatives don’t support, drug cartels, exploding environmental conflict in the countryside, grinding poverty, inhibited mobility due to poor infrastructure, etc. etc. etc. You won’t find anyone saying the need for more bicycles is on anybody’s political agenda.

But there is one candidate who has associated himself in subtle but powerfully symbolic ways with the bicycle, Enrique Peñalosa, the former mayor of Bogotá. I had noticed that in many of the articles in the newspaper about his campaign, though they don’t report him talking explicitly about bicycles, they often do refer to the fact that Peñalosa was getting around on a bicycle in some pueblo, or relaxing from the stresses of the campaign by taking a bicycle ride. The flyers supporting his campaign that are passed out on the streets, such as the one pictured above that was given to me today, have shadow bicycles in the background (not showing in this scan, unfortunately). And some of his campaign workers in the streets wear official Peñalosa-for-president t-shirts with images of bicycles on them.

While he was mayor of this city, he implemented the Cicloruta (cycle track) system, expanded Ciclovía, and began the reorganization of the mass transit system by building the Transmilenio bus rapid transit. While he has been considered an able urban technocrat who can get things done and has a strong vision of inclusivity-through-mobility, his general lack of charisma has him trailing in the polls and has in the past lost him many elections. (You wouldn’t know this if you were currently an American bicycle advocate–he has gained some popularity among U.S. advocates precisely for those qualities, his progressive-sounding social perspectives, and his mobility track record.)

But as the candidate of the Alianza Verde (“Green Alliance”), an amalgamation of progressives, environmentalists, and other left-leaning sectors, there is no doubt that his association with the bicycle signals certain things and is very deliberate. His green credentials, for sure, in a country where concern for climate change is growing. His “everyday man-ness” is another, though he is as distant from the masses and elite as they come. As he explained in it a recent interview in Semana magazine when asked about his “bicycle campaign,” his campaign is an expression of David vs. Goliath, a modest campaign that has rejected private funding and taking on the powerful in favor of social justice and equality. The implication here is that the bicycle is the symbol of the weak, the slow, the poor, while its implied Other, the car, is the symbol of exclusive power, elitism, and anti-humanist velocity.

I think there is also something else going on here. The bicycle can also be read as a powerful symbol of Colombianness–of Colombian success in international bicycle racing, of the fact that Bogotá has every Sunday its world-famous Ciclovía that other cities around the world have imitated, and the fact that it is a common vehicle that people–mostly poor, but also numbers of middle and upper class people as well–find practical, useful, and inexpensive, if not also fun. Only 13% of Colombians own cars; a lot more than that own bicycles–about 50%, for example, of households in this city of Bogotá have at least one bicycle, a city that is critical for any presidential candidate to win.

Peñalosa’s campaign has been on a see-saw of ups and downs. Even though he hasn’t unified the left (he eschews left-right distinctions), which remains suspicious of him because of his criticisms of progressives and his associations with right-wing expresident Uribe, a few weeks ago polls were suggesting that he would beat the current president, who is a weak front-runner, in a second round of voting. This week he’s slipped back in the polls, and is not only trailing the president but the main conservative candidate and the voto en blanco. Whether or not his subtle uses of the bicycle will make a difference, who really knows? But I do know one thing: he’s doing a better job of using the bicycle than the current president, who was widely reported for falling off a bicycle in a public event a couple of months ago.