Rites of Passage

How Constructions and Experiences of Childhood are Related to Broader Social, Economic, and Political Contexts

Rites of Passage for Native American Children in the Boarding School Era

Exploring rites of passage through the experience of Native American children at and around the turn of the 20th century is an intricate opportunity to make sense of how ‘childhood’ was constructed in a way that was highly dependent on time, place, and broader social context. Themes of racism, politics, and authority are at the forefront of the boarding school era, its associated legislation, and the overall moment of shifting paradigms for Native children from the mid 1800s to mid 1900s. In white society’s eyes, Native American adults were seen as eternal children and as inherently lacking certain elements of civility, character, and ethics compared to white adults. This racist and baseless understanding of Native Americans contributed to a broader justification of their legal, social, and cultural oppression in the United States. Native American children were viewed in a slightly different way. While they too were perceived to have biological shortcomings, there was a belief in the potential for them to be saved, reeducated, and shaped into productive members of Euro-American society. Legislation about Native parental and child rights, specifically as it regards education as seen in the boarding school era, can be analyzed as it is represented here — in a non-comprehensive but chronological order — to make sense of rites of passage for Native American children. Many of these rites of passage came in the way of cultural re/education, in physical development, specifically regarding health and hygiene in boarding schools, and in child legal rights as legislated by the Department of the Interior.

Explore the link below for a timeline regarding rites of passage for Native American children.

Timeline: Rites of Passage for Native American Children

Constructions and Experiences of Childhood in the Jim Crow Era

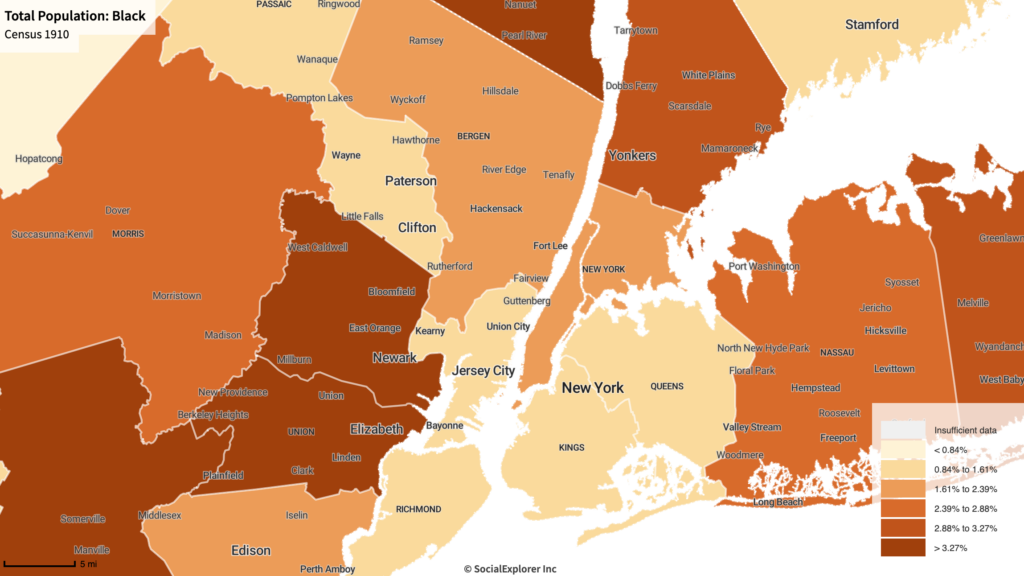

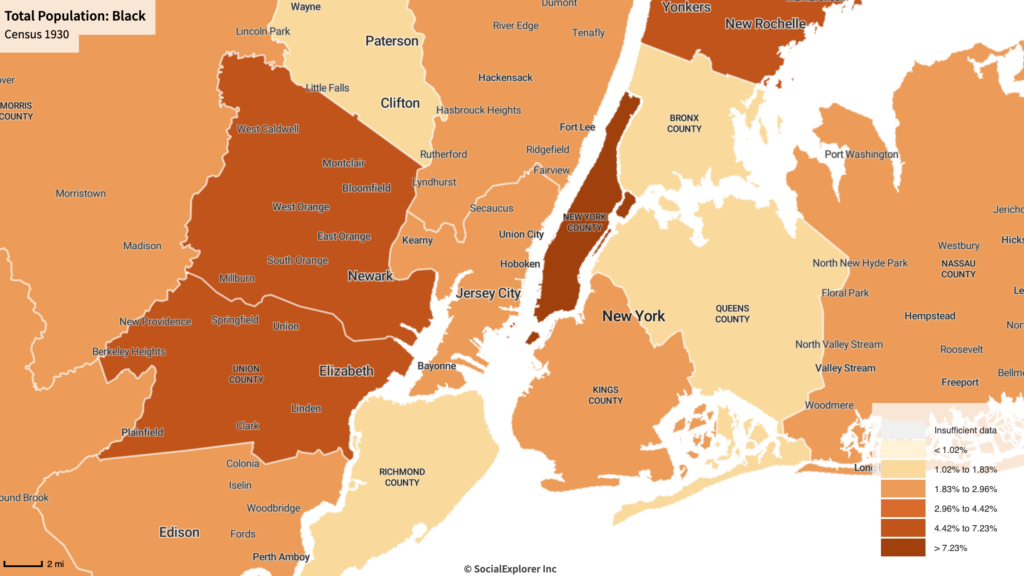

The Jim Crow era and the subsequent Great Migration had deep effects on the lives of millions of Americans who sought to find refuge in a society organized by overt discrimination. As Black people fled the South and overt discrimination, they were then met with discrimination in the North as unwelcome newcomers. The effects of this era can still be seen today and due to the all encompassing nature of racism in the U.S. (Wilkerson, 2010), we can see how the constructions and experiences of childhood were deeply connected to this institution. By looking first to evidence of the Great Migration and then to the experiences of children learning lessons of race in a later section, we will see how social contexts shaped race-based ‘rites of passage’ and created vastly different experiences for children on the basis of their race.

These maps demonstrate the growth in the Black population in New York City in the early 20th century, a direct result of the Great Migration. By seeing the vast increase in the population in New York, understanding that all Northern and Western cities also saw an influx of Black migrants, we can start to understand the level of Black flight from the South (Wilkerson, 2010). This provides the social context to the experiences of Black and white children in this era which will inform our discussion of lessons of race which can be see as a type of “rite of passage” in a later section.

The Diverse Experiences of ‘Childhood’ by Region, Race, Gender, and Class

Lessons of Race as Rites of Passage

This StoryMap presentation provides quotes from primary sources of lessons of race that children experienced in the early 20th century. These accounts come from both Black and white individuals from varying social classes which show the vast differences in experience based on these factors. By exploring the experiences of Black children, we can see varying experiences due to their class but in general, the lessons their parents had to teach them as they matured. This suggests a tension for parents between sheltering their children from race (often the case for white children and sometimes Black children) and ensuring their safety by teaching them the lessons their children would otherwise be taught– possibly through their own harm by other social actors. These accounts are disturbing, however they display the experiences of children who had to learn about race in a way which may provide a glimpse of the realities of racial oppression.

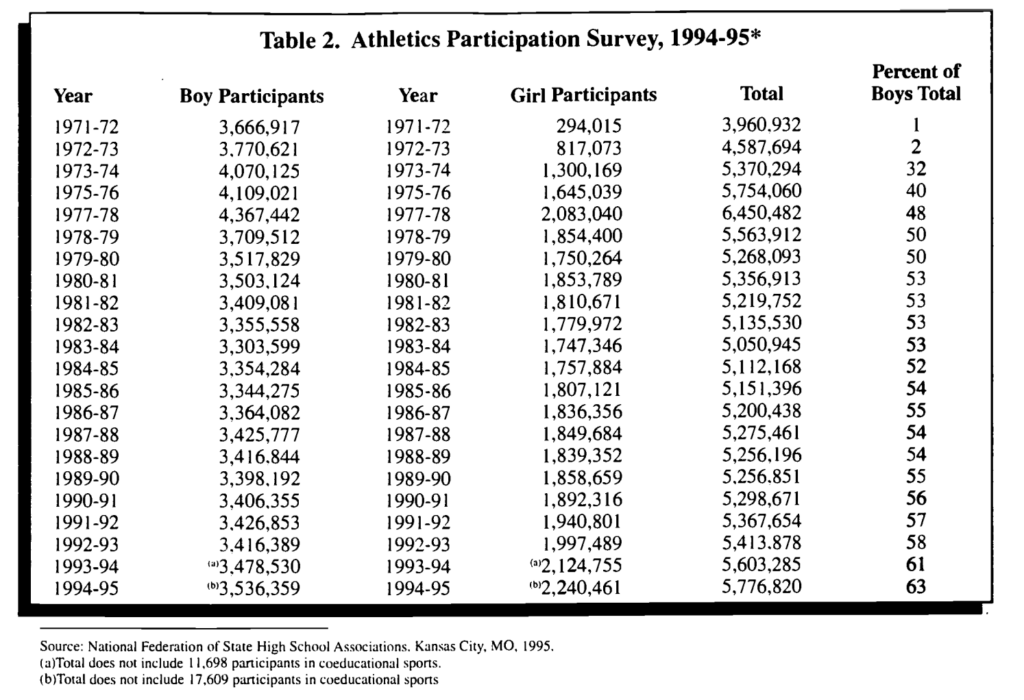

Youth Athletics as a Rite of Passage

Getting involved in youth athletics has become a staple of most American childhoods- but it hasn’t always been this way. This timeline serves to display not only the history of youth athletics in the United States, but the inequalities that were upheld by the institutions in charge of developing these organizations. It took years for girls to acquire equal rights to play, and even more for children of color.

This timeline of major ideas and developments for sports organizations demonstrates some of these key moments.

Material Culture in Relation to Childhood Rites of Passage

Toys, sports, and games were all used to aid children in maturing their way into adulthood, but in different ways. Aspects like place and gender, as discussed in the Story Map below, were both deciding factors on what toys children were given, and what games and sports they were encouraged to play. In general, the wording of archival sources made it clear that gender binaries and assumptions based on gender were both extremely prevalent throughout the 1800’s in the United States.

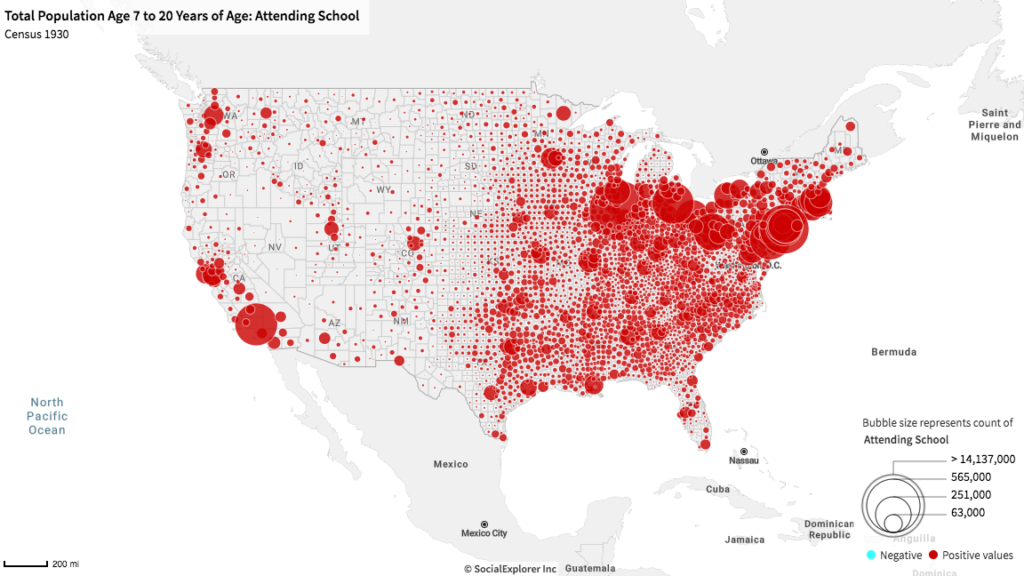

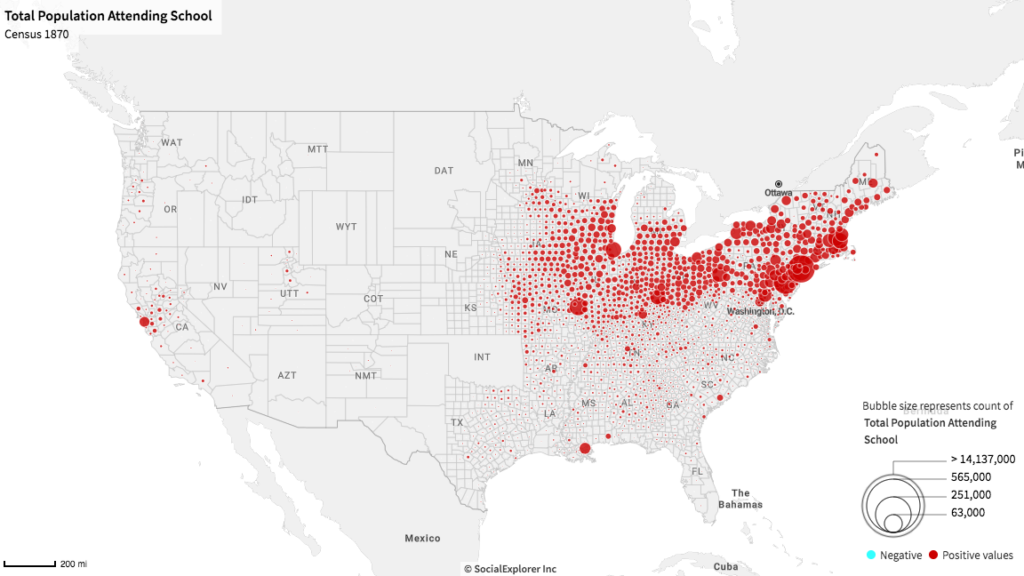

An Emerging Rite of Passage: Education

Although it has been established that children’s rites of passage depended greatly on a child’s race, gender, location and economic situation, the 20th century brought a new rite of passage that all children would achieve eventually: education. Today, all children are assumed to be in school, and the most productive, successful adults all achieved at minimum a high school level of education, but this has not always been the case. As shown in the map below displaying 1870 school enrollment census data, an alarmingly large number of children were not in school, especially in rural areas. If children weren’t in school, then they almost certainly were involved in some kind of work. As discussed in Professor Cope’s work, children living on farms almost always worked in the fields in some capacity, and children in urban areas were often employed by factories for wages (Cope, forthcoming). The chapter then explains how this culture changed, usually in tandem with compulsory schooling laws. As more areas of the country adopted these laws, along with minimum age requirements for employment laws, the student population skyrocketed, as displayed in the 1930 census data on school enrollment.

However, rural parts of the country were slower to adopt the new education movement. Data from the Children’s Bureau study on rural Texas in the early 1920s (Dart & Matthews, 1924) shows that the majority of children in certain counties were involved full-time in farm work, especially teenagers. Texas law only regulated children’s involvement in work for wages, and therefore did not apply to children working on family farms. Most of these farm-owning parents claimed that they needed the labor to get by, and “worked (their) children as soon as they were the least bit big enough”. Many were reluctant to subject their children to work, saying that “their work (was) a great drawback to their education” (Dart & Matthews, 1924). Although many rural Americans had adopted the pro-education stance that the rest of the country held, some were unable to afford losing the extra labor that their children offered. As the middle of the 20th century approached, more child labor and school attendance laws along with the advancement of farming and industry solidified education as a part of every child’s life. By the end of the WWII era, education was viewed as a vital rite of passage for children, in the opinion of both the general public and the federal government.