by Ava Williams

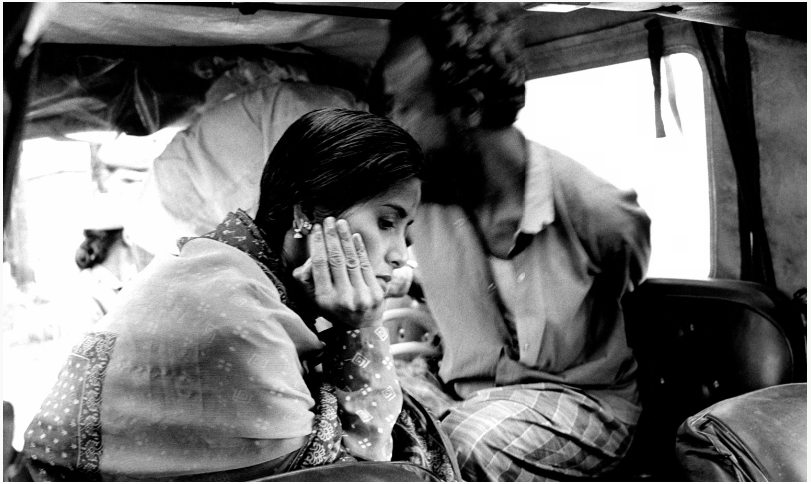

Jacob Silberberg. Muslim men take a break from scavenging through the rubbish in the Olusosun dump to pray. The Olusosun dump is Nigeria’s largest rubbish dump comprising over 100 acres of waste and is believed to be the largest in Africa. 2009.

In the early 2000s, an anti-western, Muslim organization originated in Nigeria. Formally known as Boko Haram, the terrorist organization establishes themselves against the west through their ideals and the name’s English meaning, ‘western education is a sin.’ Boko Haram has declared total Jihad in Nigeria and intends to Islamize the entire nation (Omotosho 140). Prompted by the high levels of poverty and instability within Nigeria, Boko Haram has evolved from a diverse opposition group to a terrorist organization that enacts violence throughout the state. Boko Haram targets both Muslim and Christian citizens, each of which represents about 50% of the Nigerian population, with a small percentage practicing traditional religion. The Muslim tradition has existed in Nigeria since the 9th century, while Christianity was introduced centuries later by missionaries. Yet, Boko Haram did not primarily originate from the countries religious divide. British imperialism within Nigeria created the conditions necessary for the existence of Boko Haram, and the terrorist group will only continue to spread unless concrete actions are taken to counteract the societal issues that are rooted in western modernization.

Britain’s Modernization of Nigeria:

British relations with Nigeria began in the late 18th century through increasing trade in the African continent. English traders were interested in Nigeria’s slave trade, natural resources, and the country’s’ geographically competitive location. According to Scholar Edwin G. Carle Jr., relations between the two states catalyzed around 1850 when English administrators were sent to suppress the slave trade and make the West African Coast a safe and profitable place for business and trade (79). Through increased relations, the British identified Nigeria to be a profitable territory and annexed Lagos in 1861. Scholar Emmanuel Ojo’s explains that, “Nigeria is a British creation fashioned out between 1861 and 1914. The 1861 annexation of Lagos gave Britain a firm foothold in Nigeria; and, between that year and 1903, virtually every Nigerian nation capitulated to British imperial rule”(67). Britain overtook the autonomy of the diverse Nigerian kingdoms and subjected them to a new, western government.

While Britain had control in Nigeria, they worked to implement modernization policies to make the country more economically efficient. According to scholar John Wilson, modernization is the “cultural and social attitudes or programs dedicated to supporting what is perceived as modern. Modernism entails a kind of explicit and self-conscious commitment to the modern in intellectual and cultural spheres”(6108). In terms of British modernization, the leadership sought to sow western institutions and worldviews into the Nigerian society. The British viewed themselves as the bearers of a superior society and were intent on imposing their ideology on foreign cultures. Scholar Chuku Umezurike identified the period of imperial conquest and modernization in Nigeria to have taken place between 1800 and 1945. He wrote, “The character of imperial conquest and subsequent colonization for the period consolidated comprador development through the maintenance-dissolution effects produced on peasant production relations. Thus, there has been a conjunctive exploitation of the political economy by imperial capital, traditional chiefs and mercantile middlemen”(Umezurike 37). England enacted their imperial conquest through giving Nigeria a trustee status and chartering the Royal Niger Company.

Britain sought to control in Nigeria by giving the country trustee status under British law. Charle wrote, “ This made them eligible for purchase by all British investors, including those institutions whose choice of investments was closely restricted by law. The money thus borrowed as spent by the colonial government on railroads, harbors and other public utilities”(80). Trustee status allowed Nigerians to enter the world market with the protection of British institutions. The money earned from the new trade allowed for the creation of infrastructure intended to modernize Nigerian society.

Further, Britain controlled trade through the Royal Niger Company, which the crown chartered until 1900. Charle wrote, “The company, renamed the Royal Niger Company, was granted a royal charter [in 1886] which entrusted it with governmental authority complete with full military and police powers throughout a vast section of inland Nigeria”(85). The company ordered traders to only use specific trading stations, forced native chiefs to sign away their lands and caused corruption and crime to percolate the trading process (Charle 85). Through controlling trade and having military support for their actions, the company dictated the trading processes by removing trading power from local actors and following British trading aims. British policy caused an acceleration of cultural change, and Nigerian economic gains were all accompanied by even larger gains to western entities.

The Negative British Legacy:

Although Nigeria sought to adapt to the modernization policies pushed by the British, the legacy of the British is negative. After gaining flag independence in 1960, Nigeria regressed into a military rule for around thirty years before becoming democratized again in 1999 (Akanle 33 ). This democracy has been dominated by a single party since 1999, though the nation is said to have a multi-party-political system(Akanle 33).

Many scholars argue that Nigeria is suffering in a non-functioning democracy. Umezurike wrote, “Historically, the forces of globalization, including in particular mercantilism and British colonialism, created the political and economic structures which have over the years been undermining the forces of democracy in the country”(37). The modernization policies implemented by Britain did not allow for sustainable growth for Nigerians. Most local actors were not given ownership or agency under the British, causing an unequal distribution of wealth within the country. This unequal distribution of wealth has persisted to modern days. Although Nigeria has oil-rich lands, a geographically desirable location, and the second largest economy in Africa, approximately 51 million of the 186 million citizens are unemployed, and the country has a reported poverty burden of more than 70 percent (Ojo 88). Further, the economy grew an estimated 7.6 percent between 2003 and 2010, while poverty has remained constant, even increasing in several states (Akanle 34).

The political legacy of the British has rooted corruption within the Nigerian government. Malpractice by colonial officials and the Royal Niger Company allowed for bribery and embezzlement to saturate the economy and politics (Charle 85). Corruption aided economic divisions and caused an elite group of Nigerian citizens to become successful economically. Currently, economic disparities are exacerbated by the corrupt government. Scholar Olayinka Akanle stated, “The rich and influential have hijacked political processes and machineries and now make policies against popular intentions only for the benefits of the few. The poor, who are in the majority, are consequently left in limbo”(43). The elite use their influence to take power from everyday citizens in order to gain economically. Ojo wrote, “Even with about 51 million unemployed Nigerians public office holders embezzle billions of dollars annually that could be channeled into industrial and economically productive ventures”(88). Corruption and embezzlement in the upper echelons of society have adverse effects on everyday citizens.

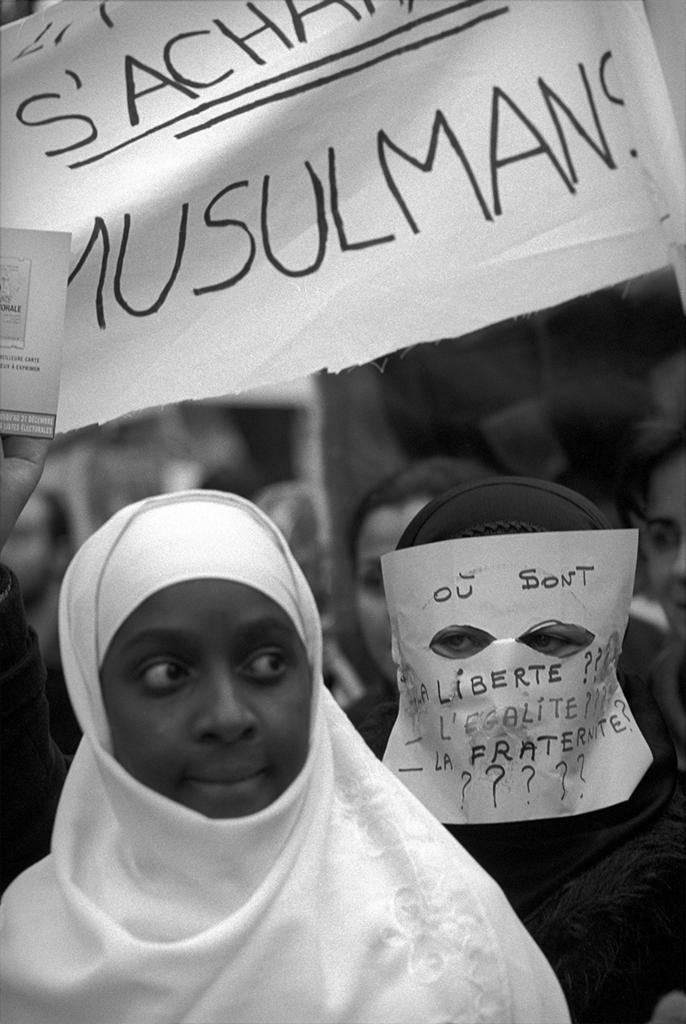

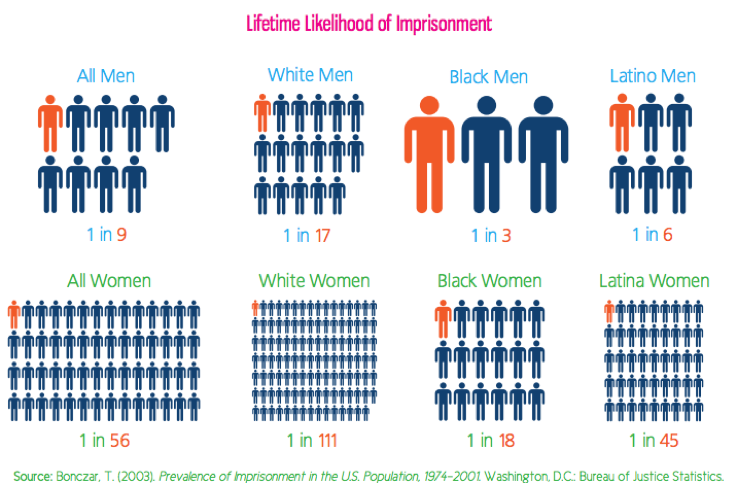

The British left a socially fractured country through their unification of the Northern and Southern protectorates of Nigeria. Referred to as amalgamation, the fusing of the territories aimed to increase the competitive economy within Nigeria, increase infrastructure, and align the developmental levels of the north and south (Ojo 69). A unified Nigeria served to make British modernization practices easier and increase economic profits. Yet, the amalgamation pushed diverse humans into a unified country, and with no policy to socially unify the north and south territories, Nigeria remained separated with an emphasis on religious difference. A feeling of distrust between Muslims and Christians stems from the amalgamation’s unification of the Muslim-majority north and Christian-majority south, who both had unique cultures, practices, and worldviews.

The religious distrust has created a power struggle; Muslims and Christians work to dominate one another. Scholar Mashood Omotosho wrote, “When military rule ended in 1999, democratic politics provided a perfect platform for corrupt and cynical politicians to play on religious rears to gain votes”(137). Politicians used existing divisions in the country to further their agendas and become elected, which contributing immensely to the problem of religious conflict in Nigeria (Omotosho 137). Although the Federal government spends millions of dollars on ‘unity campaigns’ (Ojo 71), politicians continue to exacerbate religious divisions. For example, some northern state governors are attempting to adopt the Islamic Sharia as the penal and criminal codes in their states (Omotosho 138). This is further highlighted in the anti-Sharia crisis in Kaduna in 2000, religious rioting in Bauchi state in 2001 and 2004, rioting following a Danish cartoon depicting the Prophet in 2006, and the onslaught of Boko Haram.

The Rise of Boko Haram:

The turmoil left in the wake of Nigerian modernization created the situation necessary for terrorist organization Boko Haram to take residence within the country. Founded in 2002 by Mohammed Yusuf, the group was a reaction against western modernization and had the intent to eradicate western influence in the country. Eventually, Yusuf declared total jihad in Nigeria with the threat to Islamize the whole country (Omotosho 140). The group has been enacting violence throughout the country since 2002, causing mass casualties and missing persons. For example, Ojo wrote, “Nigeria has become a country flowing daily with the blood of her citizens: about 75 people were bombed to death in a highly crowded motor park in Abuja, the Federal Capital Territory, on 14 April 2014 and on the following day about 230 college girls were abducted from their dormitories in Chibok, Borno State by members of the sect” (87). Additionally, in 2015, Boko Haram militants killed about thirty people and wounded around one hundred-forty-five others during an attack on a market in northern Cameroon, and other attacks have occurred to present day (Suleiman 22). Furthermore, Boko Haram had given Bay’ah, or pledge of allegiance, to ISIS and announced itself as the Islamic State’s West African province.

The violence has caused mass disruptions to the civil society; Every sphere of social, economic, and medical life in northeastern Nigeria is almost completely paralyzed(Ojo 86). The resiliency of Boko Haram can be attributed to domestic issues arising from political corruption, poverty, and illiteracy. These issues allowed civil unrest to transform into a large-scale terrorist organization. The conditions present in Nigeria were created by the West, and Boko Haram wishes to expel its influence from society. This means Boko Haram will only continue to spread to nearby countries unless concrete actions are taken to counteract the issues within Nigerian society that are rooted in British modernization (Omotosho 147).

British influence within Nigeria gave the country short-term economic gains but created long-lasting economic, religious, and political issues that hinder the country from effectively governing. The British acted with a lens of modernizing a non-western other, but they failed to establish institutions that were not fraught with their own self-interest. Modernization efforts created economic disparities that have led to political corruption, mass poverty, and religious friction. Boko Haram established itself within Nigeria in response to the history of Western influence within the county and the residual effects they left. Without an effective policy to expel the past effects of British imperialism in the country, Nigeria citizens may never be able to counter the dark path the country has taken.

Sources:

Akanle, Olayinka. “The Development Exceptionality of Nigeria: The Context of Political and Social Currents.” Africa Today, vol. 59, no. 3, 2013, pp. 31–48. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/africatoday.59.3.31.

Charle, Edwin G. “English Colonial Policy and the Economy of Nigeria.” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 26, no. 1, 1967, pp. 79–92. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3485317.

Ojo, Emmanuel Oladipo. “Nigeria, 1914-2014: From Creation to Cremation?” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, vol. 23, 2014, pp. 67–91. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24768942.

Omotosho, Mashood. “Managing Religious Conflicts in Nigeria: The Inter-Religious Mediation Peace Strategy.” Africa Development / Afrique Et Développement, vol. 39, no. 2, 2014, pp. 133–151. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/afrdevafrdev.39.2.133.

Suleiman, Muhammad L. “Countering Boko Haram.” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, vol. 7, no. 8, 2015, pp. 22–27. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26351382.

Umezurike, Chuku. “Globalisation, Economic Reforms and Democracy in Nigeria.” Africa Development / Afrique Et Développement, vol. 37, no. 2, 2012, pp. 25–61. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/afrdevafrdev.37.2.25.

Wilson, John, “Modernity,” Encyclopedia of Religion. Ed. Lindsay Jones. 2nd ed. Vol. 9. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. 6108-6112. Gale Virtual Reference Library.