While visiting my site this week, I sadly did not notice much change since the previous visit. The same buds were beginning to bloom, the same dandelions started to sprout, and the wild strawberry was beginning to poke up out of the ground. This week had rain showers on multiple days, but the water levels were lower than normal. The water striders were skipping around the stream.

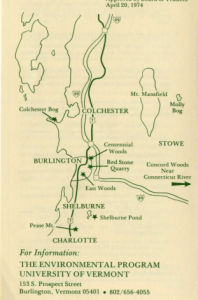

Since my phenology spot is at Centennial woods, it is the perfect representation of the connection between nature and culture. Burlington, and Vermont in general, have a culture where outdoor recreation is common. This love for the outdoors exists in some places, but not so prevalent as at the University. Centennial Woods is used as a place where locals and students can hike, walk, hammock, snowshoe, etc. It is used constantly by the people of Burlington as a haven from the city. This makes Centennial Woods an integral part of Burlington.

The woods have certainly been an integral part of my life in Burlington. After continually going back to them week after week, month after month, I feel a connection to this plot of land. Watching the plants change through the seasons has made me feel like I am a part of this this, as I too have changed from season to season. Just like the phenological cycle, college brings about change over time. Being able to see physical change, has helped me through my emotional change. For this reason, I will forever be connected to my phenology spot.

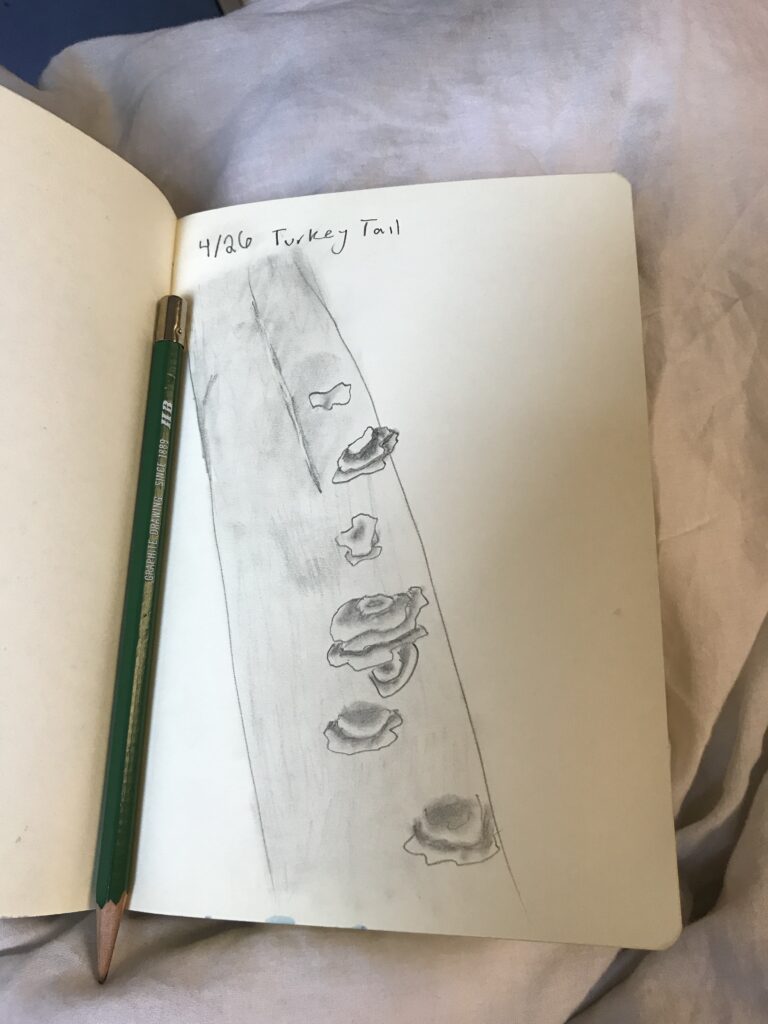

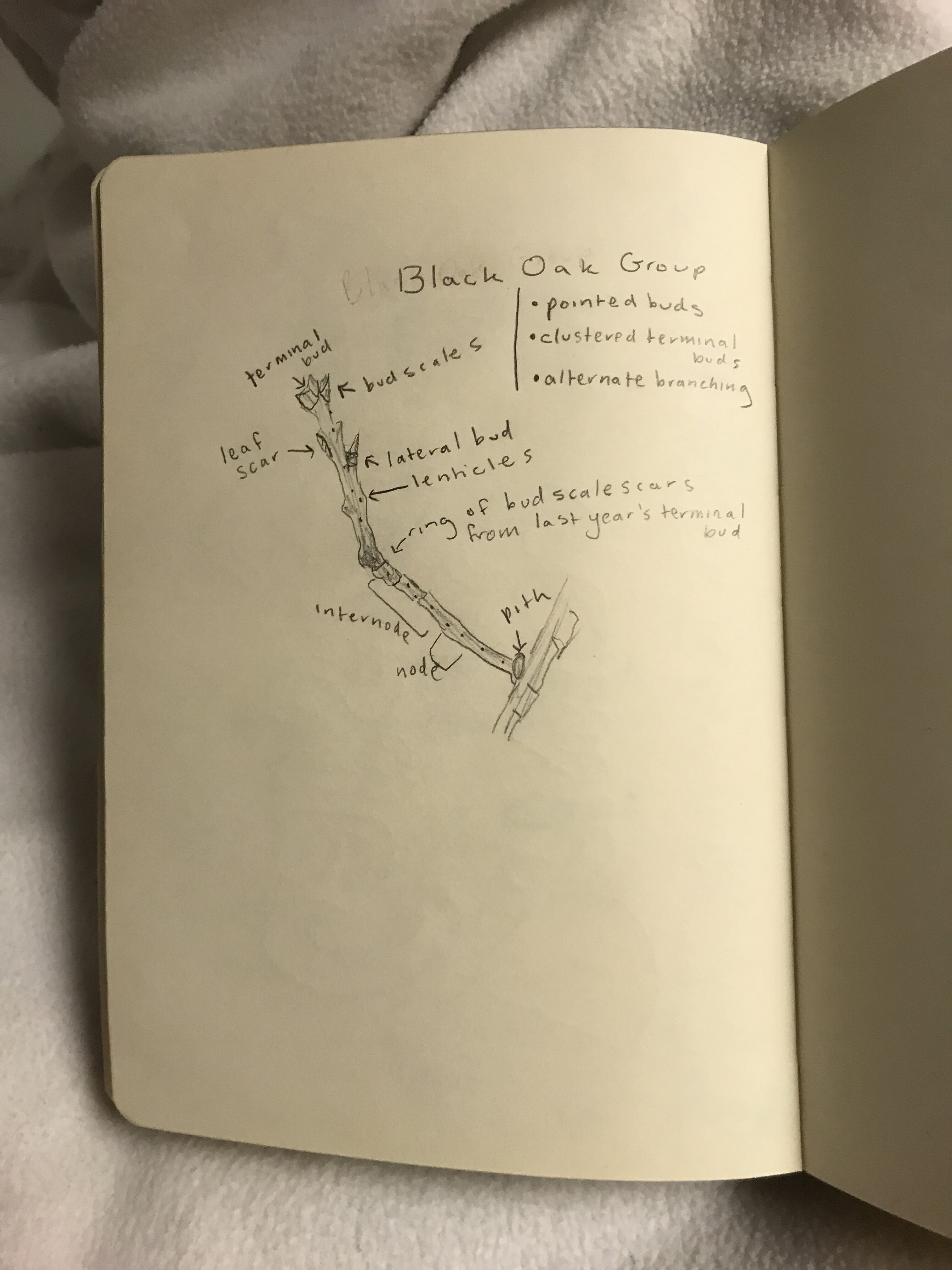

Here are some photos I took while at my spot:

Photo taken by Emily Johnston.

Photo taken by Emily Johnston.

Photo taken by Emily Johnston.

It’s melancholy to leave this area and the beauty that surrounds it. Next fall, when I return for classes, I will be so excited to see changes at this spot. After learning so much this semester, I am ready to apply it to land back home, but I will miss Centennial Woods.