http://youtu.be/zNgHshuRlpI

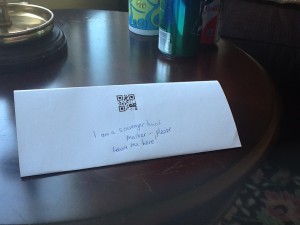

A scene from the great QR code theft, featuring our lead QA tester. Btw, Lucy Wu is the title character of The Great Wall of Lucy Wu, one of the DCF books this year and a clue in the game.

Well so far we’ve only lost 1.5 QR codes and a table. One disappeared mysteriously from on top of a vending machine and had to be replaced on the fly, and the other I managed to talk the dining room staff out of believing was simply brightly colored garbage.

Well so far we’ve only lost 1.5 QR codes and a table. One disappeared mysteriously from on top of a vending machine and had to be replaced on the fly, and the other I managed to talk the dining room staff out of believing was simply brightly colored garbage.

Folded into a free-standing table tent. Anchored by a rock, with a logo.

Note to self: next time label all the QR codes in big letters I AM A SCAVENGER HUNT PIECE. PLEASE LEAVE ME HERE.

Also our table? I set up our tri-fold display and how-to-play sheets on a lobby table, went to the restroom, and returned to find my table snaked and my display on the floor, replaced by someone else’s display. DIRTY POOL, LIBRARIANS.

Other than that it’s gone well.

As this is the third ARIS game we’ve launched at a statewide conference, and the second time we’ve encountered both low numbers of players and QR codes being removed by conference staff, I am going out on a limb here when I say we’re not going to be doing further game launches at conferences.

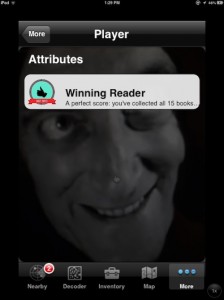

It’s not quite Credly badge integration (the attribute doesn’t link out to the live site) but after much wrangling, it works: you answer questions about 15 books, win the game and get the Winning Reader badge.

It’s not quite Credly badge integration (the attribute doesn’t link out to the live site) but after much wrangling, it works: you answer questions about 15 books, win the game and get the Winning Reader badge.

There’s got to be a way to automatically award the badge via Credly, though. I wonder if we could get hold of their API?

Next week, my nascent group of Burlington-area ARIS developers will be meeting to begin work on the construction of “DCF Book Run”, a game in which players will complete up to thirty mini-challenges to demonstrate that they've read the thirty books on this year's Dorothy Canfield Fisher (DCF) Award list. The game will make its very public debut at the DCF Awards on May 3rd, where we'll open it up to Vermont's librarians.

The basic game-play mechanism will be relatively simple: players will wander the awards campus location looking for QR codes accompanied by the cover of each DCF book. When the QR code is scanned from within ARIS, the game will present the player with a challenge related to the content of the book. Players can level up in the game based on the number of correct answers they provide. So the goals are iterative: solve a mini-puzzle based on each book, and solve enough mini-puzzles to advance through the levels (Bookworm > Reading Rockstar > Head Librarian) until all 30 books are completed.

While the game will debut at a conference for librarians, the target game-playing audience are middle schoolers, in grades 6-8, and those are the standards we'll be targeting. One of the intended outcomes of the game is for the librarians to deploy this game at their own schools and encourage students in grades 6 through 12 to play and to get interested in creating on the ARIS platform; ARIS would be difficult to learn to build in for the majority of students younger than 6th graders, but older students should be able to extrapolate what their own age-appropriate games could look like.

In-game challenges will take several forms:

Another intended outcome of this game is that it correspond to the qualities I outlined in constructing my own games rubric, as explained below.

1. Design Quality

This will probably be the hardest aspect to execute well, so I'm going to depend heavily on the Organization and Design section of this rubric, namely that “There are multiple graphic elements and variation in layout” (challenge objects will be presented in a combination of images, text, close-captioned audio and video) and “Design elements assist students in understanding concepts and ideas” (by including the covers of the books both with the QR codes and attached to each reward for solving a challenge).

2. Feedback

As soon as a player has answered a challenge correctly or appropriately, a virtual book object will be added to their Inventory. ARIS provides a mechanism at the editor level to customize an error message for each challenge. As I do recognize the limitations of providing only one unchanging error message, we will also be implementing:

3. A Hinting System

A character the player can ask for hints on how to solve each challenge. The character we've chosen is the ghost of Dorothy Canfield Fisher, and the question process will look like this screen from Mentira:

Players will be able to locate the hinting ghost from any area of the game and at any time, via the Nearby tab. This still from The EpiQRious Caterpillar demonstrates a similar concept; players could re-read How To Play at any time and in any game location via Nearby.

4. Collaborative Accessibility (A Social Aspect)

Players will have the ability to leave other players or the game designers themselves feedback by submitting a text, audio or video Note. Notes are pinned to the in-game Map, and you can read and comment on other players' Notes. Contributing n Notes will be a requirement of the DCF game, and commenting other players' Notes will earn the commenter badges they can display on their in-game profile.

5. Ties to Common Core

The content we use to draft the questions and challenges will come from multiple curriculum areas and all tie back to one or more Common Core standard for grades 6-8. For instance, one of the books on this year's list is Joan Bauer's Close to Famous. It's a book about cooking, so we could build some math questions based on a presented recipe.

Another book on the list is The Great Wall of Lucy Wu, by Wendy Wan-Long Shang, about how a Chinese-American middle schooler tries to relate to the experiences of her elderly Chinese great-aunt, including how their family was affected by the Cultural Revolution. Details about the Cultural Revolution are included in the book, and can form the basis for questions that meet this criteria.

The inclusion of hangman as an activity meets this criteria.

The driving idea behind the game, that of students demonstrating that they've read and understood books appropriate for their grade range, meets this criteria.

6. Enjoyability

This is the hardest aspect for a developer to accurately assess. In fact I would argue that it's impossible for a developer to determine how enjoyable their game is. And that's why we're aiming to have a prototype of the game ready to be tested by classes of middle schoolers whose teachers are interested enough in examining ARIS in the classroom to let us invade. We'll ask the students to play our game and provide a supportive space for them to give us their vocal feedback as well as encouraging those less comfortable with public feedback to leave us a Note on the in-game Map.

Moving forward, one of the ways we'll be gauging the effectiveness of our game is by invading more middle school classrooms and having some portion of the students play the game, and another portion of the students simply answer the questions about the books via the traditional seated pen-and-paper method, and a third portion of students answer the questions via an online but seated interface. However, one method of effectiveness that we're extremely interested in gauging is:

7. Reproducibility

It's important for us to model ARIS' open source nature so that students who are interested in building their own games understand that ARIS was created for that reason, and that there's an active and student-friendly group of developers in Vermont who can't wait to hand the reins over to the next generation of gamers.

you can take it too:

It’s a month long, run entirely online via Badgestack, and the next sections are April 1 – 26, 2013 and July 8 – August 2, 2013. It’s primarily designed for folks with teaching credentials, but I made my way through nonetheless, and I can’t wait to put my newfound knowledge to use.

I’m really taken with this educational games evaluation rubric from Sacramento State, not only because it helped me specify a lot of my thinking about what makes a great game, but because I think it’s well-crafted as an online tool teachers could use to quickly score a video game for potential use in their classrooms. From this rubric, I distilled the following seven personal criteria:

1. Design Quality (an amalgam of the 3 Instructional Design and Delivery criteria): Students consume more and better games than I can dream of, and I want them to be captivated by the quality of the presentation in a way that translates to “the design does not interfere with the player’s desire to progress toward the goal — in either a bad way or good”. Clearly stated directions for gameplay; graphics that don’t cause students to die of mocking laughter but also don’t stun them into silent, still contemplation of each scene; transparent in-game navigation; a compelling reward for game completion.

2. Feedback: students should be able to ascertain whether they have executed an in-game challenge to an acceptable level with immediate, unambiguous feedback. Not knowing whether you’ve done a thing correctly deters player interest and progression.

3. A Hinting System: asking for help should always be an option and never, ever be penalized. It’s a fundamental life skill and I judge hidden object games which dock you points for using the hint button very, very harshly.

4. Collaborative Accessibility (A Social Aspect): in ARIS, as a player, you nearly always have the ability to leave other players or the game designers themselves feedback on the game by submitting a text, audio or video note. You can read and comment on other players’ notes. Sometimes this is a required element to either complete the game or earn an in-game badge. I like that this system encourages student voice and collaboration. I would score this via the Interaction table of the CSUS rubric.

5. Ties to Common Core: As McGonigal repeatedly points out, games have a great deal of potential for real-world applicability, and in a classroom I would want something concrete I could tie this to. So if I’m giving a student a hidden object game, I want to be able to point out that it adequately addresses Vermont Common Core Standard 2.e, appropriate word use. Or that I’ve chosen one particular hidden object game because it makes players search for three bows in one scene: a ribbon, an archery implement and a cello accessory (VT 4.1.g).

6. Enjoyability: because if it’s not fun, students won’t be motivated to do it.

7. Reproducibility: one of the most powerful ideas games can present is the challenge to a player to improve upon the original. Whether it’s a D&D sourcebook, which gives players one map of a forest (of doom) and encourages them to write/speak many paths through it, or Viqua Games Build Your Own Hidden Object platform, a really superlative game inspires you to create. Games built on open-source or reproducible platforms provide a means for students to harness their enthusiasm and creative energy in building better games. Or in gamerspeak, “p0wning” the previous generation.

I confess, I’ve been hunting and evaluating hidden object games for literacy purposes for nearly a year now, so I’m kind of coming at this from a skewed background. But having played nearly a dozen hidden object games to their conclusions with this growing awareness of literacy needs in mind, I’m starting to put together a list of hidden object games I think are particularly worthwhile*.

One game I’m particularly enamored of is Sea Legends: Phantasmal Light. It’s the story of a couple who are shipwrecked on an island by a freak storm, and one half of the couple awakens just in time to see — or think she sees — her boyfriend being kidnapped.

Determined to rescue him, she sets off to explore the island, solving puzzles and hidden object scenes along the way. But these activities are all in aid of her rescuing the boyfriend and simultaneously determining whether the lighthouse on the island is haunted.

It’s a hidden object game: you explore a landscape, drill down into smaller sections of the landscape to find tools you need for tasks and solve a bigger puzzle. It’s self-paced and non-competitive; the flip side of that is that it’s non-collaborative.

The only rule I’d modify if using this with students is to come to some agreement with them as to whether they want to play with standard hint availability (refreshes on a 60-second clock), challenge hint availability (refreshes on a 2-minute clock) or with no hints. These games really strike me as a way for individual students to work on their literacy and vocabulary skills rather than as in-class collaborative exercises. But as one 5th grade teacher commented, they’re exactly right for taking the stigma out of being a student aged for one grade level with the literacy or English skills of someone much younger.

Why do I like this particular game so much? For one over-riding reason: you’re not going to win if you don’t puzzle through the diary entries, gravestone epitaphs, newspaper clippings and instructional sheets that provide information for you to solve the main mystery.

For instance, this.

Also, I haven’t found any of spelling and semantics problems; items in locations make sense as to why they’d be there (why is there a cat in this nest of owlets? And a jack-in-the-box?) and are spelled correctly and in accord with US English (there’s no such thing as a candle-sniffer, Enigmatis. I looked it up to make sure.)

Sea Legends has the potential to be more than a straight-forward vocabulary testing tool. I found the story to be compelling, and appreciated the gender politics at play. I could see asking the student to summarize the story via a written or oral assignment, and I’d feel comfortable assigning it as work the student could feel comfortable playing with the support of his/her family.

Now I just have to figure out how to clone it.

*Still looking for a blog that evaluates them in literacy terms.

ELL students and others who struggle with reading issues feature an uphill battle for skill mastery that’s compounded by the social stigma and real-world functional problem that language deficits present. While they’re trying to learn from textbooks they’re also missing out on social interactions that a) could otherwise bootstrap their skills and b) put them at higher risk for bullying behavior.

Enter the hidden object game.

In hidden object games, players have two concomitant tasks. The overarching point of the game is to solve a specific mystery: rescue a companion, retrieve a MacGuffin, solve a missing persons case. And in order to solve the mystery, they search the game-world for useful items, mostly by drilling down into magnified portions of scenes and clicking or tapping on the visual representation of items from a list of words.

While you as the player can’t change which words are presented, in quite a few games you can change how frequently the game will give you hints or whether there are no hints at all.

Assessing a player’s skill improvement with any given hidden object game could be achieved via pre- and post-testing with a simple vocabulary matching sheet. Depending on the age and skill-level of the player, it could be: having to write the name of each object next to its picture; drawing lines from picture to vocabulary item; or asking the learner to write out a definition for each term.

The storytelling qualities of hidden object games lend themselves to content-based quizzes and written reports, where teachers could ask the students to summarize the story so far, or answer questions based on the locations they’ve already visited.

Additionally, because the player’s goal is to move through a landscape in a journey-like fashion, another assessment possibility would be to have the player create a map of where they’ve been, describing the landscape and a few sentences about each location.

Both the written reports and the map creation could be done formatively, so the teacher obtains an idea of how well the student is progressing as they play.