In Fall 2020, the Roy Rozenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University launched a new podcast on consular history called “Consolation Prize.” The host and executive producer is Prof. Abby Mullen, an expert on the Barbary Wars. When they were originally recording, I had a nasty case of laryngitis, so my work was quoted in Episode 1, but I did not directly participate. Fortunately, my voice eventually came back, and Abby and I were able to do an interview. That’s available as Bonus Episode 1: What Is a Consul, Anyway? Check out all the episodes in this awesome series! You can listen, or you can read transcripts on the web. The first series is focused on US consuls during the Early Republic, but they have exciting plans for discussing other time periods and foreign consuls in upcoming series!

Category: Presentations

OAH Panel on Digital History and the State

In April 2018, I had the pleasure of being on a panel on “Reinterpreting the American State: Digital History’s Intervention” at the Organization of American Historians annual conference. Cameron Blevins organized the session and presented some of his work on the postal service, and our other two presenters were Jamie Pietruska, working on meteorological data collection, and Benjamin Hoy, working on the Canadian presence at the border with the United States. Our commentators were Susan Schulten and Gregory Downs.

My presentation included praise for the process of iterative mapping, as I showed some of the maps I have made for previous presentations.

On the subject of the state, I concluded:

I haven’t yet made up my mind if the lack of knowledge at the center was a help or a hindrance to the daily operation of the US Consular Service. Certainly, some might see it as evidence of a “weak” state. I lean toward the idea that the vacuum at the center allowed for officials to adapt to what was most effective in their local circumstances, thus more effectively projecting US sovereignty abroad.

Looking for the National Dream

Ulf Brunnbauer and Ursula Prutsch very kindly invited me to present a paper at the conference they organized on “Looking for the National Dream: Austro-Hungarian Migrants in the Americas in Comparative Perspectives,” held at the Center for Advanced Studies at LMU-Munich in July 2017.

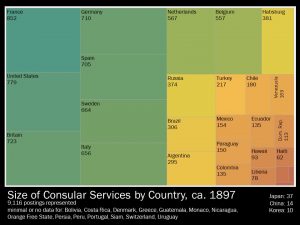

I presented on “The Habsburg Consular Service in Comparative Perspective,” using data from the US National Archives that surveyed global consular services in 1897 and select consular services in 1907, as well as the listings of foreign consuls in the United States published annually in the Register of the Department of State. (Thanks to Natalie Coffman and Kiara Day for their assistance with data entry!) I argued that the Habsburg government did not opt to use their consular service to the extent that most other European governments did, though they were in the process of a significant expansion when World War I began in 1914.

US and European governments used the flexible institution that was the consular service in a variety of ways, but one key use was to maintain ties with migrants living and working abroad. In that sense, the Italian consular service was the most active, and the Habsburg service was headed in that direction in 1914. I pointed out that there were many reasons for not having a large consular service; in particular, because most consular officials worked for fees rather than salaries, they were difficult to control and hold to professional standards. Here’s a comparison of the Italian and Habsburg services in the United States in 1907:

The Habsburg government’s consular presence in the US was slightly higher than average, but well below most large European countries. (Russia’s service was smaller.) For much of the late nineteenth century, the Swedes had the largest US presence:

I gave a similar presentation at the 2018 Austrian Studies Association annual conference held in Burlington, Vermont.

SHAFR panel on Aid and Emotions

At the 2017 SHAFR conference, I participated in a panel entitled “The Gift of Giving? Aid and Emotion in U.S. Foreign Relations,” which united alumni of the 2012 SHAFR Summer Institute, including Institute organizers Frank Costigliola and Andy Rotter. My co-panelists included Shaul Mitelpunkt, Elisabeth Piller, and David Greenstein, and our commentator was Barbara Keys.

My contribution was titled “’The sympathies of the Consul are strongly aroused’: Contemplating US Consuls’ Out-of-pocket Aid to Americans in Distress Abroad in 1902,” and it was based on responses to a survey that the State Department conducted in early 1903. Unlike the governments of many other states, including the Great Powers, the US government did not have a public fund for assisting the return to the United States of Americans who fell into financial destitution abroad, or for short-term relief of such people. A few consuls in larger cities with significant numbers of Americans could call on private American aid societies to offer such assistance, but most consuls had to pay out of their own pocket. If they refused to pay, they risked criticism from their local hosts and the press back home.

In their responses to the survey, consuls expressed a wide variety of emotions, but frustration was perhaps the most frequently in evidence. Consuls were annoyed with the large numbers of people who came to ask for help, disrupting the routine of the office. Many who asked for help were professional fraudsters, and consuls were frustrated when they were conned, though most seemed to take that as par for the course. “Tramps” came in for particular opprobrium, and consuls expressed a range of reactions, from those who always gave tramps money to get them moving out of the district to those who refused all requests and made statements that expressed deeply held class prejudices.

I am working on an article based on this material. And since I can’t do a post without a visualization, here’s another work in progress coming out of these records: consulates with typewriters in 1903.

AHA 2017: Making Digital History Work

At the American Historical Association conference held in Denver in January 2017, I participated in a panel on “Making Digital History Work,” which dealt with challenges of digital projects, especially outside of large-scale, well-funded collaborative projects. Our chair and commentator was Dr. Seth Denbo, the director of scholarly communication and digital initiatives for the AHA, and the other panelists were Dr. Konstantin Dierks of Indiana University, who spoke about the challenges for mid-career historians in learning the myriad skills required for digital projects, and Dr. Fred Gibbs of the University of New Mexico, who stressed the value of failure in constructing digital history projects and the importance of individuals understanding not only the historical content of their projects, but the technical aspects as well.

I showed this website as a form of digital history emphasizing process, small steps, and the value of iterative mapping. I also passed along six tips about building a dataset, based on my experiences to date:

Be prepared to start over. It’s probably better to use Excel than a database program, at least as first, as it is more flexible.

Keep a log or journal that reflects where your information has come from, the notes about the organization of your database (such as what your column headings mean), and where you have saved relevant files.

Use “save as” liberally so you can go back to earlier versions if you make a mistake or otherwise go down the wrong path.

Atomize your data and then concatenate as needed. It’s easier to put pieces of data together than it is to separate it.

If you’re using Excel and you’re unfamiliar with the “vertical lookup” function (VLOOKUP), you should learn that function.

Practice in other venues, like Zotero, iTunes, your grade book, or other administrative tasks. Doing so will help you get a sense of how data needs to be organized to achieve the desired ends.

Transimperial US History

In May 2016, I had the very good fortune to participate in a conference on Transimperial US History at the Rothermere American Institute at Oxford University. Hosted by 2015-16 Harmsworth Professor of American History Kristin Hoganson and Rothermere director Prof. Jay Sexton, the conference brought together an exciting group of historians and historically minded scholars considering the relationship among Americans, the US government, and “the imperial” in the long nineteenth century, as well as the ways in which “the United States” was and was not unique when compared with other contemporary powers.

My presentation ended up being my first attempt to work through a comparison of most of the world’s consular services in 1897. I found a box at NARA with reports on those services done by DOS personnel, and I’ve been working on creating a dataset from those materials. There is still a lot of interpretive work to do, but one thing they reveal is the relatively large size of most countries’ services. It’s not just the Great Powers that have large services, but neutral powers as well:

Although the United States certainly had a large service, I’m rethinking how it relates to the services around the world, since the data indicates that the US service is on par with those of other countries, at least if we’re using number of posts as the measure. In the presentation, I shied away from my proposed title about the US Consular Service as the “colonial office of US informal empire.” I still think there’s something extremely useful there, but I’m still thinking through exactly what that is.

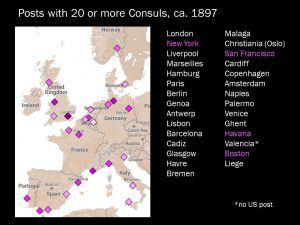

The data also shows us which cities were full of consuls from all over the world:

The data also indicates places that were not full of consuls, but rather hosted a single government’s representative, indicating a bilateral relationship. I’ll be focusing on that aspect as I continue to work with the data.

Many thanks to Kristin, Jay, the Rothermere staff, and the conference participants for a fantastic experience!

Digital Humanities at UVM

My colleague Melanie Gustafson and I presented some of our work as part of the series of events at UVM organized by our Humanities Center Collaborative Faculty Fellowship Group on the Digital Humanities. Thanks to all who attended!

I showed some of the maps and visualizations I have made as part of my research on the Consular Service. (You can see them as part of my 2015 SHAFR presentation.)

Prof. Gustafson and I both stressed the time commitment involved in digital humanities projects, the need to work collaboratively to bring all the essential skills to the table, and the intellectual work of categorization and organization. We agreed that, not only do digital humanities exhibits/projects need to be considered as part of departmental promotion and tenure guidelines, but properly curated datasets made available to the public should be counted as well.

Presentation: FRS 2015

I was fortunate to kick off the UVM History Department’s Faculty Research Seminar series yesterday, sharing a presentation on “Bureaucracy and Humanity: Exploring the Records of the US Consular Service” with terrific colleagues and graduate students. I resisted providing an actual title until the last possible moment — the start of the presentation — but my advertising blurb promised “tales of fraud and death, bureaucratic grandeur, and State Department attempts at art, plus a new gadget.” I won’t put the whole thing up here, but here are some highlights, minus most of the analytical bits:

THE NEW GADGET: The ScanSnap SV600 Contactless Scanner, which was what caught my eye in terms of new technology when I was at Archives II in College Park this summer. I’m looking forward to really using it when I return this fall, but so far, so awesome.

BUREAUCRATIC GRANDEUR: Members of Congress, the public, and some central office personnel at the Department of State certainly had lots of suggestions about how to improve the US Consular Service, but a lot of ideas came from consuls themselves. After the creation of inspectors — holding the title Consuls General At Large — in 1906, there were more and grander suggestions, most aimed at improving efficiency and uniformity of practice. Many of the ideas were very much in line with contemporary efforts for Taylorist or similar reforms of business processes. Most were deemed impracticable — or even “revolutionary” — by the central office, but they did push through a reform that required US consulates throughout the world to be open to the public from 9 am to 4:30 pm Monday through Friday and from 9 am to 1 pm on Saturdays. The discussion began in 1913 after one of the At Larges expressed his dismay that the consulate at Riga was only open from 10 to 3. The central office solicited opinions from the rest of the At Larges, who split on the issue: some thought local customs and the discretion of individual consuls should prevail, while others emphasized the need to match the norm in the United States and thus accommodate the expectations of members of the American public traveling abroad. The central office went for the latter position and sent rather harshly worded instructions to specific consuls to conform with the new rules. I’m not sure (yet?) how effective the reform was, especially because it was done in 1916 in the midst of World War I — the very definition of “extenuating circumstances” — but the documents clearly evidence the frustrations of all parties.

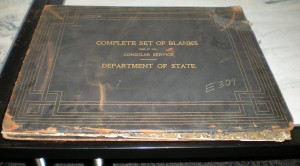

STATE DEPARTMENT ATTEMPTS AT ART: There was a visualization — poorly photographed on my part — of one of the reform plans, plus an At Large’s drawing of what a proper US Consular Agency office should look like. But my personal favorite still remains the oversize scrapbooks of consular forms assembled for as yet unknown reasons in approximately 1890:

Sadly, even though they promise a “Complete Set of Blanks” — and, thus, potentially, an expression of all of the service’s bureaucratic functions — it isn’t actually complete. There is quite a bit in there, however, though they definitely don’t deserve points for effective or aesthetically pleasing use of space.

DEATH: When an American died abroad, consuls were responsible for reporting the death to the State Department and ensuring the proper handling of the body and the deceased estate/personal property. I showed some examples of the reports generated by consuls stationed in England in 1913; they’re especially easy to find for the Decimal File years (1910-29; see this post for more information). They could be useful sources for scholars interested in a variety of historical subfields, as they provide information about citizenship, the circumstances of death, familial relations, travel patterns, and mortuary practices, among other things. I was struck by the number of women evident in the records. There’s a lot of very raw emotion in there, too.

FRAUD: Consuls also worked to protect US citizens from various kinds of fraud. In Anglo-American relations, a great deal of time was spent attempting by various means to communicate to Americans that “THERE ARE NO GREAT UNCLAIMED ESTATES IN ENGLAND.” It was popular scam for people who claimed to be British attorneys to put advertisements in newspapers announcing that they were looking for the heirs to “the [insert common surname here] estate,” valued at however many millions of pounds. The victims of the fraud paid for copies of wills, attorneys fees, genealogical reports, and other things in pursuit of claims. Requests for assistance in furthering the claims or establishing the legitimacy of the advertisements came to the legation and consular staff so often that, in 1884, they had a form cover letter and a circular printed to send in response. (And still in use in 1914.) While many circulars I have seen are quite tactful, this one isn’t; if nothing else, the ones I’ve read before have been addressed to specific members of Congress, while this began as internal State Department communications. You can view the original on pages 224-29 in the 1884 volume of Foreign Relations of the United States here.

Presentation: SHAFR 2015

For the 2015 Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations (SHAFR) conference, I organized a panel on “Patterns and Problems: The US Consular Service in the Nineteenth Century.” Joining me in presenting papers were Prof. Lawrence Peskin of the Morgan State University, who spoke about his research on the Montgomery family, a trading family who provided the US consul in Alicante, Spain from 1793 to 1823; and Prof. Mattew Raffety of the University of Redlands, who spoke about Nicholas Trist’s time as a – very loquacious – US consul in Havana between 1831 and 1845. Our chair was Prof. Nancy Shoemaker of the University of Connecticut, and our commentator was Prof. Kristin Hoganson of the University of Illinois.

Here’s my paper on “Charting the US Consular Service in the Long Nineteenth Century”: