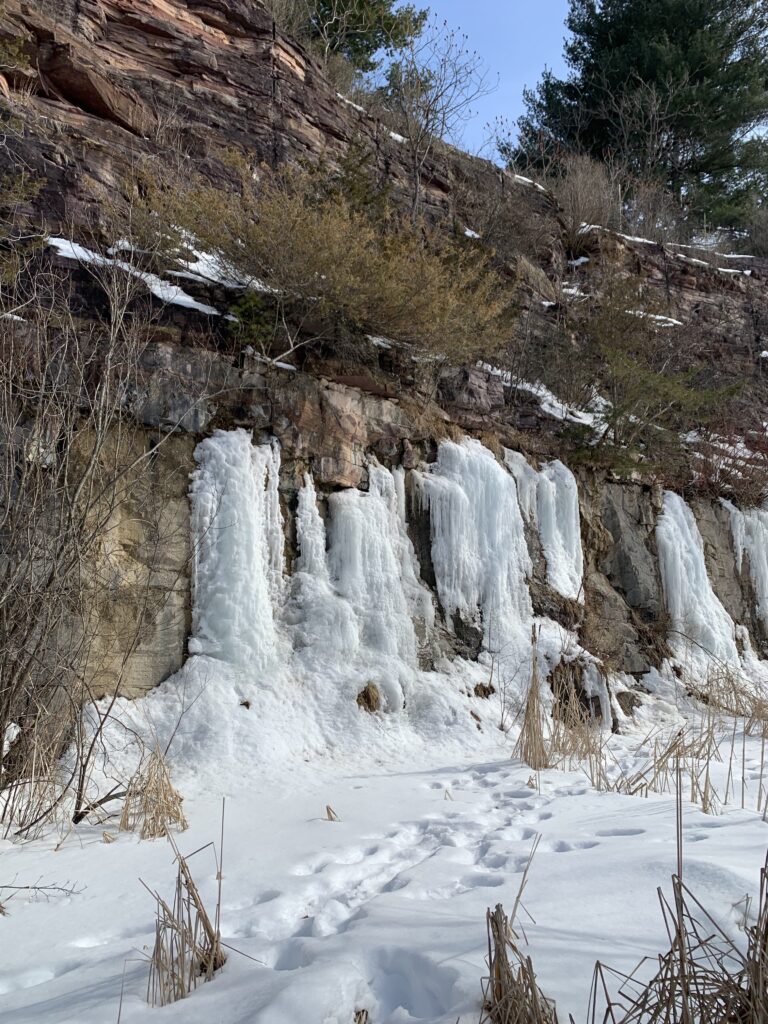

…in which Vermont faked us all out and gave us hope for spring. Don’t be fooled, the sun still set at like 5 pm.

On the fine Sunday afternoon that I most recently visited Redstone Quarry, Vermont was experiencing our first false spring. It was a balmy forty degrees, the sun was shining, and the air smelled fresh. I have observed from years of living in the Burlington area that we’ll have a few gorgeous days in February and March each, just warm enough to trick us—and the wildlife—into believing that spring may have come early. Out of all the birds that were singing that day, the only song I recognized was the notorious chicka-dee-dee-dee of the black-capped chickadee.

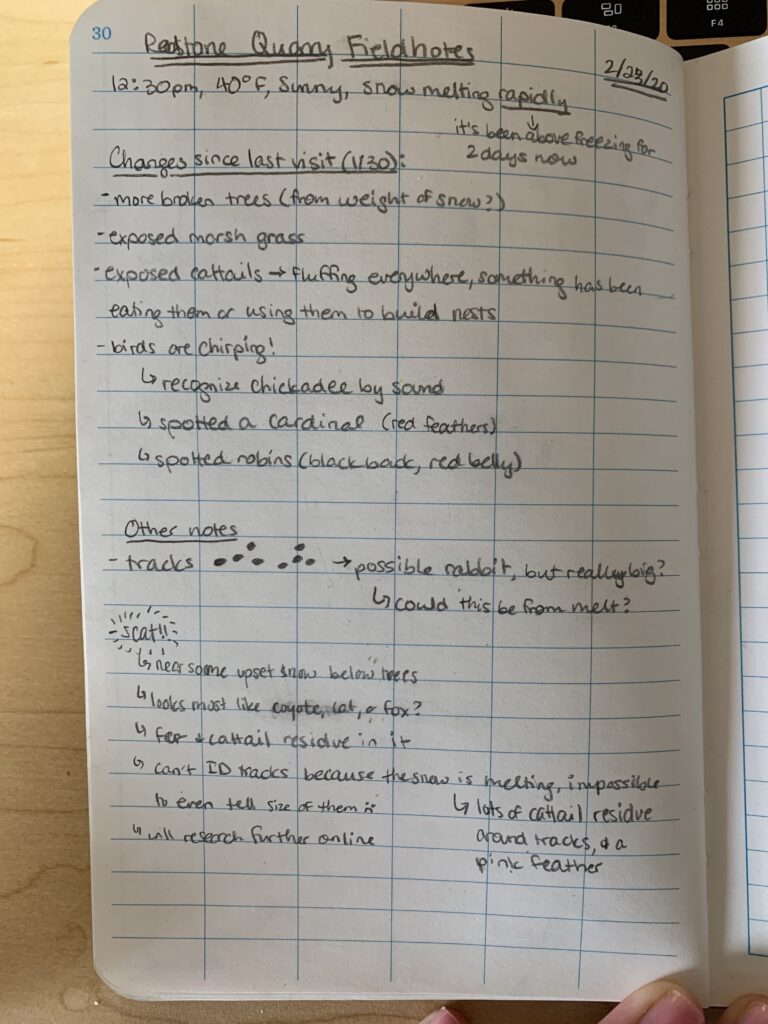

Two weeks before this visit, we’d had a major snowfall, which was inconveniently melting. It was incredibly challenging to document any animal tracks in the snow, given its half-frozen, half-puddle, overall mushy quality. We found what we theorized to be rabbit tracks, since they were in the “hopping” pattern and diagonal. (Levine, 2014). They were much larger than typical cottontail rabbit or even snowshoe hare tracks, but we assume that is due to the fact that the tracks were probably made before the snow started melting. (Figure 1). Note also the faint squirrel tracks in the background of the photo.

Another exciting discovery was scat. Upon close inspection (but not that close, ‘cause germs), it had some dark fur in it and possibly some cattail fluff. (Figure 2). Since most animals mentioned in this month’s chapter of Naturally Curious avoid cattails unless food is really scarce, we used this to reason that it’s been a rough winter for some of the local animals. The closest match from the Mammal Tracks and Scat pocket guide was gray fox (if it were a red fox, the urine would have smelled like skunk). (Levine, 2014). However, this is a highly recreational area for dog-walkers and also very close to a neighborhood, so there is a chance the scat was from a domestic dog or cat. The accompanying tracks were indistinguishable in the snow, due to the ongoing melt.

Right before leaving the site for the day, I came across a gray squirrel. I identified it based on its coloring, and the fact that its nest was in a deciduous tree. Grey squirrels build their nests out of twigs and leaves, very high up in trees. (Holland, 2019). Unfortunately, in my excitement of recording a video of the squirrel leaping along the wall of Monkton Quartzite that makes up Redstone Quarry, I failed to document the nest.

Grey squirrels feed mostly on seeds and nuts from trees such as oak and beech, both of which are present at this site. They forage for food and hide it in caches around their home range, which they find later based on smell and memory. (Lawniczak, 2002). Unfortunately, a lot of animals prey on squirrels, especially weasels, red foxes, and hawks, but they are hard to catch because they use trees and understory for cover and can hop quickly in and out of hiding places. (Lawniczak, 2002). The squirrel I documented may have been running from a predator, foraging, and/or picking up more oak leaves (identified by shape) for its nest.

I look forward to my next visit, when spring has come for real, so I can explore the area further. My goal is to find squirrel caches, and maybe even a den for whatever animal left that scat!

Literature Cited

Holland, M. (2019). Naturally curious: a photographic field guide and month-by-month journey through the fields, woods, and marshes of New England. North Pomfret, Vermont.: Trafalgar Square Books.

Lawniczak, M. K. (2002). Sciurus carolinensis (eastern gray squirrel). Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Sciurus_carolinensis/

Levine, L., & Mitchell, M. (2014). Mammal tracks and scat: life-size tracking guide. East Dummerston, VT: Heartwood Press.