By Juan P. Alvez, Ph.D., Pasture Technical Coordinator. Originally posted December 11, 2015 on the Vermont Pasture Network Blog

In 2013, our research team* embarked on a collaborative, long-term study focused on understanding how ecologic habitat disruption is associated with livestock wellbeing and health, and how that can affect society.

This is far from a local or unique issue. With human population growing above 7 billion people, a demand for higher living standards, including dairy products as more people seek access to all forms of animal protein as part of a more affluent lifestyle, is ever increasing.

Meeting this demand requires both advancing the agricultural frontier and an intensification of the production process, burdening already-degraded ecosystems, and impacting habitats, forests, biodiversity, soils, water and rural livelihoods. There is strong evidence that agriculture receives (and may provide), a diverse array of benefits from healthy ecosystems, and it also worsens problems when it disrupts them.

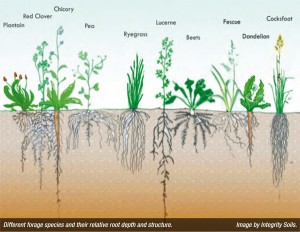

We suggest that managing for increased biological diversity in pasture-based dairy production systems positively contributes to improved livestock well-being, health and productivity, and creates a positive feedback ecological service loop. It has been demonstrated that minimally disturbed soils, adequate access to a diverse, high quality forage mix, and clean water are associated with bovine wellbeing and milk quality. Dairy cows support numerous microbial communities, including mutually beneficial relationships with their microbial

symbionts (rumen microbiota). These cellulolytic bacteria break down plant materials, providing cows with a source of energy and nutrients. An understanding of the response of ruminant and environmental microbial communities to specific management practices will provide an opportunity to both optimize farm productivity and enhance ecosystem-based management.

We had an integral approach to soils, forage and diet, rumen microbiology, grazing activity and milk quality, to evaluate how cows were affected. We hypothesize that biodiversity affects livestock well-being, health, and productivity, and that it may also affect cows’ grazing behaviors. To explore this, we studied how the relationship between grazing time and diet alters rumination activity, rumen pH and health, milk composition and productivity.

Cows that grazed on diverse pastures presented higher concentrations of poly unsaturated fatty acids than when grazing a monoculture; they were able to transfer conjugated linoleic acid and omega-3 fatty acids from these pastures into the milk. We did not find any effects between pasture diet type and lying time but, there were differences among cows in laying time where higher producing cows had longer lying times.

Overall we determined that pasture-based livestock who graze on pastures managed for increased biodiversity can help to improve soil health, optimize forage utilization, rumen activity, milk composition and quality reduce costs, and increase net farm income.

By optimizing these production parameters, pasture-based dairy farmers can simultaneously advance cattle health and well-being, reduce operational costs and environmental impacts and produce the healthy dairy products society is demanding. We hope that our work can explain the importance of maintaining a healthy ecosystem for Vermont farms. Full results will be published on a scientific article.

*Research Team (alphabetical order): Juan Alvez, John Barlow, Melissa Bainbridge, Emily Golf, Jana Kraft, Robert Mugabe and Joe Roman

Sponsors: UVM Reach Grant & NE-SARE Grant

Recent Comments