The notions behind summer vacation as a concept for American children were largely created by the processes of urbanization.

Avon (1999) credited the creation of the creation of the American vacation to the annual summer evacuation from East Coast cities to any that could afford it, which began in the nineteenth century. The migration from urban areas was due to the contemporary medical belief that diseases could be spread through “bad air;” which was perceived to be prevalent in a hot city. As the American middle class grew, they began adopting this tradition.

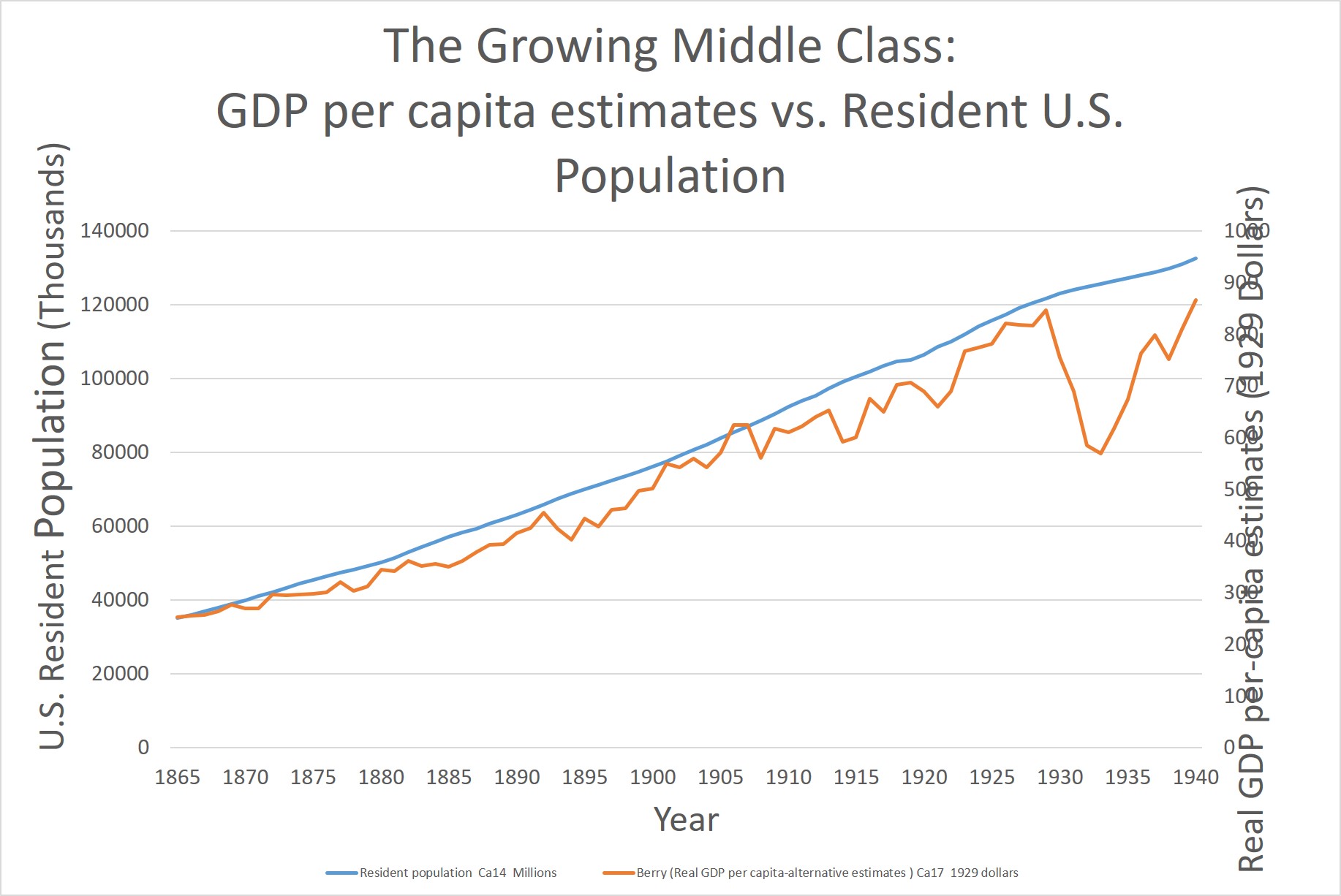

U.S. Resident Population vs. Domestic GDP (in 1922 dollars)

Nature as a concept became prevalent in the minds of Americans during the periods of industrialization throughout the nineteenth century. In his book, Back to Nature: The Arcadian Myth in American Society (1969), Peter J. Schmitt described how contemporary protestant fears of the immorality of the city shaped the belief that nature was the optimal site of moral rejuvenation. Julia Guarneri’s (2012) study of the Fresh Air Fund’s first fifty years, explores how the protestant views on nature’s restorative properties prompted the formation of the charity in 1877; which sent New York City’s tenement children on a two-week summer vacation to country homes. Guarneri argues the fund’s founders saw the trips as a means of “redeeming spiritually innocent and physically feeble children”, however, by the inter-war period the fund’s directors “used country trips to acculturate children to the nation’s growing middle class” (Guarneri, 2012, 30). This assessment supports Avon’s (1999) argument that the social practice of vacation became an integral part of the American middle class in the early twentieth century. Avon additionally argues that American adults felt anxious about time away from work, due to deep-seeded puritan values.

In his book, Schools In: a history of summer education in American Public Schools, Kenneth Gold explored how 19th and early 20th century education reformers’ ideas transformed the school calendar. He argued processes of urbanization shaped the reformers’ thoughts on a child’s need for a respite from schooling, and contemporary scholarly opinions of health promoted the notion that this break should be during the summer months: “summer was universally once an integral part of the urban school year with well-attended schools and substantive curricula. By the end of the [nineteenth] century, however, several factors brought about the demise of summer terms in these cities…. the removal of the summer from the urban school year stemmed from a powerful belief about the nature and frailty of the human mind and body” (Gold, 2012, 72). Gold’s assertion that the conditions of the human mind and body were of paramount concern to reformers coincides with Elizabeth Gagen’s writings on the rise of “scientific thinking” on child rearing. Gagen argued “scientific thinking” during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century increased a focus on the body as a site of one’s development. As she described it: “With the aid of emerging theories of physiological psychology, the transformation of individuals was reconceived as a process attainable via the muscular conditioning of consciousness”.(Gagen, 2004, 419-420).