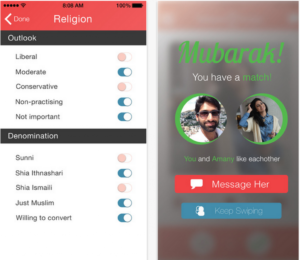

Because of the lack of inclusivity, I have decided to focus on Muslims in North America and how they are seeking potential marital partners through dating apps that have been created by Muslims specifically for the Muslim community. One app that I will highlight in this blog post is an app called Minder.  Minder was co-founded by Haroon Moktarzhada as a response to the lack of inclusivity Muslims in North America felt about pre-existing dating apps. It is inspired by the app Tinder, but caters specifically toward Muslims seeking other Muslims for marriage. Throughout my research on Minder and the use of dating apps by Muslims in North America, I have made connections to our course discussions as well as a couple interesting discoveries. For instance, I found that the use of Muslim-centered dating apps in the West is predominantly driven by Muslim women. I would not have originally thought that Muslim women in the West utilized these apps more often than men to find a potential spouse. In addition, I found that many Muslim institutions that exist in North America support the use of online dating and act as intermediaries in finding spouses for Muslims that are members of the community. As I expand on both points addressed above, I hope to bring this blog post full circle and further understand how Muslims in North America have engaged with online dating and how they have incorporated it into their culture and religion in a way that prioritizes their values. I view the creation of Minder and the use of online dating among Muslim communities in North America as a form social bricolage that allows Muslims to embrace their cultural and religious beliefs through a lens of modernity.

Minder was co-founded by Haroon Moktarzhada as a response to the lack of inclusivity Muslims in North America felt about pre-existing dating apps. It is inspired by the app Tinder, but caters specifically toward Muslims seeking other Muslims for marriage. Throughout my research on Minder and the use of dating apps by Muslims in North America, I have made connections to our course discussions as well as a couple interesting discoveries. For instance, I found that the use of Muslim-centered dating apps in the West is predominantly driven by Muslim women. I would not have originally thought that Muslim women in the West utilized these apps more often than men to find a potential spouse. In addition, I found that many Muslim institutions that exist in North America support the use of online dating and act as intermediaries in finding spouses for Muslims that are members of the community. As I expand on both points addressed above, I hope to bring this blog post full circle and further understand how Muslims in North America have engaged with online dating and how they have incorporated it into their culture and religion in a way that prioritizes their values. I view the creation of Minder and the use of online dating among Muslim communities in North America as a form social bricolage that allows Muslims to embrace their cultural and religious beliefs through a lens of modernity.

Increased number of Muslim women utilizing dating apps

Muslim women living in North America are engaging in online dating platforms more frequently than Muslim men. For instance, “we included an interaction term between gender and living in the West. The results show that the odds of women living in the West using the Internet both for arranging dates and for online dating platforms increases by 360% and 560% relative to men” (Afary 2017: 437). These numbers are extremely polarizing compared to the number of women in Muslim majority countries who use social media with the intention of dating living. This is because of some of the cultural restrictions that are imposed upon women who are living in Muslim majority countries. Moreover, “not only is there a double standard which makes women more vulnerable to sanctions for immodesty in their home countries and women are less likely to have private access to the Internet, making dating online much more dangerous for them” (Afary 2017: 437). Muslim women who are living in a western country like North America are able to navigate new spaces (cyber and pubic) that are less restrictive than those very spaces in some Muslim majority countries. This allows women to freely participate in online dating platforms like Minder, which can connect them with Muslim men who exist beyond the limits of their local social network.

Online dating via apps like Minder in North America has significantly aided in encouraging gender equality and has given Muslim women a sense of autonomy to meet Muslim men on their own terms. Minder is “like Tinder, users can swipe right if they like the look of someone and can start talking if they’re a match. Unlike Tinder, both apps allow users to filter results according to race, ethnicity, and level of religiosity” (Hamid 2015). Minder was developed by Muslims with specific emphasis on the importance of cultural and religious values. The app has also taken the perspective of Muslim women and their experiences into consideration. Furthermore, Haroon Moktarzhada states that, “In America, the expectation of what a marriage is, is very different than in more traditional, conservative societies. One of the things we tried to do with the app is be unapologetically progressive” (Majumdar 2016). This has attracted many Muslims users who tend to be more open-minded to non-conventional ways of meeting and dating a potential spouse. Not only does online forums such as Minder enhance one’s chance at meeting like-minded individuals, Minder matches individuals who may be the most compatible for each other. Online dating via Minder can “combine both Islamic marriage culture and modern aspirations of individual freedom and personal choices. It gives users, especially women, who make up the overwhelming percentage of participants, the ability and opportunity to express their personal issues, concerns, ambitions and feelings” (Lo and Aziz 2009: 17). The focus of Muslim women’s needs and the number of Muslim women using online forums such has Minder are not mutually exclusive. Since there was an initial emphasis placed on Muslim women’s experiences, there has been an increase in the use of dating apps by Muslim women.

Since I have unpacked this point, I can dispel my initial assumptions as to why I surprised that more Muslim women were using Minder to seek marriage partners. I now realize why there are more Muslim women than men who are using these apps. The combination of the mobility Muslim women experience in North America and the consideration of Muslim women’s perceptions in the creation of these apps, it is clear that the trend would reveal that more women are participating in online dating via Minder.

Muslims institutions engaging in online forums as intermediaries

Muslims institutions engaging in online forums as intermediaries

Prior to online dating forums, many Muslims in North America found it challenging to find a spouse through traditional facilitation methods. These traditional methods, however, were often inaccessible or ineffective for Muslims living in North America. As a result, many “American Muslims found spouses through diverse methods, often developing new social networks” (Lo and Aziz 2009: 6). One crucial method was the use of intermediaries to find spouses. These intermediaries often were a local imam who was connected to other Muslim communities outside of their own.

Certain Muslim institutions such as community mosques, Islamic centers, schools and local imams act as intermediators when a Muslim man or woman undergoes the search for a marital partner. For example, “there are many local Muslim communities in which members send emails to an email moderator, who confidentially matches the sender with another mate-seeker from an existing pool” (Lo and Aziz 2009: 9-10). Muslims who are seeking a marriage partner often seek guidance from their local mosque or imam because they have found it difficult to meet potential partners through family and friends. In addition, Muslim community mosques and imams are utilizing online forums to help connect Muslim men and women who are looking for a marriage partner. This has further facilitated the shift from tradition methods of finding a spouse to a more moderate and progressive method of matchmaking. Because these new methods are being implemented, it further encourages Muslim men and women to seek out other avenues like Minder.

Minder as a form of Social Bricolage

The idea for this topic has continuously progressed the further I read into the phenomenon of online dating in North American Muslim communities and how Minder has revolutionized the traditional ways in which Muslims meet, date and marry. In another course, I stumbled upon the concept of ‘bricolage,’ which is the idea that “equally, all symbolic innovations are bricolages, concoctions of symbols already freighted with significance by a meaningful environment” (Comaroff 1999: 197). The concept of bricolage just clicked and I realized that the creation of Minder within the Muslim community is, in fact, a form of social bricolage.

Muslims living in North America did not feel that mainstream forms of online dating encompassed their traditional values and as a result, many felt excluded from participating in online dating forums. However, some Muslims began to realize that many traditional methods of finding a spouse were either absent in their community or ineffective. It was extremely difficult for Muslims to meet other Muslims with marriage in mind. Dating apps like Minder began to launch within Muslim communities. The creation of Minder itself is a bricolage because it is inspired by pre-existing ideas (Tinder and Bumble) and has transformed from its original form and manipulated into something new to serve another purpose. So, in short, the creators of Minder have taken their own spin on dating apps to serve their own cultural and religious communities.

I think Minder is unlike other online forums that are geared toward other communities (Christian, Jewish, Baha’i, etc.) because it has completely revolutionized how Muslim individuals meet, date, and marry in North America. Not only are Muslims incorporating online dating praxis into their communities, but are normalizing it among both Muslim men and women alike. Minder and the use of online dating among Muslim communities in North America is a form social bricolage that allows Muslims to embrace their cultural and religious beliefs through a lens of modernity. This lens of modernity is understood through Muslim communities that value their cultural traditions and religious praxis, but also engage in contemporary forums that can enhance and further engage Muslim communities across North America.

Bibliography

Class sources:

Ernst, Carl W. “Approaching Islam in Terms of Religion.” Following Muhammad: Rethinking Islam In the Contemporary World. The University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Majeed, Javed. “Modernity,” Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Ed. Richard C. Martin. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. 456-458. Gale Virtual Reference Library.

Wilson, John F. “Modernity,” Encyclopedia of Religion. Ed. Lindsay Jones. 2nd ed. Vol. 9. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. 6108-6112. Gale Virtual Reference Library.

External sources:

“The place for awesome Muslims to meet. Swipe. Match. Marry.” Minder online. Last modified February 22, 2015. https://www.minderme.co/.

Hamid, Triska. “Two ‘Islamic Tinder’ Apps Are Being Launched for Britain’s Independent Female Muslims.” Vice online. Last modified March 25, 2015. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/8gk4nv/muslim-women-dating-minority-within-a-minority-495.

Majumdar, Shahirah. “What It Means to Date Online When You’re Muslim.” The Cut. April 28, 2016. Accessed April 24, 2018. https://www.thecut.com/2016/04/muslim-online-dating.html.

“Bricolage.” Wikipedia. March 09, 2018. Accessed March 27, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bricolage.

External scholarly sources:

Comaroff, Jean. “Chapter 7: Ritual as Historical Practice Mediation in the Neocolonial Context.” In Body of Power, Spirit of Resistance The Culture and History of a South African People, 194-251. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Lo, Mbaye, and Taimoor Aziz. “Muslim Marriage Goes Online: The Use of Internet

Matchmaking by American Muslims.” The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 21, no. 3 (2009): 1-21. doi:10.3138/jrpc.21.3.005.

Sotoudeh, Ramina, Roger Friedland, and Janet Afary. “Digital Romance: The Sources of Online Love in the Muslim World.” Media, Culture & Society 39, no. 3 (2017): 429-39. doi:10.1177/0163443717691226.

Images:

Haefeli, William. “I went on a date with him. He looks better on paper.” Digital image. Punch cartoons. 1991. Accessed February 15, 2018.

Screenshot of the dating app called Minder. Digital image. Global Dating Insights. 2016.Accessed March 05, 2018.

https://globaldatinginsights.com/2015/08/20/20082015-salaam-swipe-help-matchmaking-young-muslims/.

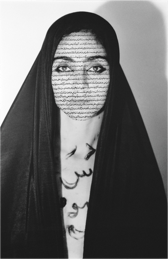

was college educated in the United States and travels between New York and Iran. In the image entitled “Unveiling” from the larger 1993-4 black and white photograph series Women of Allah, a woman directly faces the viewer, wearing a veil that reveals her neck and chest. The skin visible is covered in calligraphy. In other photographs in this series, some women hold rifles and guns.

was college educated in the United States and travels between New York and Iran. In the image entitled “Unveiling” from the larger 1993-4 black and white photograph series Women of Allah, a woman directly faces the viewer, wearing a veil that reveals her neck and chest. The skin visible is covered in calligraphy. In other photographs in this series, some women hold rifles and guns.

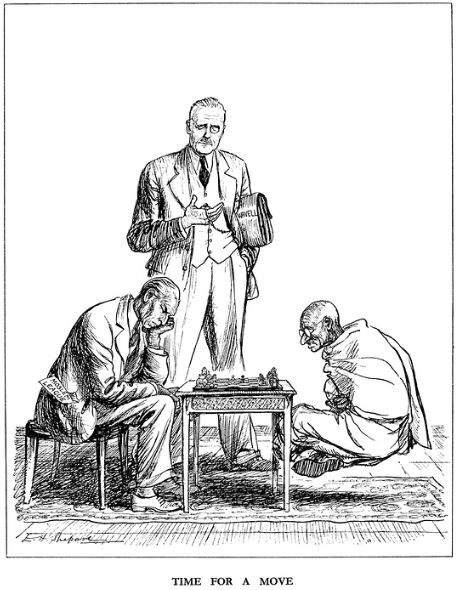

This satirical cartoon illustration from the British Magazine Punch, shows Mahatma

This satirical cartoon illustration from the British Magazine Punch, shows Mahatma

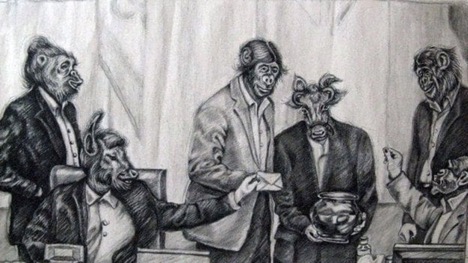

Stevya Mukuzo

Stevya Mukuzo

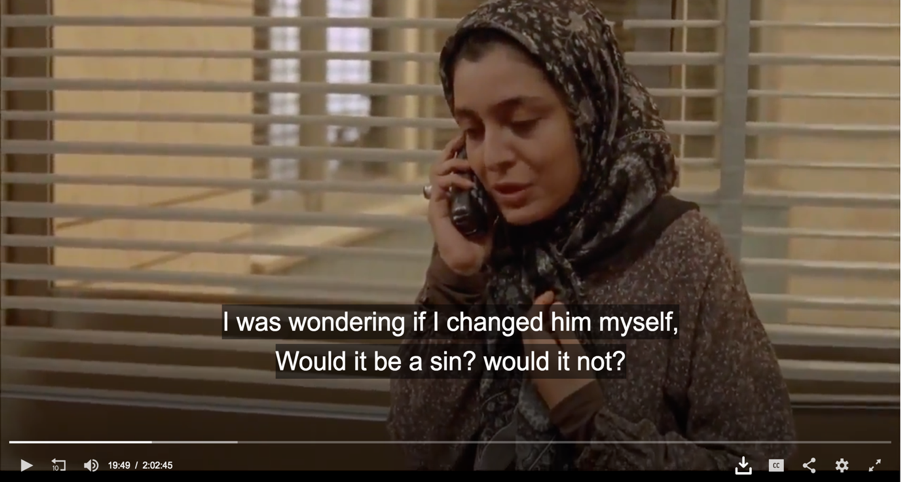

Another example of multiplicity that is drawn from the film is the way the women dress. Looking at the multiplicity that exists within all facets of Iranian life is also apparent in the way the female characters in the film dress. Echoing religion scholar

Another example of multiplicity that is drawn from the film is the way the women dress. Looking at the multiplicity that exists within all facets of Iranian life is also apparent in the way the female characters in the film dress. Echoing religion scholar