In the Iranian film A Separation, the winner of the 84th Annual Academy Award for the Best Foreign Language Film, director Asghar Farhadi takes us through the story of two families with different socio-economic statuses and their conflicting relationships. A Separation embraces an Euro-American interpretative framework that does not perfectly resonate with the Iranian models, however, it does not operate in isolation from them either. Iranian cinema emerges as a hybrid medium as part of modernity. I suggest that it is an inherently apologetic platform because it is built to show its non-Iranian audience the pluralistic approach Iran’s people take to their faith, law, and general way of life. In order to conceptualize the way in which modernity’s effect is presented through the film, it is helpful to both introduce Farhadi as well as have a brief synopsis of the film’s plot.

Asghar Farhadi is a forty-five year old Iranian film director and screenwriter with and education from the University of Tehran and Tarbiat Modares University. He is interested in the social and political tensions in Iran and includes them throughout his films. Almost all his films can be explained as circumstances where the needs of the individual are constantly at odds with the proscriptions of a theocracy and the needs of other individuals. This remains true in his film A Separation, where each character has conflicting views on an objective truth and on the meaning of justice due to their beliefs, class, and disposition (Hamid, 40).

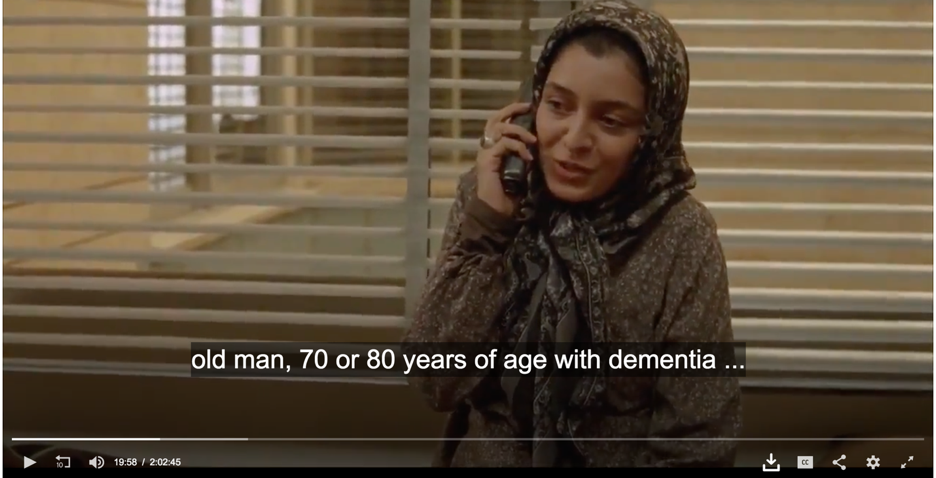

A Separation takes place in present-day Iran and opens with the story of a married middle class couple, Nader and Simin, their eleven year old daughter Termeh, and Nader’s elderly father who suffers with Alzheimer’s disease. Termeh’s mother, Simin wants to move the family out of Iran in order to provide Termeh with better opportunities then what is available to her in Iran. However, Nader refuses to leave his father’s side. This conflict leads Simin to move into her mother’s house and file for divorce as well as custody of Termeh. With Simin out of the house, Nader must find someone to care for his father while he is at work and, on the recommendation of Simin, ends up hiring Razieh, a deeply religious woman from a poor suburb. Razieh took the job without the knowledge of her husband, Hodjat, whose approval according to tradition would have been required. Razieh becomes overwhelmed with the demanding job of caring for Nader’s father, both physically and emotionally, and especially because she is pregnant. Nader’s father could no longer function on his own and had become immobile as well as mute. Therefore, the responsibilities that were expected of Razieh when taking care of Nader’s sick father were tremendous. She was expected to attend to him in the same way a mother would her baby in addition to cooking and cleaning in the home. Removing heavy trash from the apartment required descending about four flights of stairs each time, making the possibility of a fall very likely. As the plot progresses, it is revealed that Razieh has suffered a miscarriage and with her husband file suit against Nader as responsible for the loss of the pregnancy.

In this film, Farhadi intertwines the real-life difficulty of determining any person as purely good or evil by denying the audience the ability to valorize any ideological or religious point of view. Because of this, Farhadi is able to emphasize to his non-Iranian audience the idea that neither class, repression in Iran, nor Islam can fully explain a characters’ motivations, but rather raise awareness of, what he calls, the universal human condition. In an interview, Farhadi explains this tragedy of the human condition by stating, “Whether you are Iranian or not, when you are put into the position of making these difficult choices, you are always haunted by the question of what would have happened had you chosen differently” (Hamid, 42). Further into this interview, Farhadi also describes his understanding of freedom as a contradiction that can create a lot of personal and social difficulty and how that functions as a part of the human condition.

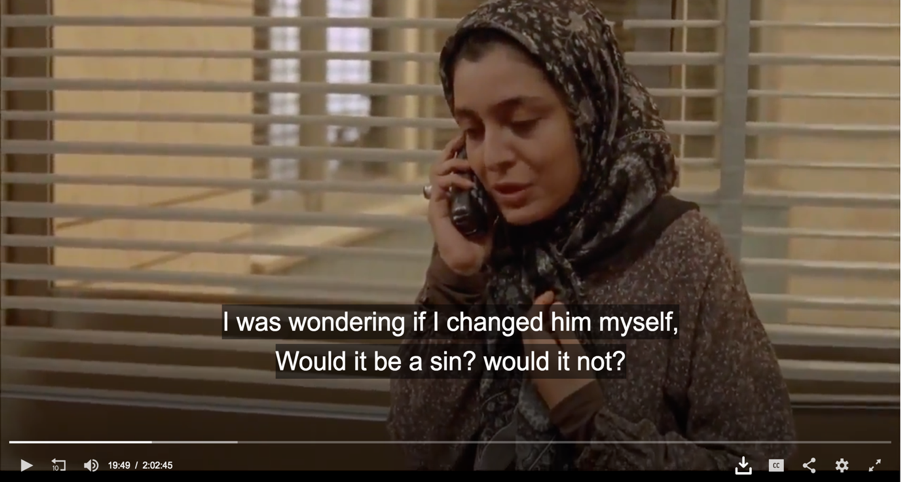

The complexity within each family as well as between both family units is developed in such a way that reflects these “universal truths” (Hamid, 40) in the context of contemporary life in Iran. While religion is absolutely a part everyone’s life in the movie, as can be seen in this scene where Razieh calls someone to consult with them if it would be a sin or not to wash Nader’s elderly and sick father, the pluralistic nature of religious interpretation is also presented.

An example of differing religious interpretation in the film can be seen when Nader calls for Razieh to swear on the Qur’an that her miscarriage was his fault (to which she refuses because she is unsure). In contrast, the actions of Nader such as his stubbornness to admit he knew Razieh was pregnant had more to do with his fear of going to jail than being Muslim. Additionally, Simin’s action to file for divorce also had nothing to do with religious influence but was due to the inter-marriage problem of growing apart from her husband, Nader.

Another example of multiplicity that is drawn from the film is the way the women dress. Looking at the multiplicity that exists within all facets of Iranian life is also apparent in the way the female characters in the film dress. Echoing religion scholar Elizabeth Bucar’s research in her article Pious Fashion, Simin and Razieh in the film dress very differently. Simin, a middle-class woman dresses more urban with a shorter rupush (long coat), a relaxed rusari (head scarf) and jeans, while Razieh, a lower class woman wears a full chador. Bucar’s states:

Another example of multiplicity that is drawn from the film is the way the women dress. Looking at the multiplicity that exists within all facets of Iranian life is also apparent in the way the female characters in the film dress. Echoing religion scholar Elizabeth Bucar’s research in her article Pious Fashion, Simin and Razieh in the film dress very differently. Simin, a middle-class woman dresses more urban with a shorter rupush (long coat), a relaxed rusari (head scarf) and jeans, while Razieh, a lower class woman wears a full chador. Bucar’s states:

The fashionable women asserts her sophistication and design savvy when she successfully incorporates traditional cloth and patterns into a cutting-edge outfit. She is so modern that she takes no risk in wearing village chic—there is no chance that she will be mistaken for an actual villager (Bucar, 39)

Her statement helps to contextualize and understand the differences in women’s dress. With this understanding it becomes clear that the use of clothing as an indicator of socio-economic status is not unique to Iran, but rather a practice that the majority of the world participates in.

The difference and insight to be gained, however, is showing how Islam and the use of clothing to present a certain socio-economic status intersect in such a way that is parallel to Western audiences engagement with the same practice. In other words, Islam does not change the way in which women engage in wearing their socio-economic status, only the kinds of clothing they wear such as a rupush and rusari. Just to push this point further, wealthy Iranian and Western women even buy the same luxury brands such as Gucci, Louie Vuitton, and Chanel.

To better understand how Western critics interpretation of Farhadi, we must first understand what it means for something to be apologetic as well as Faisal Devji’s argument in his essay Apologetic Modernity. While it is hard to give a solid one-line definition of what it means to be apologetic, Devji outlines this concept as a defensive position that the so-called Muslim world has adopted (after being forced into) that stands to prove to the West that Muslims are just like them, or in the context of this paper, Iranians are just like Westerners. Therefore, Iranian film makers use this apologetic position in order to be put on the same international platform and considered for competitions that are mainly dominated by Western cinema and influence.

Devji addresses the “adoption of modernity as an idea among Muslim intellectuals… [and] argues [that] Muslim apologetics created a modernity whose rejection of purity and autonomy permitted it a distinctive conceptual form” (Devji, 61). Devji explains that Muslim debates on modernity are characterized with markers of East and West or Islam and Christianity and have become conceptually central in the Muslim world as well as historically grounded in imperialism because those tended to define the European boundaries of the modern in a peripheral and descriptive way (Devji, 61).

Due to Muslim modernism’s inability to engage and integrate with European though intellectually made Muslim modernism essentially apologetic (Devji, 62). Many Muslim movements separate from film utilize and rely upon this apologetic manner, and while modern Islam scholars have noticed this characteristic they mostly dismiss it as a product of the West’s overwhelming might but are not blind to the negative consequence of determining Muslim apologetic “as a lack and an absence whose positive alternative is naturally provided by the West” ( Devji, 62).

As a director, Farhadi was well received by Western critics on the international scene, who have praised his shift away from presenting Iranians as ‘essentially medieval’ (Rugo, 175). This ‘praise’ unapologetically categorizes all Iranian films produced without the intention of appealing to Western audiences as medieval, but when the film is crafted in an apologetic manner, Western audiences label it modern and find it intriguing. Careful Western film critics, your imperialism is showing.

When examined closely it becomes significantly clear that Farhadi’s work follows a long tradition of Iranian cinema that has both local and cosmopolitan dimensions but differs in its apologetic style. In other words, a tradition that has had a focus on the everyday moral and relational problems of the urban middle-class family and on questions of class identity has not changed, but rather the framework within which it is produced is geared towards a Western audience. Therefore, comparing the framework of Farhadi’s films with Western ones while disregarding all pre-revolution films as irrelevant completely ignores the work of Iranian directors (pre-revolution) as a precursor to Farhadi’s style.

By embracing controversial themes of domestic and social conflict (unlike most post-revolutionary Iranian cinema) Farhadi’s work is seen as a clear break from tradition. Because of this, his work does not perfectly align with the criteria that is commonly used to describe contemporary Iranian cinema, and therefore Western critics look to interpret Farhadi’s films through American and European models. This ultimately led to one critic, Richard Corliss to declare A Separation ‘ready-made for an American remake’ (Rugo, 175). These Western critics support their analysis by emphasizing the presence of American culture in the apartment of the family in A Separation, as well as on Farhadi’s preference for urban settings, relational conflicts, and moral questions that may not have been portrayed in the same way by other Iranian filmmakers.

While I understand these critics’ tendency to do this, I also can’t help but argue that people all over the world who fall into countless categories of identification deal with such issues, and therefore, would be inclined to watch such a movie that they find relatable. American philosopher Stanley Cavell argues that there are a number of thematic parallels between Farhadi’s work and classical Hollywood films, based on the fact that one major theme in A Separation is about the fragility of marriage as revelatory of preoccupations around modernity and skepticism. However, the insistence on proximity between Farhadi and Hollywood overshadows the idea that themes such as different and conflicting moral standings are transnational and not limited to a Western landscape/audience.

The Iranian films preceding 1979 has been deemed irrelevant to post-Revolutionary films completely dismissing the national tradition that existed before and ignoring the origin from which these post 1979 film emerge from. Author of From Iran to Hollywood and Some Place In-Between: Reframing Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema Chris Gow states, “many pre-revolutionary film which serve as precursors to the best examples of Contemporary Iranian film-making are excluded from consideration, simply because they fall out with the restrictive timeline artificially imposed upon the evolution of the New Iranian Cinema” (Rugo, 181). The consequence of ignoring the context from which this post-revolution films were created leads to the assumption that Farhadi is somehow breaking from tradition in addressing themes of broken relationships, human responsibility, and moral dilemmas.

Farhadi’s ability to sway viewers to deeply sympathize with both sides in the film is interpreted as his ability to produce more Western style films, however, I see it more logically as his ability to reach diverse audiences who can all relate to these core universal truths about marriage, divorce, communication etc. Gow notes that the alignment of Iranian cinema with western art cinema has gradually removed and cut off ‘the New Iranian cinema from the particular contests wherein it has developed, but also in which is presently resides’ (Rugo, 181).

In reality, Ebrahim Golestan’s 1964 film Khesht va Ayeneh (Brick and Mirror), among many others are focused on exactly those themes. The new categorization that Western critics call “breaking away from tradition” or Farhadi’s hybrid model seems to be a result of the apologetic manner in which these post-revolutionary films are being created.

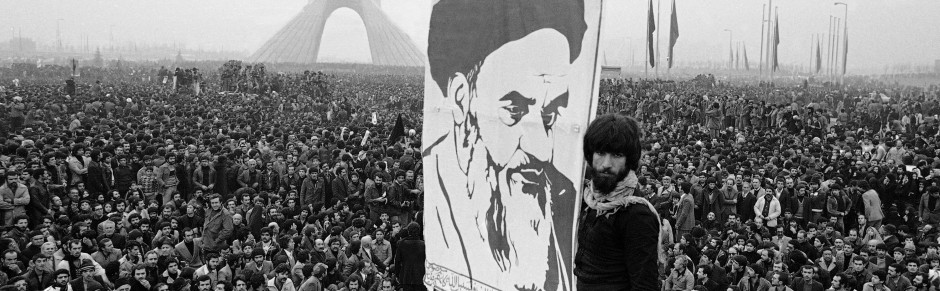

Between the 1950s and 1970s young Iranian film-makers had either studied abroad or had been exposed to well-known Western as well as Indian, Turkish, Russian, and Egyptian directors. This exposure inspired Iranian film-makers to update and revise mainstream cinema, but also to project Iranian daily life through cinematic forms that would put it on the same level as the best works produced by Western cinema. This shift in approach echoes cultural critic Faisal Devji’s argument that Islamic populations formulate their way of life in an apologetic manner in order to appeal to Western populations and as a result are categorized as modern by the West.

Through this framework, Farhadi’s films present Western audiences with pictures and notions of Iran that may be surprising, such as the idea that divorce is an option and an important social phenomenon in a traditional country like Iran. While these factors wont surprise Iranians (in or out of Iran), they have the potential to push Western viewers to question their current perceptions of Iran (Reichle,74). Although religion is something that motivates the actions of Razieh, Farhadi states in an interview that “…for both families, the reasons they do what they do has to do with their material conditions…They are driven by their position in life” (Hamid,41).

The film touches upon issues that are problematic in every society, not just those in Iran’s society. Farhadi addresses crucial questions of social and political relevance in Iranian everyday life while presenting Iran to be a place where families laugh, make jokes, live and work just like anywhere else in the world. Additionally, his characters have problems that are connected to the social and political conditions of Iran, but more than that, their problems are also related to their own actions and emotional or personal shortcomings, further emphasizing the point that people struggle with similar issues regardless of their geographical and religious identity. This effort to show Western viewers that Iran is just like them in order to be put on the same level is as Devji argues, apologetic.

Works Cited

- Farhadi, Asghar dir. A Separation.. Iran and US: Filmiran, Sony Pictures Classic, 2011.

- Rugo, Daniele. “Asghar Farhadi.” Third Text30, no. 3-4 (2016): 173-87. doi:10.1080/09528822.2017.1278876.

- Reza Zabihi; Momene Ghadiri; Abbas Eslami Rasekh. “A Separation, an Ideological Rift in the Iranian Society and Culture: Media, Discourse and Ideology”. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 3, 1, 2015, 105-119.

- Bassiri, Kaveh. “We Live in a Cosmopolitan World.” Film International15, no. 3 (2017): 6-12. doi:10.1386/fiin.15.3.6_1.

- Stern, Fritz. “Freedom and Its Discontents.” Foreign Affairs72, no. 4 (November 18, 2011): 40-42. doi:10.2307/20045719.

- Reichle, Niklaus. “Melodrama and Censorship in Iranian Cinema.” Film International12, no. 3 (2014): 64-76. doi:10.1386/fiin.12.3.64_1.

- Faisal Devji, “Apologetic Modernity,” Modern Intellectual History, 4, 1 (2007), pp. 61–76.

- Cemil Aydin, The Idea of the Muslim World: A Global Intellectual History (Harvard University Press, 2016).

- David Chidester, “Colonialism and Postcolonialism.” Encyclopedia of Religion. Ed. Lindsay Jones. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. 1853-1860. Gale Virtual Reference Library.