What does climate change look like in a Northeast forest ecosystem? Many of us know that climate change and global warming are pressing matters, but it can be difficult to conceptualize of what that means for the forests around us. In general, ecosystem change as a result of climate change is slow and may not be obvious. Global warming is an issue that we face every day as it threatens the health of our forest ecosystems. As a result of global warming, more specifically the rising annual temperatures and increase in precipitation, many species of trees are experiencing range shits, which means the area in which they can live is shifting Northward, and so are the trees.

Although much research has been done on the predicted locations and drivers of range shifts for tree species, comparison of these shifts and the lasting impacts they will have is lacking. When a species moves from one location to another, there are often ecological and societal/economic impacts that come with it. Three species that show clear signs of this issue are the Northern Red Oak, Sugar Maple, and Balsam fir.

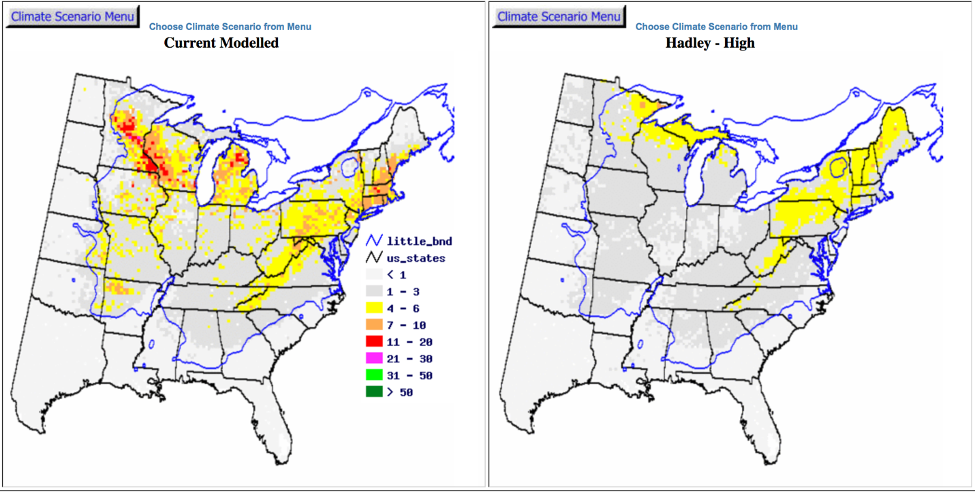

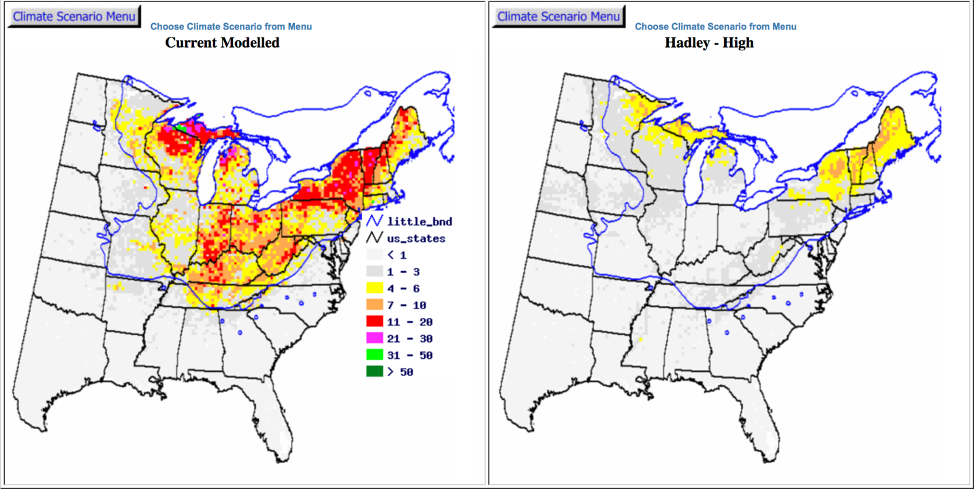

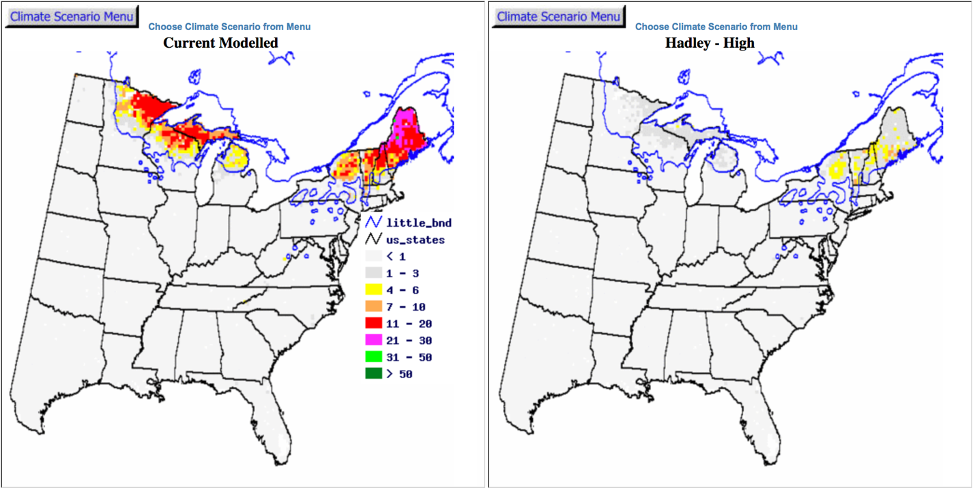

The Climate Change Tree Atlas from the US Department of Agriculture’s Northern Research Station shows that between Northern Red Oaks, Sugar Maples, and Balsam Firs, predicted range shifts vary in extremity.

Every Species is in Danger

The movement of the distribution of Northern Red Oaks will be the least extreme of the three species and so will have the least amount of impact on other living things in the forest. This is good news for deciduous hardwood ecosystems where Northern Red Oaks are a keystone species (a species that the whole ecosystem revolves around and relies on). On the other hand, Oaks are also a source of economic value in the timber industry as their woods is commonly sought after for high end furniture or interior building. Timber companies are often prevented from clear cutting in order to comply with environmental regulation. If the abundance of Northern Red Oak decreases, production amount of timber per unit of land will also decrease.

The movement of the distribution of Sugar Maples has much larger implications for the economy given that sap for the maple industry is harvested in a very sedentary manor. If the locations of sugarbushes (sap harvesting sights) are no longer viable options for the trees to thrive in, millions could be lost in the movement of harvesting locations. It is of much concern to the industry that the sugaring season is already beginning to shorten and moves earlier and earlier each year as the spring thaw happens faster and earlier than before. This, plus their predicted range shift, may cause devastating loss for the maple industry.

Unlike hardwood species (like Maple and Oak) the range shift of Balsam Firs is two-dimensional. The conditions required for Balsam Firs to thrive are currently found in the alpine and sub-alpine zones in mountainous regions. As the climate becomes more temperate (warmer and wetter) not only will their viable habit shift Northward in search of colder conditions, but also up in elevation. This will be most noticeable on mountain slopes where the appearance of Balsam Firs is a clear marker of the beginning of the sub-alpine zone and the disappearance of which delineates between alpine krummholz and alpine tundra biomes. With alpine elevation gradients in temperature and precipitation being the most susceptible to climate change, the Balsam Fir’s range will be one most effected by climate change, their range shift will not have the most negative effect.

The Order of Impact

From this information, it’s easy to make generalizations about types of forests and their range shifts. Range shifts will occur from most extreme to least extreme in mountain spruce-fir forests/alpine krummholz (Balsam Fir), Northern hardwood forests (Sugar Maple), then cove hardwood forests (Northern Red Oak). This order only applies only to the extremity of the range shift and not the impact the shift will have. In order form most extreme to least extreme, the species range shifts that will cause the greatest lasting ecological impacts are the Northern Red Oak, Balsam Fir, then Sugar Maple. In addition, in order from mostextreme to leastextreme, the species range shifts that will cause the greatest socio-economic impacts are the Sugar Maple, Northern Red Oak, then Balsam Fir.