By Arden Jones

If you can afford to buy all of your food at a farmers market, it doesn’t necessarily mean you care about fairness and equality. This is the message Alison Alkon brought to a packed Livak Ballroom on the UVM campus in September. Alkon described how the added values of local food can be seen as premiums we pay for environmental, health, and social justice goals. But many white Americans may be more concerned with environmental motives above others when it comes to buying food.

Alkon’s research has revealed discrepancies between blacks and whites in terms of food access and priorities in supporting local agriculture. Her study of two farmers’ markets in the San Francisco Bay area focused predominantly on the racial discrepancies of food access and market channels. Alkon’s topic of research provoked us to think more critically about our own local foods systems. Is Vermont’s movement toward sustainable agriculture founded in social justice motives as well as environmental and economic ones?

Alkon’s research has revealed discrepancies between blacks and whites in terms of food access and priorities in supporting local agriculture. Her study of two farmers’ markets in the San Francisco Bay area focused predominantly on the racial discrepancies of food access and market channels. Alkon’s topic of research provoked us to think more critically about our own local foods systems. Is Vermont’s movement toward sustainable agriculture founded in social justice motives as well as environmental and economic ones?

Linda Berlin, of UVM’s Center for Sustainable Agriculture has worked on food justice related issues in Vermont for many years, having chaired the organizations like the Vermont Community Garden Network (VCGN) and Hunger-Free Vermont. Since working with Farm-to-Plate she has seen that there are different types of social justice issues here. For one, although Vermont certainly faces some issues related to race, a relatively low level of diversity makes it easier for us not to address them.

Through focus groups, Berlin and her students have begun to explore some deep-seated subconscious beliefs that Vermonters hold about who deserves access to good food. She has found that, “sometimes people think that those [race issues] aren’t issues that we face as much,” and maybe this is because many Vermonters who have lived here their whole lives have not had the experience that enables them to respond to other races. In essence, it is a non-issue. But, Berlin says, it should be. “Everything we do is about relationships,” she claims, and, just as we reevaluate our places on earth, so should we reach out to confront our relationships with people different races and backgrounds from our own.

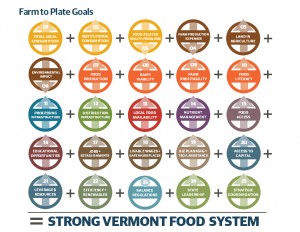

A local example of one organization that has done this is the Center for Whole Communities near Waitsfield, VT. CWC has followed this mantra of finding an intersection between human and environmental rights for over a decade. Their work started in Vermont and has spread across the nation through alumni of their Whole Thinking Program. One could argue that Vermont as a whole strives to support these same ideals in the Farm-to-Plate movement, which includes many interrelated goals of social justice.

The #1 goal of the Farm to Plate strategic plan is to increase total local consumption of food. It is estimated that between 2.5 and 5% of food dollars spent in Vermont is spent on locally produced food, and we want those numbers to go up. The goal is simple, but the methods of achieving it inherently involve a change in market access and prices, which have deeper roots. Goal #13 is increasing local food availability (“Local food will be available at all Vermont market outlets and increasingly available at regional, national, and international market outlets”), and Goal #15 is to increase food access (“all Vermonters will have access to fresh, nutritionally balanced food that they can afford“). Increasing livable wages and safe workplaces (Goal #18) are also tied to social equality.

Many of Alkon’s themes and approaches to research could be applied to gender studies, and Alkon even alluded to her interest in pursuing further the theme of women in agriculture and institutional prejudices that surround them. Alkon said, “One thing that I think is really under-theorized in cultivating food justice, and that I am really excited to see go a little further is work on food justice and gender… It has kind of gotten a little pushed to the side.”

But has it? Food justice and gender is one way of describing the disparity between livelihoods of men and women in sustainable agriculture. From my perceptions as a newcomer to Vermont, sustainable agriculture and the livelihood that surrounds it seem to go hand in hand. So called “quality of life” is a major aspect for many small farmers in decisions about their business plans. For many, especially women farmers, this can include being close to their family, having time to spend raising children, and forming the community ties that are inherent with local food production.

The Women’s Agriculture Network (WAgN) has helped not only in alleviating some of the institutional prejudices against women farmers, but also in making issues such as child and healthcare less problematic for full-time farmers who don’t enjoy the benefits that may come with an off-farm job. It seems as though Alkon is more concerned, however, in food systems that actively work to change the status of all underserved individuals, despite whether they are farmers or just consumers.

The lecture pushed the audience to more deeply consider the ethical roots of their local food systems, and to discern the actual ecological and socially responsible initiatives from what may be marketing ploys for a privileged audience. Part of the problem is that there is not yet any means by which we rank social goodness of our products the way we have begun to environmentally with GMO labeling and the like. Alkon called the concept of a Green Economy, “undemocratic,” making the point, “If we are voting with our dollars, than those of us with less dollars get less votes.” Instead of looking to a commercial food market to set prices, the value of the goods should derive from how much the product supports social equality, mobility, and access to good food. It is always good to remember that, as good as Vermont is at this local food stuff, there is always room to do better.

The lecture was sponsored by the Food Systems Graduate Program at UVM, the Food Systems Initiative, Department of Geography, and the Department of Sociology.

About Arden Jones

Arden is an intern with the Student Conservation Association (SCA) and is working on the UVM Extension New Farmer Project this fall. She is a recent graduate of Sewanee: The University of the South where she majored in Natural Resources. Now Arden is getting her feet wet in sustainable ag!

Arden is an intern with the Student Conservation Association (SCA) and is working on the UVM Extension New Farmer Project this fall. She is a recent graduate of Sewanee: The University of the South where she majored in Natural Resources. Now Arden is getting her feet wet in sustainable ag!