To affect the working landscape, we know we have to start small – “small” as in the tiny particles and droplets and microbes that make up healthy soil. We start with the microcosm of the soil for a simple reason: if we want a vibrant Vermont with clean water, great food and a robust farm economy, we need to make sure farmers can build the health of their soils.

That seemingly simple premise is at the foundation of much of the work of the Center for Sustainable Agriculture. And it’s the guiding force behind the research that’s being hosted by Philo Ridge Farm, where Pasture Program Technical Coordinator Juan Alvez, Ph.D., is engaged in several long-term applied projects to investigate the practices with the highest promise for productivity and profitability, as well as building and maintaining ecological balance with the land.

Doing this means looking in depth at many of the elements of the farm’s systems, investigating how soil, crops, animals and forest can all thrive. We seek to understand more about how a healthy farm ecosystem can support a profitable business, and under what conditions.

Among the questions we’re asking are:

- Can we combine agroforestry practices in ways that contribute to animal health and growth as well as providing benefits to soil, water and wildlife?

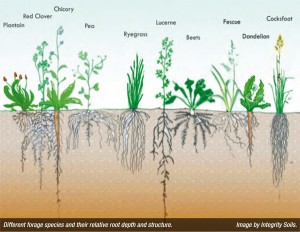

- What forage species can grow well in a partly forested (shaded) area, and serve the multiple purposes of promoting animal weight gain while helping break up compacted soils? (Curious about these? We’ll share some of Juan’s early observations: “Based on last year, the most productive species was sorghum sudangrass. And we saw that reed canarygrass will outcompete everything else, so we’re pulling that out to see what kind of species diversity we can encourage.”)

- How can the practice of bedded pack barns contribute to animal comfort as well as building soil fertility?

- Can we combine precision irrigation with “cocktail cover crops” to keep land, plants and animals as healthy and productive as possible, ameliorating the “summer slump” and grazing longer into the winter as well?

We look forward to sharing information with farmers, colleagues and other researchers at upcoming pasture walks and in upcoming newsletters and articles.

In the meantime, want to know more?

- Read more about the research project on the Center’s Research pages.

- Plan to attend the August 15 Field Day at the farm to learn about the research, have a pasture walk with noted grazing consultant Jim Gerrish, and meet members of the Vermont Healthy Soils Coalition. Register here.

- Contact Principal Investigator Juan Alvez with questions.

- And if you’re interested in joining a group of passionate volunteers (representing farmers, gardeners, seed savers, researchers and professionals, including several staff members from the Center for Sustainable Agriculture) in the Vermont Healthy Soils Coalition – an online discussion group that one member describes as “volunteers with an interest in shifting the paradigm of how people interface with the land. We operate under the premise that we can restore land water cycles by covering Vermont’s bare soil; nurturing photosynthesis and the biology underground,” please feel free to join the group and let members know how you’d like to participate by taking this short survey.

Originally published in the Center’s Fresh from the Field newsletter, June 2017

Recent Comments