Today I took my last visit to my phenology site for NR1 and 2. The last week of classes has been wet and rainy and as I wound my way through a hemlock stand to get to my site the path filled with squishy mud.

Not a lot has changed at my site since last week, but I was excited to see that the fiddlehead ferns I documented have more than doubled in size!

The other exciting moment of the day was that I spotted a few large clusters of eggs submerged in a marshy area next to the brook. I was able to get up close and get some pictures and apply some of the herpetology knowledge I gained in lab this week. I determined that they were most likely frog eggs since they didn’t have the extra layer of protective jelly that salamander eggs do.

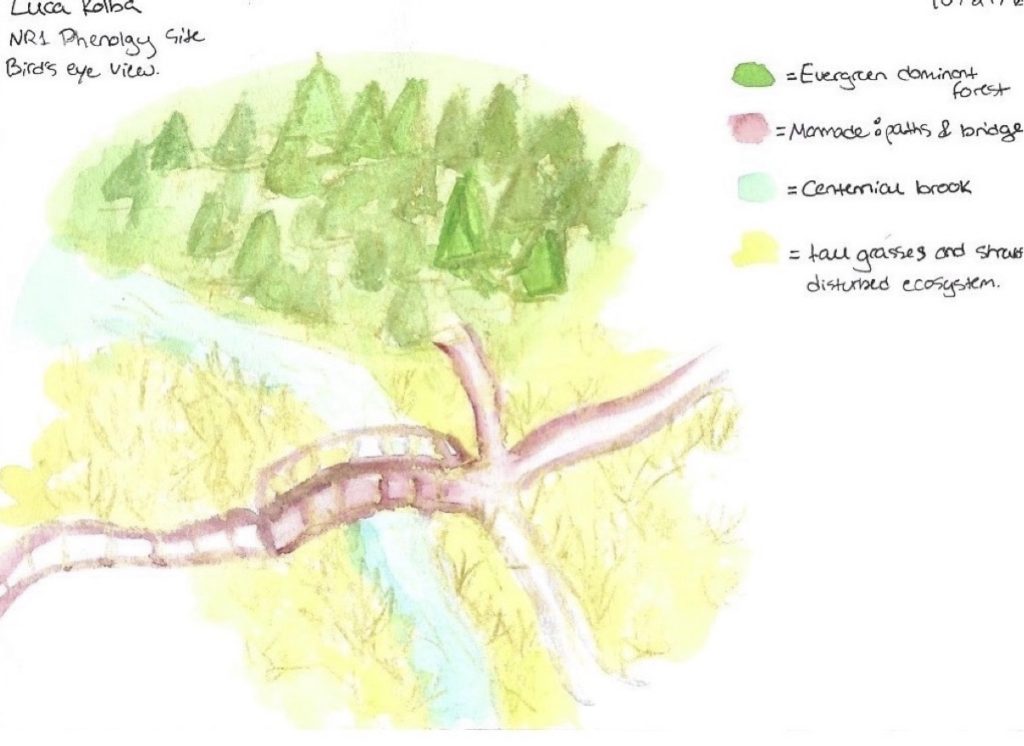

Our prompt this week was to think on how nature and culture may ‘intertwine’ at our place, and whether we see ourselves as part of our place. I think my site is an especially interesting combination of natural and human factors. As I’ve mentioned before, since power lines run through my place, it is heavily disturbed and vegetation is cut down routinely. That happened just this spring and I was shocked at the visible difference it made. However, as is clear above, nature is still thriving at my place. In fact, I think the disturbance (although not ideal) creates a very specific environmental niche which makes it a unique area in Centennial which is mostly heavily wooded. In short, I think my site is a hopeful example of nature’s resiliency.

As for whether I feel I am a part of my place, I would argue no. I enjoy being a visitor there and respectfully coming by to observe those who do call it home (the flora and fauna), but I don’t feel I have any claim to it nor do I believe I should. Since I am not a part of my place’s natural processes or its food chain I would not consider myself a part. Perhaps if I had grown up nearby I would feel differently.

Overall I’m really happy I got to have this experience this year of becoming close to a certain location and getting to observe its ebbs and flows. I think this is an experience everyone should try at some point in their lives, and I’m sure this will not be the last I see of centennial brook.

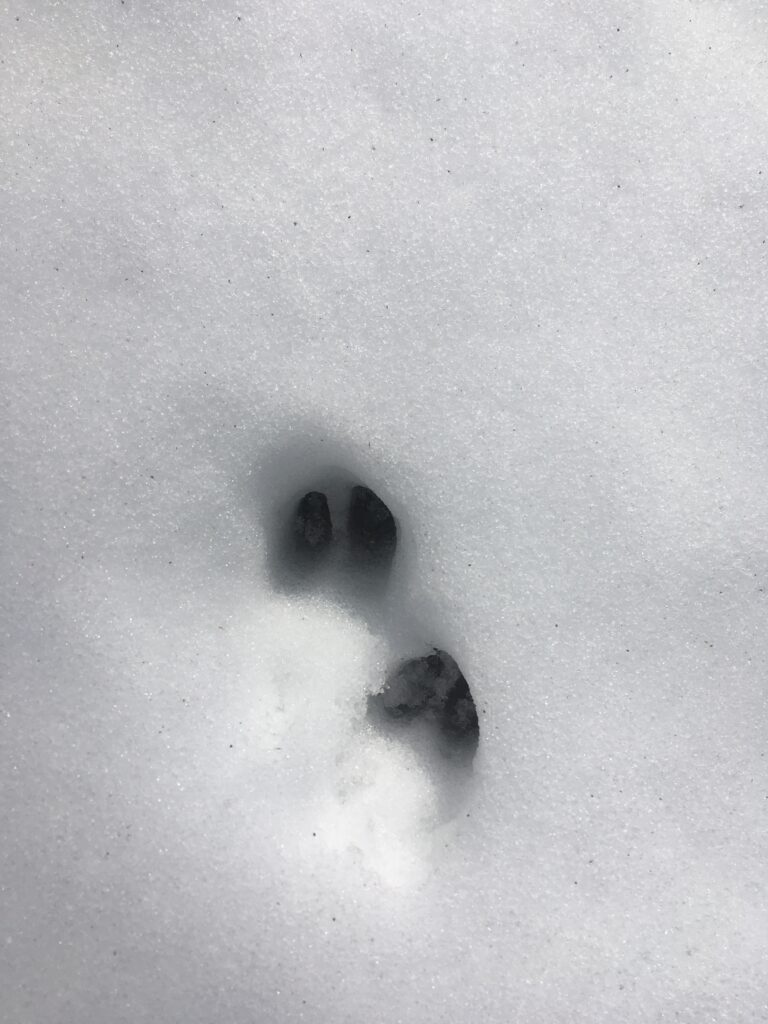

While home for Thanksgiving break this week I took my usual 5 minute trip up windy Eagle Rock Lane to Eagle Rock Reservation, 408 acres of forest nestled into dense suburban Northern NJ. My dog Gatsby, featured in the photo above, knows this drive by heart and whines with excitement as soon as he can see the rise of trees approaching as we climb up steep roads.

While home for Thanksgiving break this week I took my usual 5 minute trip up windy Eagle Rock Lane to Eagle Rock Reservation, 408 acres of forest nestled into dense suburban Northern NJ. My dog Gatsby, featured in the photo above, knows this drive by heart and whines with excitement as soon as he can see the rise of trees approaching as we climb up steep roads.