As part of my research I examined 8 scholarly articles in detail, examining the varying claims about gendered spaces within the home and the ways these gendered landscapes impacted children. Authors such as Blunt (2005), Witt (1997) and Bowlby (1997) discuss the home as the primary space in which identities are formed and from this they are projected into the public realm. Each of these authors discusses explicitly the role of gender within the home in determining the identities that boys and girls form. For example, the supposed role of women in the domestic space influences girls that grow up around this, reinforcing gender roles among their peers. Gagen (2000) discusses this at length, studying the differing play practices among boys and girls and developing understandings of the ways in which home life may impact this. Gagen (2000; 610) notes that girls were encouraged more so to ‘contain within their evolutionary history…instinct to care, procreate, and keep home.’ Following this, Gagen (2000) explains that these expectations were carried into the play practices of girls, who were often encouraged to engage in play activities that involved tea parties and looking after younger children. Witt (1997) offers further discussion of the reinforcement of gender roles, labelling the home as the primary space in which children learn attitudes and behaviours to gender roles. This, she argues, is then reinforced by peers as children enter school, involving themselves in the types of play practices discussed by Gagen (2000). Witt (1997) also finds that pre-school children whose mothers work outside the home experience the world with a view that everyone in the family has access to the outside world and that they grow to understand they can make choices in life in which their gender does not hinder them. The idea of gender roles as representing a hinderance offers a crucial point of view, as it is clear that the gender roles seen in the home influence children’s understandings of their capabilities. The ways in which the writings of Gagen (2000) and Witt (1997) intertwine with each other hint at a recurring theme throughout the literature; children will extrapolate and apply their experiences of the home to their experiences of public spaces.

Also linked to the capabilities of each gender is the work of Valentine (1997) who discusses how the attitudes of parents towards boys’ and girls’ respective vulnerabilities in public space vary. It is argued that for parents, the ability of their children to navigate public space is dependant upon their gender, and that girls are more capable than boys. Valentine (1997) argues that girls appear to be more capable of navigating public space safely than boys because they are thought to have greater self awareness and sexual-maturity than boys who are seen as more irrational and irresponsible. These findings offer a contrast to what is generally discussed within the literature, suggesting in fact that boys, who are traditionally seen as more adventurous than girls are not as capable in public space. In this way, Valentine (1997) offers a counter-narrative, suggesting perhaps that in some instances the gender roles of their parents do not apply to the childs ability to navigate public space. Like much of this literature, Valentine’s (1997) idea’s are countered by the work of Simmons (2015) who discusses the lives of young black girls in New Orleans. In Simmons’ (2015) account, the accessibility of public space is severely limited for girls, quite different from the observations of Valentine (1997). Through examining this I was able to understand the ways in which attitudes may have changed over time, alluding to themes of race, class and segregation. In this sense, the experiences of children in public space was dependent upon the period of time and the social aspects that existed at different times.

Simmons (2015) is explored in more depth here:

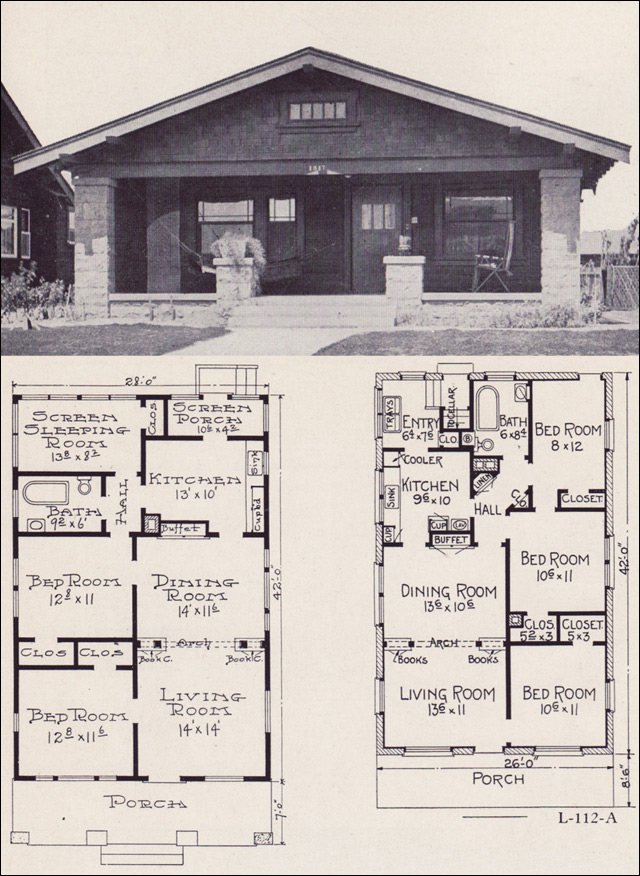

Munro and Madigan (1999) and Llewellyn (2004) discuss the physical layout of homes and the ways in which this can reinforce gender roles. Llewellyn (2004) claims that in home design and architecture the kitchen is considered the ‘workshop of woman, and the arena in which most of the problems were found.’ Munro and Madigan (1999) add to this, suggesting certain styles of housing reflect the ideals of a bourgeois family with strict boundaries between public and private, masculine and feminine. They also attempt to understand how families ‘negotiate their relationships within the limitations imposed by the physical space of a conventional suburban home.’ This focus on the phycial layout of the home suggests that gendered landscapes of the home are not just a social construct but are ingrained into the structure of the home. The image below corresponds to this research, showing a typical layout of a home. Note the kitchen (female space) toward the back of the house.

It is clear that within academia the home is considered one of the most prominent spaces in which the lives of children are influenced, alongside the breadth of literature discussing the home as a gendered space, I am able to infer that gendered landscapes of the home are a major influence on the lives of children. While some of the literature shares similarities and differences, the experiences of children appear to be very much determined by their parents and consequently the homes they grew up in. Because of the gender roles of the period of history being examined, it is clear that patriarchal ideas were rife and as a result the lives of children were greatly impacted, impacting areas of their lives such as school, peer relations, play practices, accessibility to public space and perhps most importantly, their perceptions of gender as they progress into adulthood.