As a final exploration of Salmon Hole for this blog, I headed to special collections in the Bailey Howe Library. Although this week is not the end of my journey with Salmon Hole, it was an emotional experience.

To be honest my relationship with history is somewhat lackluster. So, treading down towards the basement into the depths of the library, the scent of musty books becoming more aggressive, I did not anticipate an exciting experience. I pictured a grumpy person decades older than me sitting at the desk, annoyed by yet another technology obsessed, disrespectful young adult. Walking up to the desk I held my breath.

The woman looked up and asked, “How may I help you?” I then stumbled through an explanation of our project; mumbling through the words ecology, history, natural resources and Salmon Hole. For a second I thought, “She knows… you don’t know what you’re looking for, you know nothing… She definitely thinks you’re just another annoying kid.”

To my surprise she lead me to a computer. Palms sweaty, I worried she may test me on my knowledge of God knows what… Instead she spent the next ten minutes with me, showing me how to look through the special collections catalogue. She knew exactly what books and reference materials to look for. She was excited to help me. All of the sudden, I was excited to learn from her.

I spent three hours looking through the first two books she told me about, and she gave me a list of about ten. That’s what she called “getting an overview”.

Walking into the library I did not expect to come out utterly amazed and excited by the wealth of knowledge hidden in the depths of the lower floor.

One of the first materials I looked at was titled, “The identification and characterizations of Burlington Vermont’s wetlands and significant natural areas, with recommendations for management”. Essentially this document was a study done by Jeff Parsons a Vermont ecologist in 1988. The document, over one hundred pages in length, read much like something we might read for NR1 today. I was shocked by the principles and values portrayed in the work, values I am just beginning to understand in the context of my own life. The first few pages are dedicated to an introduction of sorts, explaining what wetlands and natural areas are, and why they are important. According to Parsons, on page seven, zoning laws are concerned with promoting “public health, safety, morals, and general welfare,” in addition they may also “promote values which are spiritual as well as physical, aesthetic, and monetary.” Although the document is still very much from the view point of Western Ecological Knowledge, Parsons ensures the reader that legally the purpose of these areas is also for a connection to the nonhuman world (Parsons, 7).

Additionally I learned that in the 80s Vermont had actual legislation defining a wetland, that Parsons quoted for reasoning behind the areas he examined. The rest of the document is dedicated to wetland and natural area descriptions and suggestions for how to better them, however these suggestions are mostly ways to protect the areas. On page seventy-one, Parsons suggests the protection of the wooded ravines near Riverside Avenue, which is the wooded area that guides the path to Salmon Hole. I don’t know if any significant actions were taken after the publication of Parson’s work, however it was very interesting to see what people were thinking about ten years before I was born.

Parsons also makes a significant point that the words used to define places and ecology are extremely important in the preservation process. Suddenly the words of Robin Kimmerer, author of “Braiding Sweetgrass”, entered my mind. Robin believes that living things should not be referred to as “it”, because it takes the life out of them and is simply disrespectful. Although Parsons and Kimmerer, share slightly different viewpoints, they both share the significance of words in relation to ecology.

Looking back on my past visits to Salmon Hole, I realized that I have simply been trying to identify things. And for now that’s okay. However, the more the material and lessons from this course sink in, the more I realize that identification is only a minuscule part of the process. I think maybe that’s why I connected on a deeper level with the Heald Street Orchards as opposed to Salmon Hole. At home I had that personal story connection to the living things there. At Salmon Hole I have yet to really experience or appreciate anything but the names.

Now reading over my research in special collections, it’s nothing but names.

After having this realization I decided to return to the library and try to piece together more of a story for all of the living things that consider Salmon Hole home.

One book I had not gotten to on my first visit, “The Mills at Winooski Falls” seemed like a good place to start. The book is a collection of perspectives on the story of the Mills that shaped the town of Winooski and Salmon Hole as a natural area.

The biggest change to Salmon Hole began in 1830, with the construction of the first dam. Before this time Salmon Hole was known for the plethora of Salmon and the now endangered Lake Sturgeon. To this day the dams, that have failed, been rebuilt, failed again, then rebuilt again, play a major role in the health of the ecosystem of Salmon Hole. The dams lay in the path of the salmon’s spawning route, due to the block they are not able to travel upstream to reproduce. It wasn’t until the mid 1970s that people began efforts to help the spawning of the salmon.

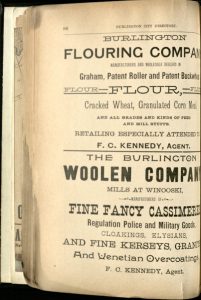

In addition to the dams, the mills of Winooski, in particular the Burlington Woolen Company, caused great problems in the river. During the 1880s, Winooski’s sewage system and the dyes from the Mills drained directly into the River. Then in the 1920s sulfuric acid from a carbonizing plant was dumped directly into the ecosystem.

Fact after fact, human life has had an adverse effect on Salmon Hole, the home of so many beings.

Some other interesting bits of information I gathered during my time in special collections:

- The Abenaki inhabited the land since the Archaic Period, calling Salmon Hole, Namas (Fish) kik (place).

- By 1890 the Abenaki had no land around Salmon Hole. My phenology spot lies on a section of land that was owned by Edward Dumas the watchman of the Burlington Woolen Company, who owned the other section of land.

- Based on my gatherings, the land around the river was predominantly cleared at the time. And this is evident in the young growth in the area.

- The mill closings had a significant impact on the Winooski community. Many of the families were working immigrants from France, Ireland, Poland, Italy, and England depended on the Mills.

- In “The Mills at Winooski Falls”, stories of families separated in order to find work were common. A popular destination for people looking for work was Lowell Massachusetts, as the Mill business was stable and thriving in comparison to Vermont.

- The American Woolen Company did not close until 1955.

- The flood of 1927 destroyed the dams by Winooski Falls, and was due to much of the deforestation occurring in the area.

- After the floods the land was dynamited to make way for water to drain.

- According to Parson’s report, the geology of Salmon hole is entirely Ordivician Dolomitic Limestone from the Shelburne Formation.

- It appears to be a light grey or white color.

- The rock breaks down in chunks and slabs, it doesn’t crumble and is not sculpted by the river.

- In 1980 when the book “Waterfalls, Cascades and Gorges of Vermont” was published, the river was reportedly, “mildly polluted” with a “river smell”, “murky color”, and some “junk and foam floating in the eddies.”

- Also the book presumes that before the dam construction of 1830, the area was most likely a natural waterfall.

- The book also includes a list of some of the most common Vascular Plants

- Populus Tremuloides – Quaking Aspen *

- Toxicodendron Radicans – Poison Ivy *

- Anemone Multifida

- Salix spp – Willow

- Fragaria Virginiana – Wild Strawberry *

- Campanula Rotundifolia – Bluebell Flower

- Andropogon Gerardi – Big Bluestem *

* – Still there (to my knowledge)

The list continued, however I did not have time to look into all of the species.

As I wrap up my final blog, I can’t help but continue to reflect on the words of Robin Kimmerer. Still, even understanding the importance of respecting the beings I refer to, I found it hard to avoid using the word “it” when talking about living things or the geology.

However, I know that my experience this semester exploring the pieces, patterns, processes and beauty of Salmon Hole that my appreciation and understanding has grown greatly. I have gone from someone who defined the experience with the birder in the Orchards as quaint, to someone who has a maturing appreciation and love for the systems that support my life.

I will end with a quote from Henry David Thoreau,

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

Before Salmon Hole and NR1 I could not appreciate this quote I have heard so many times. I am grateful for this experience, because being outside, learning from life around me, when I come to die, I will have lived.

- Burlington Woolen Company Advertisement (Burlington City Directory, 1890)

- Photo of Salmon Hole near my Phenology Spot (Jenkins, 1988)

Jenkins, J. (1988). Waterfalls, Cascades and Gorges of Vermont (pp. 199-202) (Agency of Natural Resources). Waterbury, VT.

Krawitt, L. (Ed.). (2000). The Mills at Winooski Falls. Burlington, VT: Onion River Press.

Parsons, J. (1988). The Identification and Characterization of Burlington, Vermont’s Wetlands and Significant Natural Areas, With Recommendations for Management (Vol. 5, pp. 4-71, Rep.). Burlington, VT.