My Phenology Spot back in DC was in Glover Archibald Park. This map shows the location:

https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1Lt0Z4jZEKTJ5Dm2IhAOFP7DzMBF5KqmC&ll=38.93067903174467%2C-77.08112364612373&z=19

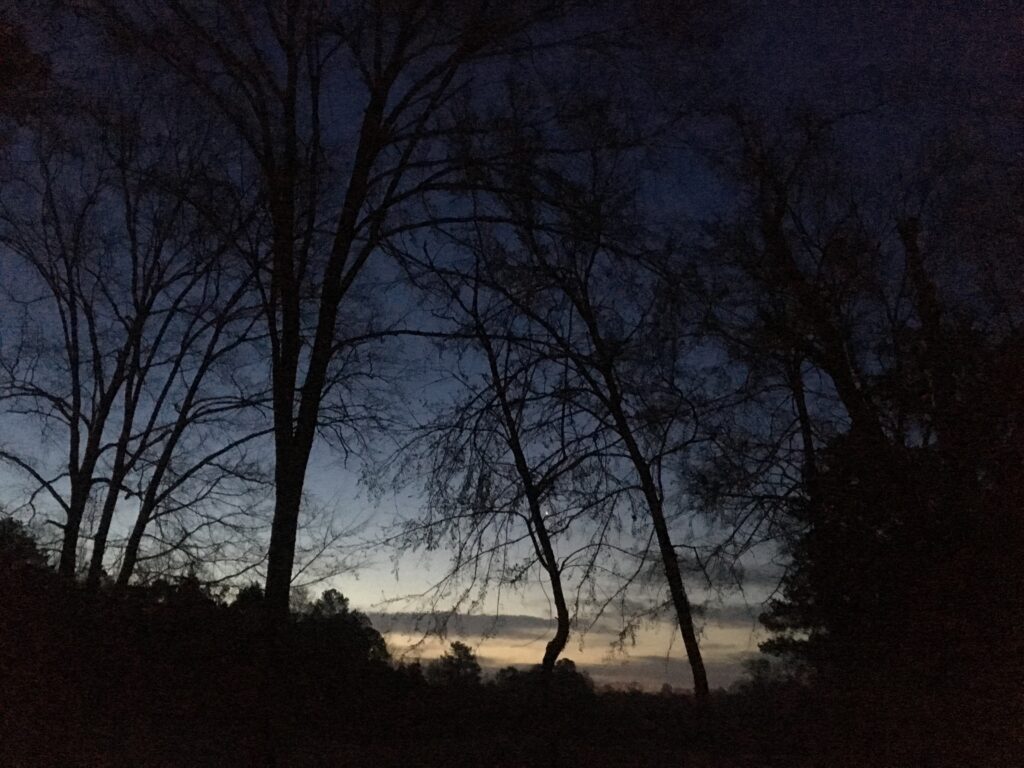

Pictures of the new place, taken by Renee Hovanec.

Aldo Leopold Description:

This spot is one that I often walked down to in my childhood. It is not far from the hustle and bustle of the city, yet once I descend from the street into the park, I am met with a different world entirely. A building or two occasionally poke through the trees, but they are easily forgotten as the brisk November air and the smell of damp leaves wash over me. Most of the fall color has left the trees, yet it persists in the leaves on the ground, which is speckled with infinite shades of yellows, browns, and reds. There is not generally much wildlife to encounter here. Deer will sometimes pass through, and I hear the occasional bird song, however, there is one exception. The squirrels are out and about, seeming to defy gravity as the leap from branch to branch. They scamper up, down, and across the trees, sometimes alone, but often in pairs, with one chasing the other, in what reminds me of my childhood games of tag. One began to chatter and screech when it saw me, but soon was distracted and continued about its acrobatic feats. Eventually, the squirrels moved on to a different part of the woods, and my place returned to a more serene state.

Mary Holland Comparison:

Both of my Phenology sites include water features, with extremely variable water levels. In Centennial Woods, the variability is caused by the rain, snowfall, and snowmelt. In Archibald Park there has been very little snow due to the warmer climate, but the small pond that accumulated was due to the increased rainfall. While in Centennial, the water flows over rocks, around boulders, and under branches, the water in Archibald is perfectly still. Both places are off the beaten path, and are inhabited by small rodents: chipmunks in the former, and squirrels in the latter. By this point in the year, most of the leaves have also fallen from trees in both sites, though those in Archibald Park have more recently fallen than in Centennial Woods. Take a moment to listen and the occasional bird chirps will become clear. Each site has different species of birds, but both have fewer than they’ve had in the past few months due to many migrating South for the winter. One species they have in common, though, is the Pileated Woodpecker. They are very rare in Archibald Park and the surrounding metropolitan area, but occasionally their distinctive pecking can be heard to the delight of those who know its origin.