Shoes and Education

As discussed in the literature review, poor children who lived in rural areas would have to walk to and from school, through woods and streams, and often without proper shoes or footwear (Hoffschwelle 1995). This would put children at risk for life-threatening infections and injuries (Hoffschwelle 1995).

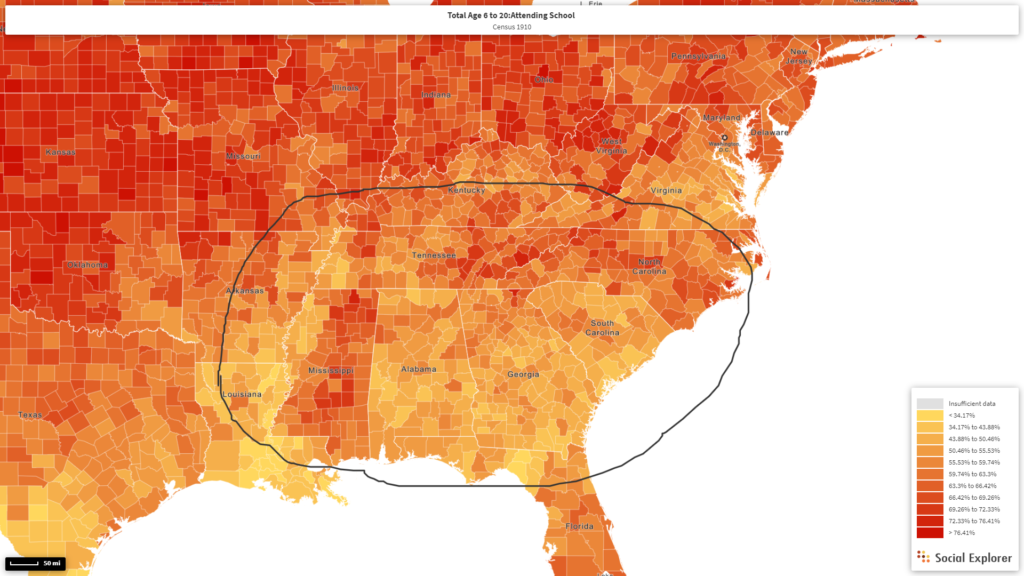

Children without shoes were at risk for infection even when they were at home or school. Poor sanitation facilities resulted in the poor containment of human fecal waste. As such, one major infection that affected school-children – and adults – in poor areas of the rural south was hookworm. It is estimated that 40% of school-aged children in the American south were infected with hookworm in 1910 (The Rockefeller Foundation).

Hookworm is a parastie that lives in the small intestine, but is transmitted through soil – usually found in fertilizer or in areas where fecal waste is poorly stored (Center for Disease Control).

The most serious effects of hookworm infection are anemia and protien deficiency due to blood loss, and children who are repeatedly infected by hookworm can experience a retardation of growth and mental development due to the loss of iron and protien (Center for Disease Control). However, the more common symptoms of infection are lethargy, bloated stomach and other digestive problems (Rockefeller Foundation).

Rural areas in the south with high hookworm infection rates had correlating low school-attendence, enrollment and literacy rates.

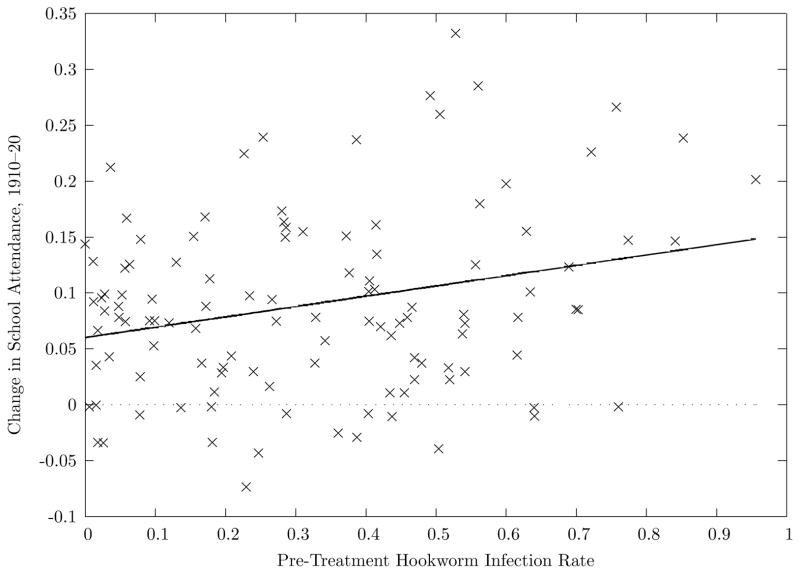

Efforts to treat the epidemic began in 1910, with a focus on distributing deworming medications and spreading education on good hygiene practices to avoid contracting worms (Bleakley).

The Rockefeller Sanitary Commision, funded by John D. Rockefeller, played a large role in the eradication of hookworm during this period (Bleakley). One of the materials they distributed was a children’s book called “The Story of A Boy,” by B. Stephany. The book focused on a young boy infected with hookworm, and served as a cautionary tale to children about the dangers of going barefoot around out-houses or other areas where human fecal matter was in contact with soil (Rockefeller Foundation).

The period after hookworm school enrollment, regular school attendance and literacy increased dramatically in areas that had previously suffered from high rates of hookworm infection (Bleakley).

These types of issues were exacerbated for people of color living in rural southern areas during Jim Crow – even when reforms were being introduced (Holley 2001). The implicit biases local governments had against people of color living in their communities were reflected in the fact that “colored” schools were given little or funding, leaving it up to the teachers at these schools to find solutions to education inequality (Holley 2001).

Shoes and Material Culture

Material Culture and Health

In addition to being material objects, shoes have played a particularly interesting role in American material culture. A rise in “scientific parenting” at the turn of the 19th century that in which mothers placed their trust in doctors and other child “experts” (Bates 1997), there was also a rise in children’s products marketed toward mothers with the intention of assisting them in raising the “ideal” child (Jacobson 2004). Books were published guiding parents in the ways their children should be walking, sitting and even dressing,(Kimball 1918). Growing concern that the traditional pointed shoe was causing children’s feet to become deformed was echoed in products like the “educator shoe” shown below. Products like this were advertised in children’s magazines as a way to market them to children who would in turn – hopefully – convince their parents to buy it (Jacobson 2004).

A growing economy

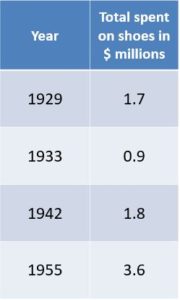

Poor children’s access to shoes changed dramatically as it became easier to mass-produce footwear (Historical Statistics), as shown in the chart below that depicts the amount of money families spent on shoes increased over time, though it did drop in the 1930s due to the Depression (Historical Statistics).

The increase in shoe consumption is also the result of a growing material culture that suggested people should have multiple articles of clothing not just for different occasions, but for everyday diversity (Cook 1995). Increases in standard of living across the country enabled people to spend more on clothing (Historical Statistics).