Final visit to Casavant!

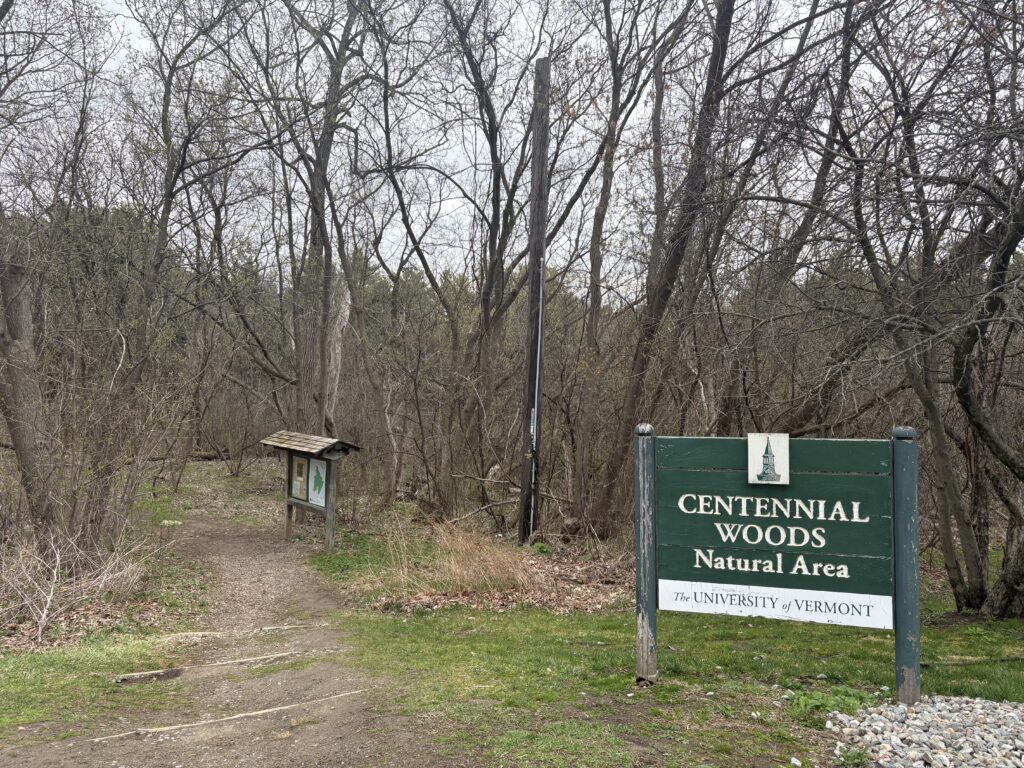

While Casavant was not my phenology site in the fall/early winter, I have definitely watched it change through the seasons. The transition from winter to spring is a beautiful phenomenon and there is no other place I’d have chosen to observe it in real time.

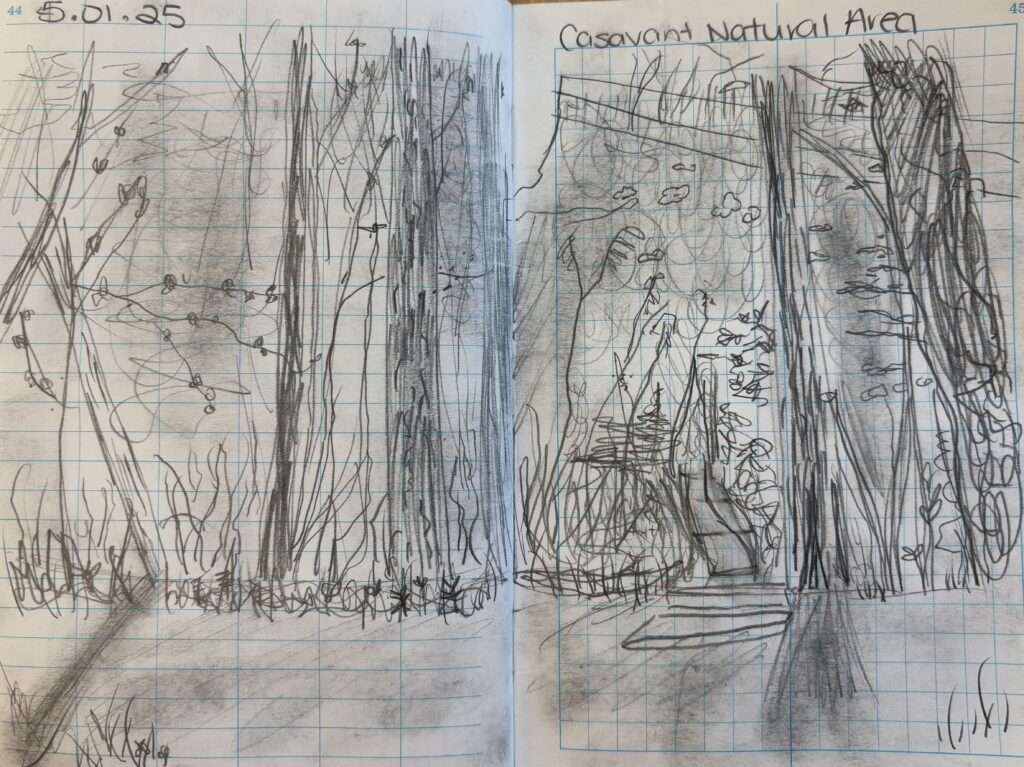

Sit & Sketch

Changing Seasons

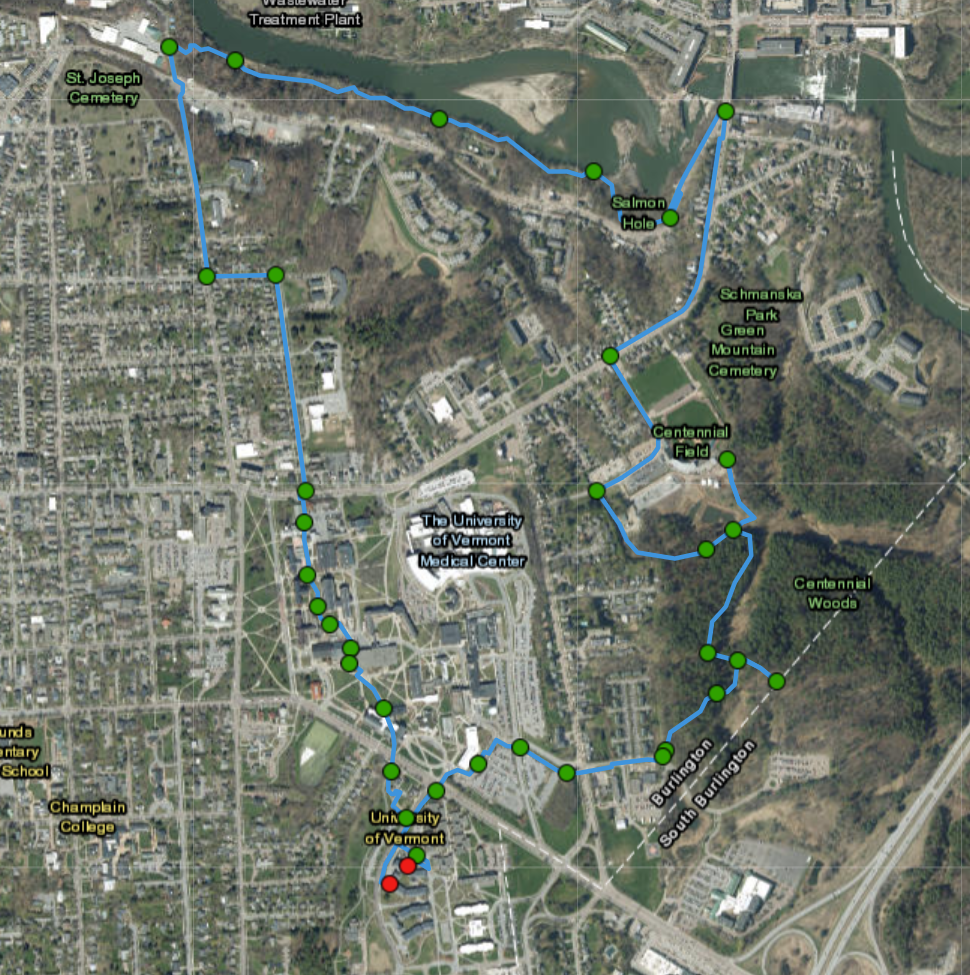

I’ve visited Casavant 3 times this semester in total, with different phenophases being expressed during each visit. Once in January, once in March and once in May. During my trip in January, it was very cold and I didn’t make it far down the trail. In March (for lab), I walked all the way down to where the natural area bordered the Winooski River. This last visit, I walked the entire loop. I am very excited to see how the park changes over the course of summer.

The most visible changes from my first to last visit is the melting of snow and regrowth of groundcover. Ferns, flowering species, grasses and other understory species are flourishing. Most trees have began budding, but only a quarter of the buds have broken and began growing new leaves.

Landmarks

Casavant has some distinct, defining features which I have come to love. The most prominent are the powerlines which span over a portion of the park, the large wetlands which the trails perimeter, the Winooski River bank and the rocky outcrop.

The more minor features are the numerous culverts and access points, the brook which drains into the wetlands and the numerous flooded areas with small bridges.

Socio-ecological Connotations

The natural area is shaped by both the natural world and urban development. Casavant Natural Area is borders the most urbanized areas in Vermont. Winooski to the north, the airport to the east, and Burlington to the southwest, the area is surrounded by developed land.

Before E Allen St. and I-89, the Winooski River shaped the land. Casavant consists of floodplain forests and vernal ponds, supplied by the Winooski’s intermittent flooding. The hiking trails run through the area’s more wooded, higher elevations.

Human intervention through the construction of roads, culverts, powerlines and housing has shaped the land to how we know it today. Culverts have eroded small valleys in the land as water drains from the roads above and large sewage access pipes jut out of the trailhead. I-89 borders 2/3 of the park and in combination with the airport, introduces significant noise pollution.

Located within Winooski, VT– a town named after the river, winoskik, Casavant offers a small representation of land stewardship and the human-nature connection, heavily emphasized in the indigenous Abenaki peoples culture. The “Onion River” flows through Casavant with little blockage among the banks on either side. As I visit this site, I remain conscious of the past land stewardship of the Abenaki and the gratitude I feel to those who came before me. While the land may only look a fraction as beautiful as it once did, it remains natural thanks to the Indigenous culture deeply rooted in the land’s history.

“Do you consider yourself a part of your place?”

I don’t usually directly insert the questions asked for these assignments into my blog, but I feel like this question deserves a section. Short answer: no, long answer:….

I do not feel as though I am a part of my place in the way that the mourning doves or the ferns are a part of the place. I do not feel like I contribute to the land as the streams and ponds do. I feel like a part of Casavant in the way I leave footprints like every other visitor or move sticks into the puddles to make makeshift paths. My mark is visible, if you look with intention, yet no one would know I had gone unless told. The park exists without me, but the trails do not exist without people. I do not consider myself a part of the place as an individual, as I have not contributed anything to the land other than gratitude, but I would consider myself as a collective, as the broader community of humans a part of the area.

While I did not highlight all the species I photographed at Casavant during this trip, I did upload them to iNaturalist, so if you are curious about those, you can find them here.