Juan P. Alvez | Pasture Technical Coordinator, Center for Sustainable Agriculture – UVM Extension

One of the questions grazing farmers often ask are, what type of forages will grow well on their farms or, which will best suit their livestock? It’s probably no surprise that the simple answer is “lots of them!” as oppose to one or two annuals. Thus, most grazing farmers should aim for as much forage diversity as possible, trying different arrangements and combinations. When several species are present, the diversity and competition among them will build pasture’s resiliency. Different species will be able to thrive under different conditions and animals will be better able to withstand unexpected events such as an extended drought, or heavier than normal rains. In general, the highest benefits come from perennial species, because they are able to re-grow after being sheared by a machine or grazed by animals. When well-managed, perennial pastures can and will yield excellent production. To set up your pasture rotation you can start with this pasture worksheet based on Bill Murphy’s research and prepared by Lisa McCrory). In general, the greater the variety of perennial pastures, the better the nutrition that will last along the growing season, helping diversify your herd’s diet without significantly increasing costs.

Benefits of well-managed perennial pastures

An unturned perennial pasture sod will not only feed livestock through forage that will be further converted to dairy, meat or wool, but also provides many valuable ecosystem services, including: erosion control, nutrient cycling, soil formation, carbon sequestration and sink, prevent nutrient runoff, catch soil sediments and water quality.

What species to use?

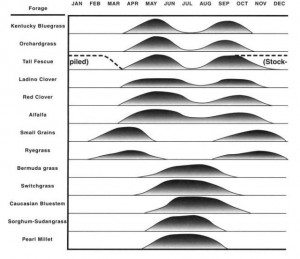

An ideal forage pasture sward should include three main categories: grasses, legumes, and forbs. In general, legumes provide proteins, (which are the building blocks for animal growth), and increase total digestible nutrients (TDN). Grasses mostly deliver energy via carbohydrates (sugars). Forbs (some known as weeds), provide vitamins and vital compounds. Be careful with poisonous plants animals might not be aware. Establishing forage species can be as simple as broadcasting them in a pasture strip (by hand or with machinery) just before animals are to be moved to a new strip or pasture. That way, animals can briefly walk around the strip or paddock to promote seed-soil contact and stimulate better germination. Remember that legumes need some special preparation (i.e.: inoculation) for maximum benefit (see next post, and check this factsheet). Annual or biennial forage species can provide feed supplementation for grazing animals in times when some perennial pastures decline production. A practice that can be adopted is deferring or reserving sections of perennial pastures for later in the season and take advantage of the bulk energy and nutrition provided by annual forage species. In general, in the Northeast, annuals are best provided during mid to late-Summer, to help overcome dry spells and during Fall, to extend the grazing season (see Fig. 1 and previous post).

Figure 1. Common NE forage species growth chart. Click image to enlarge. (Forage growth chart by Virginia Tech University)

Common forage species for the Northeast

Annual, warm season forage species that work well in the Northeast are pearl millet, Sudangrass and Sorgum. Brassicas can be also added to the mix. Annuals can be seeded down around mid-June –weather permitting-, and grazed or cut 30 to 45 days later, providing bulk feed (sometimes two cuts) in times when not much forage is available. At the same time, this practice could provide a breather or further rest to existing perennial pastures which, may need extra time to fully recover for the last grazing in the Fall. Fall annual grain forage crops like, triticale, oats barley and wheat can provide grain and grazing purposes. For more information about annuals in the Northeast, please visit UVM NW Crop and Soils Program.

Cool season recommended forage species are: timothy, orchardgrass, brome, festulolium, rye grass, tall and meadow fescue (Table 1). An important reminder about tall fescue: Tall fescue can be infected with an endophyte fungus that will release an alkaloid that would protect the plant. However, it may cause animals’ to suffer fescue toxicosis making them susceptible to heat stress. Heat stress will cause animals to find a cool spot in the paddock (e.g.: shade, pond) reducing their grazing intake and producing less. To minimize this, you may not want to give your animals just fescue but, a good mix of forages. A great deal of information on species characteristics, management and adaptation can be found at UVM Crops and Soils page.

Table 1: List of some common forage species suitable for the Northeast.

| Grasses | Timothy (Phleum pratense) | Tall Fescue (Festuca sativae) | Rye Grass (Lolium repens) | Brome (Bromus inermis) | Reed Canary (phalaris arundinacea) | Festulolium |

| Legumes | White clover (Trifolium repens) | Red Clover (Trifolium vulgaris) | Alfalfa (Medicago sativae) | Birdsfoot Trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) | Vetch (Vicia) | Alsike Clover (Trifolium hybridum) |

| Forbs | Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) | Plantain (Plantago major L.) | Buckhorn Plantain, Plantago lanceolata L.) | Bull Thisle (Cirsium vulgare) | Milk weed (Asclepias) |

The take-away messages?

- Carefully walk and observe pastures and practice dynamic management under rotation, as needed;

- Go perennial, go diverse. Encourage perennial pastures because they provide the most valuable resources and only need sunshine, water, nutrients and adequate rest after being grazed or machine cut;

- Inoculate your legumes;

- Avoid plowing.

Have you explored different successful forage ideas? You can share them dropping us a line at the UVM Pasture Program:

Juan Alvez (jalvez@uvm.edu); Kimberly Hagen (kimberly.hagen@uvm.edu) and, Jennifer Colby (jcolby@uvm.edu)

Recent Comments