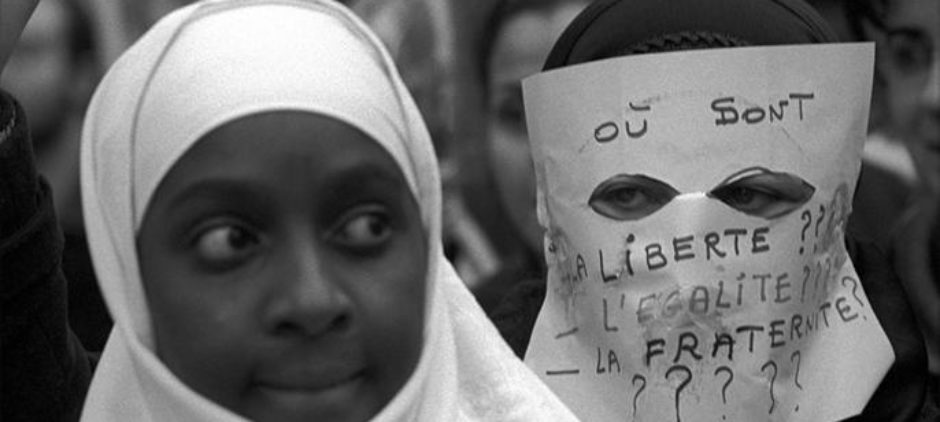

Ozbilici, Burhan. “Women shout slogans to protest against a ban on the wearing Islamic head scarves in universities, in Ankara, Turkey.” Digital image. Http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/10/131011-hijab-ban-turkey-islamic-headscarf-ataturk/. National Geographic, 12 Oct. 2013. Web. 30 Sept. 2015.

When I first saw women wearing headscarves (known as hijab) or veils (known as a niqab) I had no idea it was a Muslim custom. It was only after I heard Westerners talk about Islam and the “oppression” of Muslim woman did I realize the significance of those articles of clothing. According to the western media and certain American feminists, veiled women are seen as a sign of oppression since they are forced to wear something that men do not have to wear. (Carpenter, 2001: pg 1) This is a biased view that goes as far back as the colonial days in which colonists and Orientalists saw Muslim women as “oppressed” subjects, which in simple terms means “ women cover themselves because they are either brainwashed or forced to do so.” (Sandikei and Gur, 2010:pg 18) (Anwar, and McKay 2004: pg 722). Westerners have also used term “backwards” to describe veiled women which is a cruel way of saying that these women are primitive or un-modern. (Sandikei and Gur, 2010:pg 18)

However, I strongly disagree with this assessment. If it were a sign of oppression why would Muslim women wear veils in countries that wouldn’t force them to wear it? In fact Muslims women in Turkey are encouraged not to wear headscarves, yet many women there, have protested against the headscarf ban in Turkey. (Smith, 2013:pg 1) Why would they do that if wearing headscarves made them feel oppressed? Could it be that to them (and other Muslim women) the headscarves aren’t symbols of oppression but are rather symbols of their freedom to religion and expression? That is what I intend to explore.

In order to determine why women wear headsrcaves or veils it is best to ask veil women themselves why they put on their headscarves or veils instead of relying on accounts of people who have no experience in wearing those articles of clothing . For how can someone understand what it means to wear a veil when they themselves don’t wear one? According to Shalina Litt, a popular Muslim presenter who lectures about human rights “it was her personal choice that she wears a hijab and that she feels liberated when she wears her headscarf. Since she felt that the hijab is an expression of her faith, and modesty.” (Smith, 2013:pg 1). Homa Hoodfar also asks Muslim women how they felt about the westerners’ views on the veil and they said that they were angry and frustrated by the west’s false assumptions about the veil. (Hoodfar, 1988:pg 5) In fact, the Quran itself doesn’t state that Muslim women are required to cover their heads, although it asks both men and women to “lower their gaze and guard their modesty,” (Anwar, and McKay 2004: pg 721). To me, this doesn’t sound like the Quran is forcing women to wear certain types of clothing but rather it simply states that men and women should be modest with each other, and perhaps certain people (this includes women) feel that in order to show modesty women need to dress differently then men in order to prevent men from looking at them with lust. In fact, Fadwa EI-Guindi argues, that some feminists in Egypt have adopted wearing concealing clothing like veils and headscarves partly as a symbolic or mental shield against being treated as sex objects. (Olson 1985: pg 163) Of course that is not to say that in some countries women aren’t being force to wear veils (like in Iran), however in countries where there is a choice on whether or not women can wear veils, (or when there is a veiling ban in place) many women have decided to wear veils despite having to face heavy criticism when they choose to cover their heads. (Yusuf,2015)

It is not just biased Western views that Muslim women are frustrated with. In Turkey, Muslim women protested against the headscarf ban created by the Turkish government. Previously, this Turkish law had restricted women from wearing religious-oriented attire such as hijab and niqabs in certain civil services, political and educational places (Smith, 2013:pg 1). The purpose of this was to create a secular state that was designed to keep religious symbolism out of civil services and politics. Not only that but it was also Turkey’s attempt to become more Westernized and modern (Sandikci and Gur, 2010:pg 18). Since the Turkish government began to view the veiling as a remnant of Turkey’s Islamic Ottoman past. Therefore the government started to encourage woman to remove their veils to show their dedication to secularism. (Sandikci and Gur, 2010:pg 18) I found this amusing because Western media has stated that Muslim men force woman to wear veils, yet here is evidence of the contrary.

However while unveiling did occur, women suddenly started to re-veil in the 1980’s. Despite the fact that wearing headscarves, particularly the tesettu ̈r,had become politically stigmatized (which means that the practice has become disgraceful due to going against the norm of society) (Sandikci and Gur, 2010:pg 17). In fact the amount of women wearing tesettu ̈rs increased as more Muslim women began to wear tesettu ̈r by their own violation despite the stigmatization caused by the secularist Turkey Government and the threat at being called “backwards” by the Westerners. (Sandikci and Gur, 2010:pg 19) I find it ironic that Westerns say women who wear headscarves are backwards or primitive because surveys have shown that a decent amount of women that wear headscarves are young, well-educated, and middle class women .(Sandikci and Gur, 2010:pg 20) Which to me sounds that these women are the opposite to “backwards” since when I think of some one who is “backwards” I think of some one who isn’t well educated. In fact it was shown that doctors, teachers, students, journalists and women that are part of the municipality owned enterprise (MOE) and/or the organization for women (OFW), wear headscarves, which to me indicates veiled women are far from backwards if they have well-respected or well-educated jobs. (Sandikci and Gur, 2010:pg 20) It is also ironic that veiled women are called oppressed because it may have been oppression and the desire to fight that oppression that spurred many Muslim women to re-veil themselves. For example a prominent activist in a religious women’s organization named Serap, said that she decided to wear a headscarf after she witnessed a teacher forcing another student to take her headscarf off.(Sandikci and Gur, 2010:pg 22) She then stated that the scene angered her and after reading many religious texts she made a choice, She was either going to give up being faithful or she would take her faith seriously and practice it properly.(Sandikci and Gur, 2010:pg 22) She was not the only one, in the 1980s many educational and theological publications with the common thread of emphasizing new interpretations of Islam and a vision of life shaped by the Islamic principles, began to proliferate.(Sandikci and Gur, 2010:pg 22) In response to agreeing with and being influenced by these ideas many Muslim women with Serap line of thinking decided that if a Muslim woman was to take her faith seriously, wearing a scarf and non-revealing clothes was a duty. It is likely this obligation and duty to their faith was what led Turkish women to protest against the headscarf ban. (Sandikci and Gur, 2010:pg 22) While some critics may say that the ban didn’t stop Turkish women from expressing their faith if they wanted to since they could still wear veils in certain areas, women like Dr.Koru said the restriction abridged their constitutional rights since according to the third article of the Constitution, freedom of religion and conscience is protected for everyone and therefore women have the right to express their religion, and if veils allow them to express their religion they should have the right to wear them. (Olson, 1985: pg 161)

Overall by reading these articles and interviews I felt that I agreed with the authors in that Westerners have greatly misinterpreted the meaning behind veils in Turkey. In Turkey veils are most likely not a sign of oppression nor are they a sign of ill intent. Veils and headscarves are instead a choice that women make out of their own free will, and even if they are influenced by their interpretations of religious texts, they aren’t being forced to make the decision to put on the veil or headscarf in Turkey.

Bibliography:

Anwar, Ghazala, and Liz McKay. “Veiling.” Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Ed. Richard C. Martin. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. 721-722.

Carpenter, Mackenzie. “Muslim Women Say Veil Is More about Expression than Oppression.” Post-Gazette News [Pittsburgh] 28 Oct. 2001.

Emelie A. Olson, “Muslim Identity and Secularism in Contemporary Turkey: “The Headscarf Dispute” Anthropological Quarterly. Vol. 58, No. 4, Self & Society in the Middle East (Oct., 1985), pp. 161-171

Hoodfar Homa, “The Veil in Their Minds and On Our Heads: The Persistence of Colonial Images of Muslim Women” RFR/DRF Vol.22 No.3/4 1993 pp. 5-17

Özlem Sandikci and Güliz Ger, “Veiling in Style: How Does a Stigmatized Practice Become Fashionable?” Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 37, No. 1 (June 2010), pp. 15-36.

Smith, Roff. “Why Turkey Lifted Its Ban on the Islamic Headscarf.” Http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/10/131011-hijab-ban-turkey-islamic-headscarf-ataturk/. National Geographic, 12 Oct. 2013. Web. 1 Oct. 2015.

Yusuf, Hanna. “My Hijab Has Nothing to Do with Oppression. It’s a Feminist Statement.” Dir. Hanna Yusuf, Maya Wolfe-Robinson, Leah Green, Caterina Monzani, and Bruno Rinvolucri. Http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/video/2015/jun/24/hijab-not-oppression-feminist-statement-video. Theguardian, 24 June 2015. Web. 25 Nov. 2015.