David’s Phenology Blog

A fox? A lynx? A coyote?

Posted: February 26th, 2020 by dbattit

I did not know what this was, but upon further inspection it looks like a four-legged critter whose front and back limbs meet on the same side.

Episode 2: Survival

Posted: February 26th, 2020 by dbattit

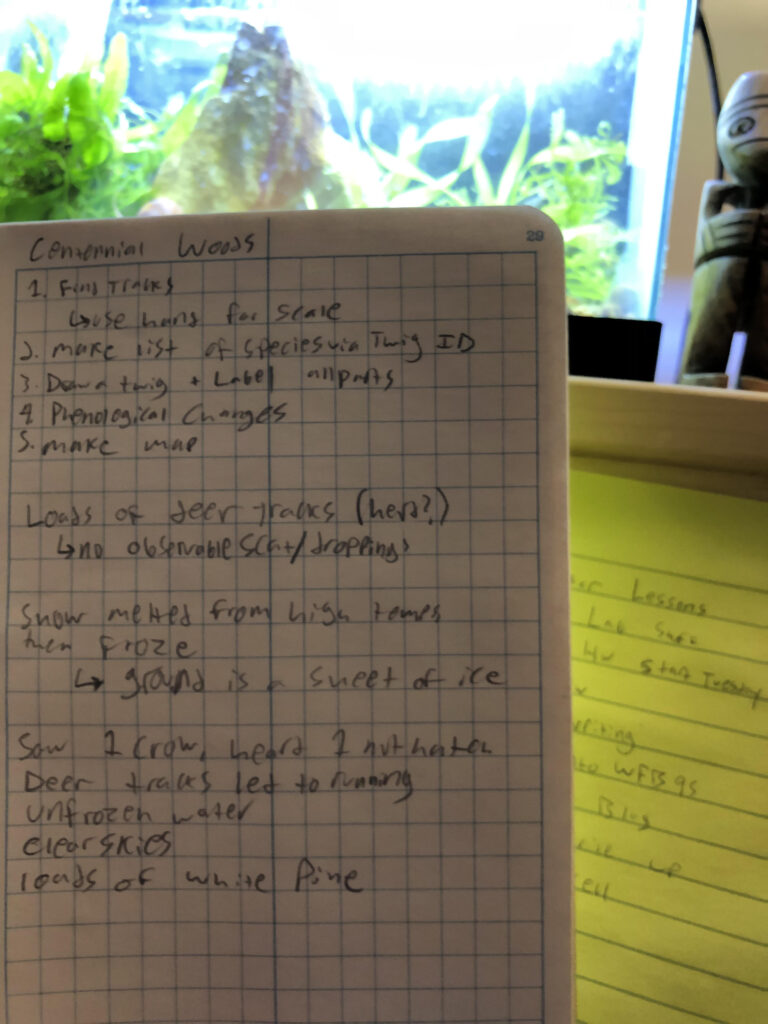

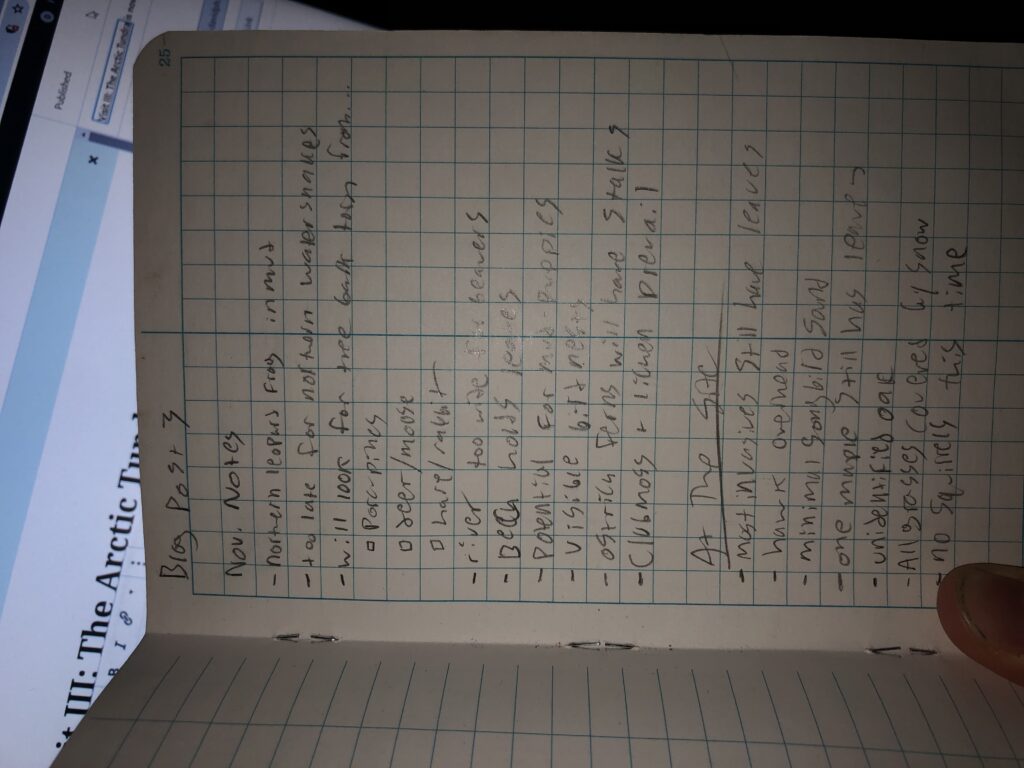

It was exactly 32 degrees out on the day that I returned to Centennial Woods. I was seriously bundled up, with Stayin’ Alive by the Bee Gees powering me through the walk up to the entrance. I entered and again descended the icy backs. Psycho by Post Malone was playing at this point. It’s poppy and overplayed but without a doubt a timeless classic. Unsurprisingly, not much had changed since my last visit. There had been a consistent layer of at least snow if not ice on the forest floor since last I came. The trees lacked their leaves, even some of the beeches. The stream at the base of the hill was rushing due to the warmer temperatures that we had been experiencing in the days prior. Last time it was much slower. I noticed many shrubs and small plants poking up from the accumulated snow. I walked off trail for a bit and could feel the layers of past precipitation in my staggered and crunchy steps. It had just snowed about a centimeter that morning, leaving a fresh dusting to cover up any easily visible tracks. I did my best to push past this limitation despite the great extent that it skewed with my plans to find easily visible squirrel, deer, and rabbit tracks whose interactions I could explain in a basic manner. I’ll do my best to piece together what I observed, but it will not be easy. I saw many strange tracks and a couple other findings related only by the area that they were discovered in. I didn’t see or hear any winged creatures other than the endless flock of local crows. I looked for songbirds little footprints around the bases of trees with seeds and nuts, but the added effects of the new snowfall and the melted slush of yesterday quickly rendered any small imprints on the surface invisible.

As the pictures from my trip depict, I found a strange gruesome strip of what I assume to be deer hair. I recognized the hair from my brief stint in fly tying, although I could be wrong. It had tissue at its base and some blood matted in towards its ends. There were other smaller pieces of hair and miscellaneous deer bits scattered around the area. I don’t know what the heck happened there or how that piece of whatever it was came to end up on the ground. There were no noticeable signs of animal conflict and no signs of the animals themselves. The species that I’ll be focusing on here is the white tail deer (not because it’s a common species, but because I found pieces of one). These deer live in temperate forests but prefer transitional areas where they can spend time in fields and farms but duck into the forest when needed. According to ecosystems.edu, white tailed deer travel many more miles during the night than they do the day. I predict that they move slowly during the day because they know they could be easily spotted. In truth, they will lay down at their bedding area and remain in that general vicinity until dusk. Once nighttime provides them with the cover they need, they can forage and browse the shrub layer of the forest. Gray wolves and mountain lions are the natural predators that keep deer populations in check, but they have been hunted and have been out of the area for decades. Now we are the deer’s predators.

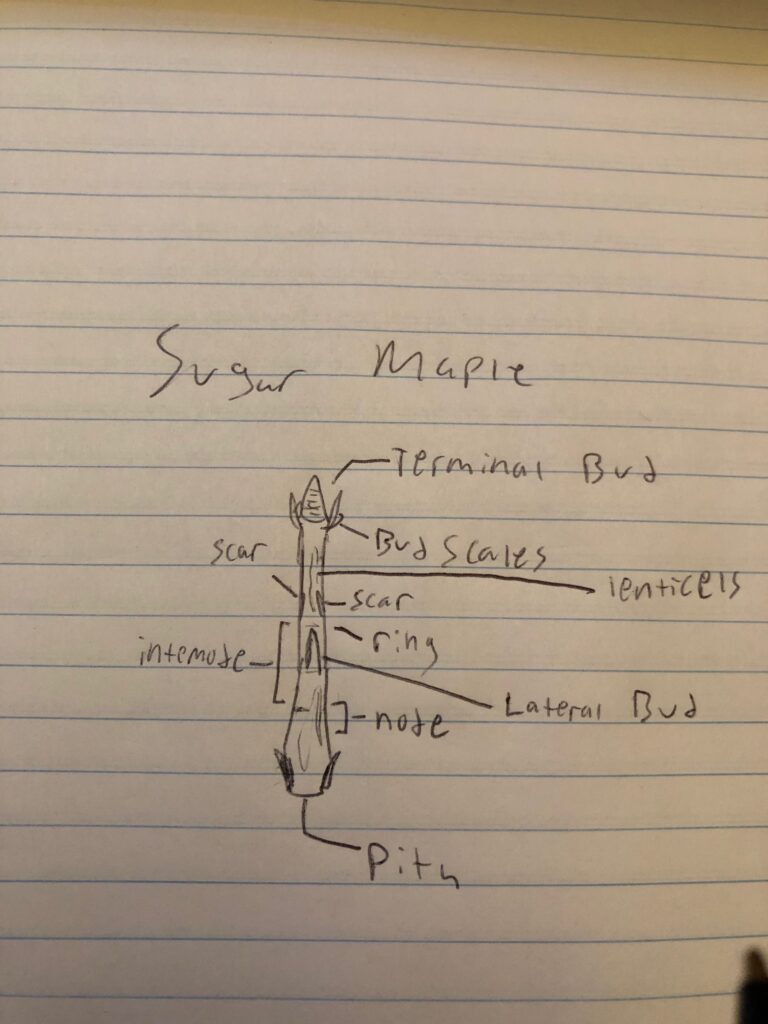

The forest has a healthy population of white pines, whose buds and twigs deer will eat willingly above other pine species. There is also a considerable amount of sugar maple the deer enjoy feasting on. This is a direct interaction between the deer and its food source, where the deer positively benefit from the relationship while the trees are adversely affected. They get their twigs chomped off, meaning there is no new growth on that shoot for the next season. We’ll just call the white pines and sugar maples one organism so that I can write about something more interesting.

This next indirect relationship is a concept that I just learned about today (February 26, 2020) from guest lecturer Michael McDonald in my WFB095 class. I had to look far and wide to find squirrel tracks in Centennial. I didn’t anticipate it being that hard, but at long last I found a faint trail leading into a dense brush where the squirrel presumably found its cache. The relationship that I’m about to describe is between the deer and the squirrel. Deer browse the shrub layer, wandering until they find a patch to focus on and eat with intent. This benefits the shrubs, as their loose spaced out branches get trimmed at the tips of their shoots. This promotes dense re-growth during the next season. If I were a squirrel, I would want my nut cache in a place that is not easily noticeable nor accessible. The squirrel tracks that I found were going right under a dense bush. This bush was an invasive rose bush. Google informed me that deer will eat rose leaves, twigs, and even their thorns. This (could) mean that because the deer fed on the rose, the squirrel was inclined to hide its food there.

I found quite a few tracks that I could not identify. One actually resembled Kevin the snipe’s footprint from up, funnily enough (recall last month’s episode). It had three large toes and resembled a dinosaur or large bird. There were boot prints nearby, so I surmised that it was other people just having fun and making a dino print. I also found tracks of something that made three large imprints. I think it might’ve been a rabbit. It also could have not been a rabbit. It could have been a ground hog too, or maybe not. It could have been a skinwalker creeping out of the shadows to prey on unsuspecting hikers. It also could have not been that. I will never know.

I hope you enjoyed this month’s installment in the Centennial Woods Saga. Be sure to tune in next month, as the plot really thickens once we finish the rising action and explore how the protagonist awakens and discovers their true potential. This realization provides them with the ability to take on the antagonist, who will be introduced at a later date. Stay tuned for Episode 3: Awakening.

When do they sleep? (Deer-Forest Study). (2016, November 24). Retrieved from https://ecosystems.psu.edu/research/projects/deer/news/2016/when-do-they-sleep

January: Endurance

Posted: January 29th, 2020 by dbattit

David Battit

Phenology Blog

Don’t get me wrong, the Salmon Hole is great. I took a walk there to go fishing on my birthday back in September and caught a decent smallmouth bass. The ecosystem is wonderful, and I saw loads of fish. The mammals and other wildlife on the land are scarce though, and the spot is littered with, well, litter. It’s a small parcel of land in the midst of a major roadway, and it’s simply depressing how dirty and inhospitable that those poor couple of acres are. It is for this reason that I am OFFICIALLY RELOCATING my phenology site to one much quieter, cleaner, and frankly more interesting. Centennial Woods Natural Area, you better be ready because here I come.

I live in McAuley Hall on Trinity campus. The walk to the Salmon Hole was an easy one, right down the hill into Winooski. (The walk back wasn’t quite as easy). Fortunately, East Ave serves as the highway to my new phenology site where my spirit can experience nature and positive energy surrounded by beauty, man. It is located only a couple hundred feet from McAuley Hall, and after a ten minute walk up the street you bank a hard left and find yourself at the pearly leaf-shrouded gates of Centennial woods, the home of the first natural resources lab.

It was about 15 degrees out upon my visit to the woods. I air-drummed to Neil Peart’s solo after the bridge in Rush’s Tom Sawyer as I descended the icy banks into the forest. My headphones died from the cold before I could slip and fall, which was probably fortunate considering the treacherous terrain ahead. There were deer tracks all over the place, melted and disfigured from the fluctuating temperatures of recent days. I scoured the trees for twigs to get the identification points required for full credit. The species I came across were sugar maple, white oak, basswood, white birch, and then white pine, which had no twigs because of its coniferous superiority to winter. I cannot compare the phenological changes in Centennial Woods to those of the Salmon Hole because they are two different locations with different features. This is okay though, because I try to go for a hike in Centennial every once and awhile. The seclusion, silence, and connectivity offered by being surrounded by trees is an excellent incentive to escape the noisy characteristics of the city. Regardless, I have seen much change in the forest in the past couple months. The deer trails that were once hidden in barberry are now open and windswept. The sound of the wind itself changed as there were no leaves to hinder it from passing through. I didn’t see any squirrels, and I thought that maybe their nut caches had frozen shut. I followed a set of deer tracks down a trail, and they led me to a brook with running water. This led me to believe that the deer had been foraging and decided to take a drink from the stream. I got to the bank and saw another set of tracks. These were left by what I believe to be a turkey, but it could also have been a snipe due to its three-toed anatomy (recall Kevin the snipe from Pixar’s UP). The tracks exited the stream bed and then quickly turned back down into it, leaving me with only about 10 feet of tracks. They were interesting nonetheless. The pictures from this trip can be found by scrolling up. Enjoy,

David Battit

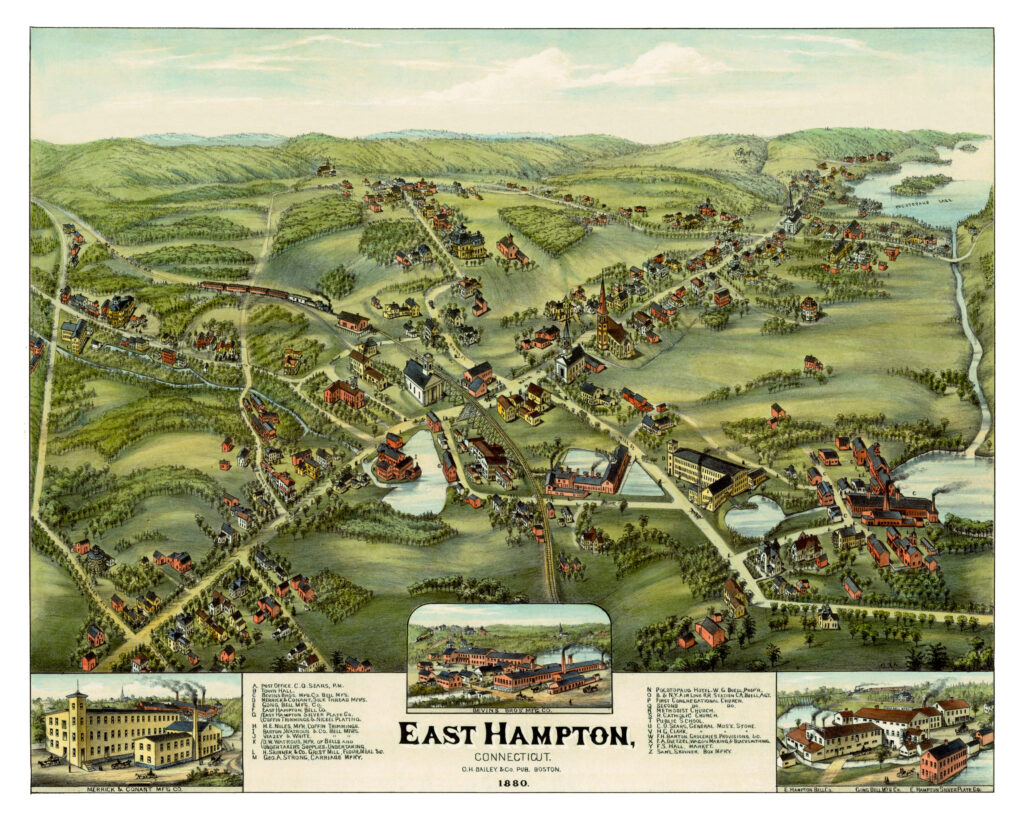

Sense of Place in my Hometown

Posted: December 1st, 2019 by dbattit

East Hampton Connecticut is a small rural town with about 13,000 people. It is home to the second largest natural lake in CT, Lake Pocatapaug. As the towns population has grown, more and more people have moved into houses around the lake, crowding the waterfront to the extent that there is very little natural shoreline remaining that isn’t developed. All of the runoff from these landowners’ fertilizers for their lawns cause extreme blue-green algae blooms in the lake, staining it a rather appealing vomit green for the duration of the warmer months. The town borders Portland, which is the gateway to a small city called Middletown. I always felt that the different towns had different feelings (senses of place). Middletown was obviously quite city-like, while Portland was developed and busy, but with a couple more trees. East Hampton is a happy medium, with a busy-enough town center and the outskirts enveloped by forests. East Haddam is the next town over, and it follows the same trend. That town is largely forested, with fewer developments than East Hampton. I use the forested areas near my neighborhood as a way to connect with nature. This is largely placebo though, as you can’t go more than a few acres without hitting a paved road or house. The biological part of the area is nice, but its physical counterpart kind of ruins the feeling of being in true wilderness for me.

I mentioned the human interactions with the land around the lake earlier in this writing. In the land surrounding my house though, there is another story. The land used to be entirely farmland, with stone walls dividing miscellaneous parcels of land into neat squares. These boundaries have no real meaning anymore, except now I can tell where my property ends and my neighbors’ begins. What used to be cropland is now secondary growth, with a few ancient oaks standing sentry far above the smaller maple-composed canopy. These monarchs are the survivors of a previous climax forest that was felled and tilled into land suitable for farming. It is near these trees that I feel in touch with natural history.

My sense of place has changed between my 17 years of living in Connecticut and the 3 months that I’ve spent at UVM. Vermont contains many more wild lands than Connecticut, and I almost view these natural areas as more pure. Litter is less frequent, the sounds of bustling humanity grow distant as the hills roll into mountains, and far fewer invasive vines strangle the trees until they become ugly scraggly protrusions from the ground. These vines fester through the trees in CT, and the forest aesthetic is a lot less enjoyable. I used to try to hold East Hampton to such a high standard for its forests and lack of industrialization, but coming back home for Thanksgiving made me realize that much of that notion is purely in my head, and the town is really far more city-like than I really care for. I am aware that this doesn’t make me sound good, but I just prefer to be in more sparse and secluded areas than busier ones.

Recent Comments