I woke up to the sun streaming through my dorm room window. Stepping outside, I felt the cool spring air hit me and the blissfully fresh smell of the annual melt. My friends waved at me and shouted brief greetings as I passed them. It was, by all accounts, a normal day and I felt like a normal person enjoying the beautiful spring weather. The only thing out of the ordinary was the woman leaning out of her window, slowing her pace to be able to yell at me while I made my way to class.

Some people walk to class, some people further afield drive, and some of us ride our bikes. I had encountered a fellow person-who-rides-a-bike in the bike lane who was traveling much slower than I was, so just like I would when driving my car, I decided to pass them when it was safe. I checked over my shoulder and saw only a red car much further down the road, so I passed on the left, re-entered the bike lane, and kept pedaling.

The red car I had seen suddenly sped up, and a middle-aged woman was leaning out the window.

“HEY, F*** YOU! You do not get to use the road. I don’t know what you’re thinking, pulling moves like that. Stay in your lane, you f***ing cyclist!” There was more, but the silent rage that flooded me blocked out whatever it was. I sat through the rest of my classes fuming.

The bubble of people hating ‘cyclists,’ or at least their involvement on the road, has been a constant through my years riding bikes. I’ve also seen and heard of my fair share of friends and family getting in bad scenarios, my friend had a bag of popcorn dumped on them, my dad had someone in a truck pull over and step out of the cab swinging a chain overhead, and even more friends have been hit, with injuries ranging from some cuts to broken ankles to death. I wondered what inspired such animosity on the road until I spoke with my dad about it.

My father has been in the bike world since he was 17, and he’s got many more accounts of things being yelled at him, of being treated like he wasn’t human while riding. The advice which I’ve taken to heart was this: “I try my hardest to never, ever respond to anything. I don’t wave, I don’t smile, I don’t flip the bird, I don’t do anything. Because those people who run you off the road, who yell at and dump things on you – they already don’t see or respect you as a person, and who knows what they’ll do to you if provoked?”

They already don’t see or respect you as a person. Why? That line struck me as incredibly odd. I think of myself first and foremost as a person. Where’s the difference between a person in a car, a person walking, or a person on a bike?

Perhaps it’s the spandex (or maybe the shaven legs?) that make cyclists seem like a different group of people.

I think it comes down to nomenclature. Look in any of multiple online forums or Facebook arguments, and it becomes clear that there’s a distasteful association with the word “cyclist.” Perhaps it stems from the alien nature of elite road racers from years past. Lacking a typical “American dream” 9-5 job, shaving their legs, and wearing form fitting spandex, these racers can seem far removed from casual society.

Thus, the word cyclist became associated with an elitist tone, of people who were not normal. And once a negative tone is set in place, it’s hard to shake.

The way that we use words to describe everything in our lives heavily influences how we perceive and judge those things. Words have power. It’s a tired saying, perhaps, but one that bears repeating. Words have power. In a study from Loftus and Palmer, a handful of randomly selected students watched a taped recording of two cars involved in a low-speed collision. Given the low speed of the crash, there were no broken windows, and no one got hurt.

After being shown the tape, the students were placed into 5 separate groups and asked how fast the cars appeared to be going at the time of the incident. The average speeds ranged from 31.8 miles per hour to 40.8 miles per hour. The only difference was in the phrasing of the question asked to the student.

One group of students were asked “about how fast were the cars going when they contacted each other?” The next was asked the same question, but the verb was changed to hit. Then to bumped, then collided, and the final group were asked “about how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?”

Students from the group that heard the question with the word ‘contacted’ guessed the slowest speed, at 31 miles per hour. The more violent the verbal label got, the higher the speed estimate got.

| Verbiage used | Average speed estimate (mph): |

| Smashed | 40.8 |

| Collided | 39.3 |

| Bumped | 38.1 |

| Hit | 34.0 |

| Contacted | 31.8 |

Not only was there a direct correlation between the rising aggression of the label and the student’s perceptions, but the more egregious language caused the students to misremember parts of the video. Students from the “smashed” question group also replied seeing broken glass, of which there was none.

Loftus and Palmer did a second trial, with different students, to test whether that was a universal reaction. 150 subjects watched the same video. This time, 50 people were asked the average speed when the cars smashed together, 50 when the cars hit each other, and 50 weren’t questioned about the speed at all. A week later, the same three groups took a test which held a randomly placed question: “Was there any broken glass?”

Despite there not being any broken glass anywhere in the video, the test subjects who heard the question asked “smashed” reported broken glass more than twice that of the group asked “hit” or not at all.

| Response | Smashed | Hit | Control |

| Yes | 16 | 7 | 6 |

| No | 34 | 43 | 44 |

Clearly, there’s an association between our language and our perception of the world around us. In the case of cycling, such distinctions can hold extreme ramification for our well being. By verbally labeling all people on bikes as “cyclists,” all the negative connotations of the word come with it, thus changing others’ perceptions about those people riding. That’s where a lot of problems stem from: assumptions of skill or about their belonging on the road at all, which should not be up for debate.

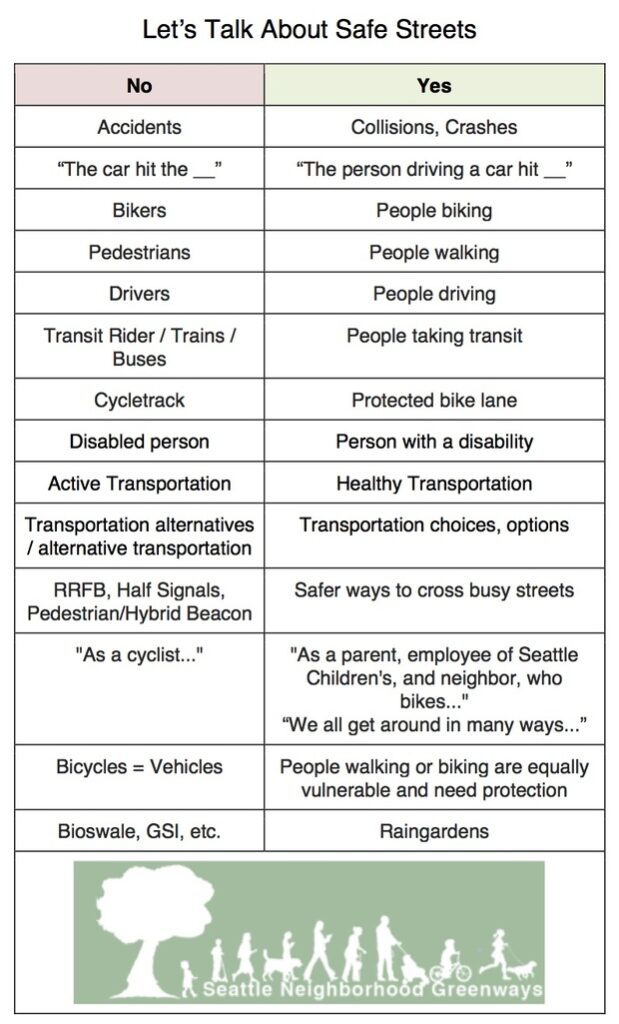

By changing our verbiage to “people on bikes” or “person who rides a bike,” we’re admitting a crucial factor: we’re all people. This should extend to all factors of the road, too. Cars and other motorists should be referred to as people driving, pedestrians as people walking. This forces a shift in perspective to consider all of each other’s humanity, which is an essential part of having a cooperative public system, in this case transportation.

One facet of safe transportation could be protected bike lanes, giving people on bikes their own designated space akin to sidewalks. Unfortunately, discussions of such frequently devolve into unproductive civic debate over who deserves what. What starts out as an idea of improving safety for all can become an emotionally driven “war on cars.”

A group advocating road safety in Seattle focused on being “neighborhood advocates.” While they did largely push for safer bike infrastructure, they focused on changing the way they talked about everything – putting people in front of their transportation methods, and referring to things like pedestrian beacons as “safer ways to cross busy streets.”

The result they found was everything being accepted more readily by the public. By focusing on our shared humanities as members of the community and keeping all parties safer as opposed to just people on bikes, discussions and debates became more civil and Seattle was able to increase the pace and number of bike lanes they put in.

Another usage from the article focused on was “crashes” or “collisions”, as opposed to “accidents.” Their example was the headline “Deadly Crashes Between Cars and Cyclists Happening at an Alarming Rate.” Here’s a pulled piece: “While the headline uses “crashes” instead of “accidents,” the wording doesn’t acknowledge that people are driving the cars, while it puts the people riding bicycles into a category that is easy to see as “other.” The verb “happening” makes the increase sound more like an unavoidable natural phenomenon rather than the result of inadequate infrastructure or human error. ” – Sarah Goodyear

The thing is, it is avoidable.

Try it at home: reading out loud, compare the headline above with “person driving a car crashed into person on a bike.” The first has a feeling of apathy, which is incredibly dangerous. Apathy easily creates dangerous situations for others, especially when sheltered by climate controlled ~4000 pound hunks of steel. The second statement, meanwhile, places equal emphasis on both parties involved, specifically their shared trait – their humanity.

As long as we all remember that, and make decisions and actions focused towards respecting everyone and their safety, things should turn out alright, like in Seattle. Just like the over-zealous gentleman who mistakenly accused Obama of not preventing 9/11, care must be given to our word choice to avoid inaccurate and gross comparison. We’re not individual members of “team car / cyclist / pedestrian,” we’re all just people. People trying to do our own thing, where a bit of mindfulness goes a long way.

Tom Fucoloro in Seattle put it best: “It’s understandable why people default to ‘accidents’ and other usages. It’s to avoid thinking about the fact that driving and commuting is the most dangerous thing we do on a regular basis. But we need that sense of personal responsibility to make streets work.”