According to a U.S. Department of Agriculture-funded study, lack of access to affordable health insurance is one of the most significant concerns facing American farmers, an overlooked risk factor that affects their ability to run a successful enterprise.

“The rising cost of healthcare and the availability of affordable health insurance have joined more traditional risk factors like access to capital, credit and land as a major source of worry for farmers,” said principal investigator Shoshanah Inwood, a rural sociologist at the Ohio State University, who conducted the study with colleagues at the Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis at NORC at the University of Chicago.

“The study found that health-related costs are a cross-sector risk for agriculture, tied to farm risk management, productivity, health, retirement, the need for off-farm income and land access for young and beginning farmers,” said Alana Knudson, co-director of the NORC Walsh Center.

Preventative care is a priority for women

The study found that access to preventative health care was a particular concern for female farmers and ranchers. “We heard how important coverage for things like routine screenings, pre-natal care and well-child visits are to women operators,” says Inwood. “It’s important to them that their children have that kind of coverage, too.”

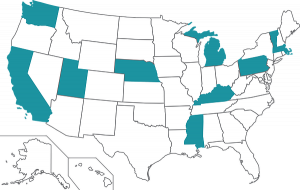

Study results were based on a March 2017 mail survey of farmers and ranchers in 10 study states and interviews with farm families in each of the study states in 2016.

Researchers surveyed 1,062 farmers and ranchers from these 10 states, providing regional diversity and a mix of states that have expanded or not expanded Medicaid.

Three of four farmers and ranchers (73 percent) in the survey said that having affordable health insurance was an important or very important means of reducing their business risk. And just over half (52 percent) are not confident they could pay the costs of a major illness such as a heart attack, cancer or loss of limb without going into debt.

Insights from the interviews supported the survey results. “During the course of interviews with farmers, many relayed stories about their family members or neighbors who had lost their farms or dairies due to catastrophic illness or injury when they were uninsured,” Knudson said.

Sixty-four percent report having pre-existing conditions

To meet the needs of farmers, changes in current health insurance law will need to be carefully considered, the survey suggests.

Two out of three farmers and ranchers (64 percent) reported having a pre-existing health condition. With an average age of 58, farmers and ranchers are also vulnerable to higher insurance premiums due to age-rating bands. And among farmers and ranchers 18 to 64 years old, one out of four (24 percent) purchased a plan in their state’s insurance marketplace.

“A number of farmers in their 50s we spoke with said they had left off-farm employment in the last five years to commit to full-time farming because they and their families would not be denied health insurance in the individual market due to pre-existing conditions,” Knudson said.

Health Insurance costs create barriers for young and beginning farmers

Health care costs also factor into farm succession issues, potentially denying young people access to land to farm.

Almost half (45 percent) of the farmers surveyed said they’re concerned they will have to sell some or all of their farm or ranch assets to address health related costs such as long-term care, nursing home or in-home health assistance.

“These findings indicated that many farmers will need to sell their land, their most valuable asset, to the highest bidder when they need cash to cover health-related costs,” Inwood said, “making it more difficult for young farmers to afford land and increasing the likelihood farmland is sold for commercial development.”

Lack of access to affordable health insurance could potentially drive young people away from farming, the research found. Young farmers who had taken advantage of the Medicaid expansion in their states said told the researchers in interviews that it allowed them to provide health insurance for their children and have time and energy to invest in the farm or ranch rather than having to seek a full-time off-farm or ranch job with benefits.

Most farm families have health insurance, over half through public sector employment

The vast majority of farmers and ranchers (92 percent) reported that they and their families had health insurance in 2016 but that it frequently came from off-farm employment.

Over half (59 percent) of farm and ranch families received benefits through public sector employers (health, education and government).

“Public sector jobs, especially in rural areas often offer the highest wages and most generous benefits,” Inwood said. “Changes in public and private sector employment options or benefits affect the financial stability and social well-being of farm families with impacts reverberating through rural communities.”

Nearly three quarters say USDA should represent farmer interests

Given the pressing nature of their health insurance concerns, farmers are also seeking help from the federal government. Nearly three quarters (73 percent) of farmers said USDA should represent farmers’ needs in national health policy discussions, particularly due to unique health needs of farmers and farm workers (e.g., coverage for blood tests to examine potential pesticide exposures).

The timing is right, Inwood said, the five-year update of the U.S. Farm Bill is due in 2018. The comprehensive Farm Bill deals with agriculture and all other issues under the jurisdiction of the USDA.

“We have a shrinking and aging farm population,” Inwood said. “The next Farm Bill is an opportunity to start thinking about how health insurance affects the trajectory of farms in the United States.”

For the study, a total of 1,062 farmers and ranchers were surveyed in March 2017 in Vermont, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Nebraska, Mississippi, Kentucky, Washington, Utah and California. Study states were selected in each of the four Census regions and included a mix of those that had expanded or not expanded Medicaid. The study results were also based on interviews of up to 10 families in each of the study states.

The study was funded with a $500,000 grant from the USDA’s Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (AFRI) as part of a National Institute of Food and Agriculture initiative designed to increase prosperity in rural America.