They’re calling him “Nairon-Man” and “King-tana.” This past Sunday, Nairo Quintana won the Giro d’Italia, which makes him not only the first Latin American to win this prestigious bike race, but only one of six who have won it their very first time riding it. He is currently ranked by the UCI as the world’s #1 rider (though that’s likely to change after the Tour de France next month, which Quintana will not participate in). As if this news weren’t good enough, the second place finisher was also a Colombian, Rigoberto Urán, and the winner of the “King of the Mountain” award was also a Colombian, Julián Arredondo. Declaring it a “historic day,” newspapers, television stations, even the president have celebrated this victory as Colombia’s most significant accomplishment ever in its sporting history. With these victories bicycles are on people’s minds here in Colombia.

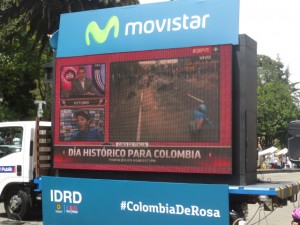

Because Quintana’s victory was more or less sewn up before the race actually ended, Sunday morning Bogotá’s institute of sports and recreation (along with Quintana’s team sponsor, Movistar) set up a large television screen on Avenida Séptima to show the end of the race, so that people on bikes participating in Ciclovía would not have to miss it. I spent about a half-hour there watching the awards ceremony after the end of the race with a crowd of some sixty or so cyclists of all stripes–men on racing bikes in full team kit, kids on training wheels being pulled by a rope by a parent, young women on mountain bikes, and so forth–in other words, the typical mix of people young and old, male and female out for a recreational ride who you’ll see in Ciclovía (but won’t see during the week riding for transportation).

Because Quintana’s victory was more or less sewn up before the race actually ended, Sunday morning Bogotá’s institute of sports and recreation (along with Quintana’s team sponsor, Movistar) set up a large television screen on Avenida Séptima to show the end of the race, so that people on bikes participating in Ciclovía would not have to miss it. I spent about a half-hour there watching the awards ceremony after the end of the race with a crowd of some sixty or so cyclists of all stripes–men on racing bikes in full team kit, kids on training wheels being pulled by a rope by a parent, young women on mountain bikes, and so forth–in other words, the typical mix of people young and old, male and female out for a recreational ride who you’ll see in Ciclovía (but won’t see during the week riding for transportation).

Though people in the crowd didn’t tend to stay long (they were, after all, out for a bike ride), I did have a chance to talk to a few people and it was clear to me that a number of them had been following the race not just here at the end but since its beginning in early May and that they had a sense of the race’s details. They also said they were proud of Quintana’s victory and how well the other Colombians did. People erupted in cheers whenever they showed one of the Colombian’s receiving an award. A few people waved Colombian flags they had with them for the occasion.

It was a pretty mild response, though, and in some respects this isn’t so surprising. Colombians are not especially nationalistic and their strongest expressions of nationalism, with a few exceptions (such as territorial conflicts with neighbors), are often associated with how well their national sports figures are doing–in European professional soccer, the Olympics, and especially the World Cup. Colombians also tend to be strongly regionalistic, which moderates their sense of identification with the larger sense of nationhood. Here in Bogotá, people tend to identify as either “cachacos” (an image of a polite and cultured city dweller) or as residents of a cosmopolitan melting pot. They don’t think of themselves as “regionalists;” they’re “capitalinos” (residents of the capital).

It was a pretty mild response, though, and in some respects this isn’t so surprising. Colombians are not especially nationalistic and their strongest expressions of nationalism, with a few exceptions (such as territorial conflicts with neighbors), are often associated with how well their national sports figures are doing–in European professional soccer, the Olympics, and especially the World Cup. Colombians also tend to be strongly regionalistic, which moderates their sense of identification with the larger sense of nationhood. Here in Bogotá, people tend to identify as either “cachacos” (an image of a polite and cultured city dweller) or as residents of a cosmopolitan melting pot. They don’t think of themselves as “regionalists;” they’re “capitalinos” (residents of the capital).

In line with that sense of regional identity, the strongest outpouring of public pride in the victory came from Quintana’s home department of Boyacá where, as a friend of mine who was there over the weekend told me, there was a widespread party-like atmopshere.

And yet it is true that another source of nationalistic identification has been around Colombian cyclists who did well in Europe beginning in the early-1970s such as Cochise Rodriguez and then gained dominance in the 1980s with figures like Lucho Herrera, considered (until now) to be the high-point of Colombian accomplishment in international bike racing. Since that time, goes the consensus here, the doping epidemic became so pervasive in professional cycling that Colombians (who are thought not to dope) were put at a disadvantage. But now that doping is under control, Colombians are once again becoming dominant, with their natural abilities borne of (it is believed) a combination of extreme geographic conditions (mountains and altitude) and their hard work ethic (especially those, like Quintana, who come from hard-working farming backgrounds).

In a timely editorial in El Espectador called “The Revenge of the Bicycles” the other day, a prominent news journalist made an interesting observation that mildly challenges this essentializing view. Even while such ideas might have some validity, he says, there is a more simple dynamic at work: Colombian success in bicycling is related to the fact that it is one of the only truly accessible and inclusive sports here because roadways are free, so anyone can do it no matter what social class they might come from. Other sports are expensive and the spaces used for them charge money. The victories of these cyclists from humble backgrounds, he says, is a revenge against this country’s business community and elites who exclude the poor and would just as soon run the bicycle rider over in their large SUVs with tinted windows.

In a timely editorial in El Espectador called “The Revenge of the Bicycles” the other day, a prominent news journalist made an interesting observation that mildly challenges this essentializing view. Even while such ideas might have some validity, he says, there is a more simple dynamic at work: Colombian success in bicycling is related to the fact that it is one of the only truly accessible and inclusive sports here because roadways are free, so anyone can do it no matter what social class they might come from. Other sports are expensive and the spaces used for them charge money. The victories of these cyclists from humble backgrounds, he says, is a revenge against this country’s business community and elites who exclude the poor and would just as soon run the bicycle rider over in their large SUVs with tinted windows.

Though I like the spirit of his point, the story is perhaps not so simple, given the non-inclusive dynamics of bicycle racing in this country. There are implicit and explicit gender issues at work here. The reality is that this racing victory–as is the case with bicycle racing in this country more generally–is implicitly read through masculine eyes and as a masculine victory given the lack of women’s presence in road racing. (This does not mean that there is no recognition of women as protagonistic cyclists, as the case of Mariana Pajón who is a world champion BMX rider and national figure here demonstrates, just that road racing here is considered a men’s sport.) Another reading of the victory was expressed in a newspaper cartoon I saw in which a man on a bicycle is wearing a pink jersey, and his companion says “The marvel of sport…now pink is a men’s color” (Naior, as the winner, wears the “maglia rosa” or pink jersey). The cartoon was drawn by a man, as the sarcasm in it made evident.

In any case, this victory is set against a backdrop in which it is widely believed that good news can be hard to find in this country. As one commentator notes, “In the middle of political chaos, social difficulties, economic problems, the crisis in values, insecurity in cities, the jealousies of some journalists, the brand wars between sponsors, the preferences of each population or region, and of the terrible inequality in the countryside, the only collective pleasure we have in Colombia is that which sports give us.” Historic day indeed.