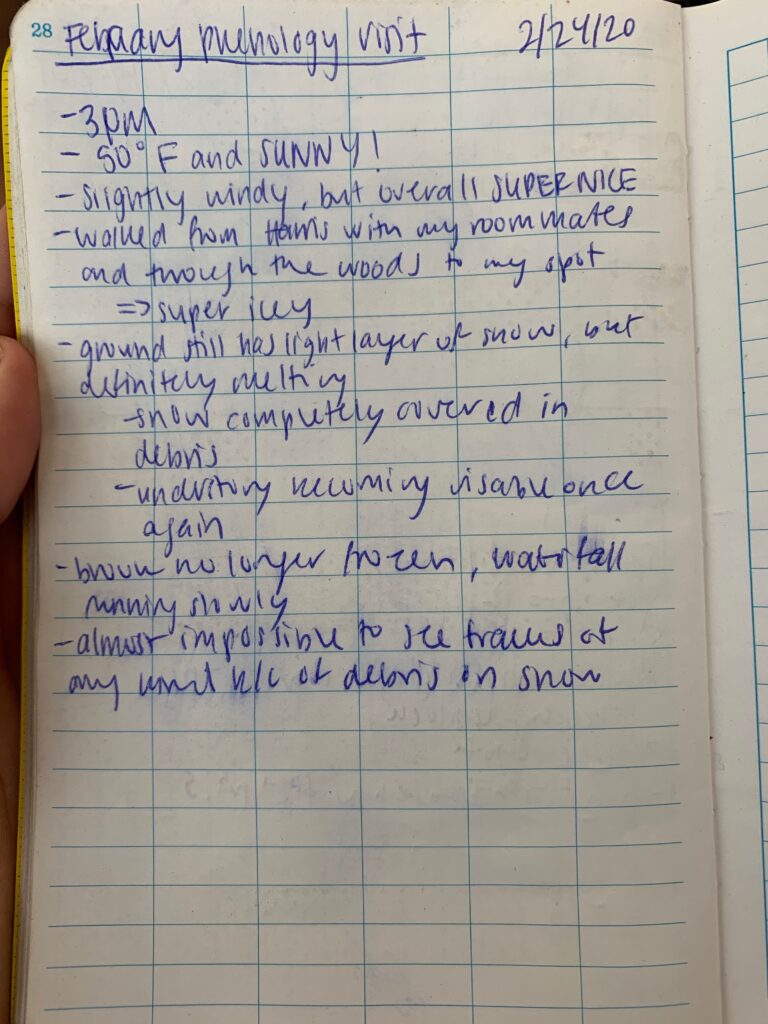

Today, February 24, was a beautiful spring day in Centennial. It was a balmy 50º and sunny around 4 PM. The warm temperatures melted the majority of the snow from my last visit. The ground was extremely icy along the path and the rest of the snow was covered in small debris from the trees which made seeing animal tracks almost impossible. The brook was also running and was mostly unfrozen. The deciduous trees still don’t have any leaves.

The main evidence of wildlife present was two small pieces of scat I found. They were very small and circular, and seemingly old because they were melted into the snow. Because of their size and shape, which could’ve been warped by the melting snow, I’m guessing that it was eastern cottontail scat (Levine, L., & Mitchell, M., 2008). However, I would expect eastern cottontails to produce more scat, so I’m guessing that the other pieces may be buried deeper in the snow or completely disintegrated into the melt.

During the winter, eastern cottontails either use burrows dug by other animals or huddle under vegetation (Kiley, 2019). Eastern cottontails also breed from February to September, so it is possible that this cottontail is getting ready for the breeding season or has already started breeding (Kiley, 2019). Eastern cottontails are herbivores and scavenge for plant material. However, when there is none left during the peak of winter, they survive off of the bark of woody plants (Kiley, 2019). Cottontails are mostly nocturnal, but they sometimes come out in early morning and dusk to eat (NHPBS). Its main predators are coyotes, foxes, weasels, eagles, and hawks, and in areas close to human development, even cats and dogs (NHPBS).

While the debris cover made it very difficult to identify any other clues in the landscape of the cottontail, I did find it near visible woody understory which it may have been feeding on. The majority of the organic material on the snow was pine needles which isn’t a part of a cottontail diet, but there were some smaller branches and twigs which appeared to be deciduous that I struggled to identify which it most likely fed on.

I also found some dog tracks in the snow nearby, so it is possible that on an early morning, or dusk time walk, the cottontail heard and smelled the dog, and quickly hopped away. Since eastern cottontails are preyed on by dogs, their senses are finely tuned to detect danger. While the cottontail was feeding and then pooping, it most likely heard the dog from far away and hopped away in fear to its burrow or a hidden area.

References

Kiley. (2019, January 28). How cottontail rabbits survive the winter. Retrieved from https://dickinsoncountyconservationboard.com/2019/01/28/how-cottontail-rabbits-survive-the-winter/

Levine, L., & Mitchell, M. (2008). Mammal tracks and scat: life-size tracking guide. East Dummerston, VT: Heartwood Press.McDonald, M. (2020).

McDonald, M. (2020).

NHPBS. (n.d.). Eastern Cottontail – Sylvilagus floridanus. Retrieved from https://nhpbs.org/natureworks/easterncottontail.htm