Common Childhood Disease

At the turn of the 20th century, there was a societal shift in how children were valued. In the context of broad economic and cultural changes, parents moved away from relying on their children for household and waged labor and encouraged their children to attend school and have playtime, which had previously been the sole realm of the middle and wealthy classes. Before this shift, rural families were often large to ensure workers for farms. In cities, children often went to work with their siblings in factories, which occasionally proved fatal for children, or participated in piecework in tenement homes (Riis, 1892). As broader society saw the impacts farm and factory work had on children, they began to rethink the meaning of childhood. Accidental death by way of factory machines, farm tools, and playing in the street were the driving forces for the cultural moral panic that led to the perception of a child’s life as priceless. Losing a child unexpectedly, and tragically, was extremely difficult for parents, “mourners’ manuals instructed parents how to cope with the tragedy of a ‘vacant cradle,’ while countless stories and poems described with great detail the ‘all-absorbing’ grief of losing one’s child,” (Zelizer, 1985 p. 26). Industrialization and the related shifts away from agrarian economies resulted in a decline of fertility and family size; as parents began to have fewer children and prioritize the ones they had by making sure they had an education, were fed well and kept healthy, as well as giving time for play. While parents tried their best to keep their children safe, they had to face another obstacle of their children possibly contracting a deadly illness. Epidemics began to plague the lives of children as “infectious diseases, including measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, whooping cough, and smallpox …[constituted] 11.5 percent of all deaths among children below age 15,” (Preston and Haines, 1991 p. 6). Diseases were easily spread by children and parents were often ill informed on how to soothe their sick children, leading to a societal demand for medical advancement on treating diseases in hopes of saving their now precious children.

As education and leisure time for children grew, so did the need for childhood spaces like schools and playgrounds. Some areas found this difficult to adapt to, as local funding was limited, which led to schools being poorly equipped to handle the spread of illness. In rural agricultural towns, many schools lacked proper toilets and instead had outhouses that were close to where schoolchildren would play, causing many to contract hookworm through the contaminated soil (Folks 1922). Schools that experienced these sanitation problems were known for spreading dangerous diseases, instilling a fear in parents that if they sent their child to school, they might catch a fatal illness. Gertrude Folks’ study on 183 rural schools in West Virginia found that “forty percent of the schools visited reported some kind of an epidemic this winter. Thirty-two schools reported measles, 15 whooping cough, 14 mumps, with a smaller number reporting other troubles such as chicken pox, itch, small-pox, scarlet fever, grippe, etc.,” (Folks, 1922 p. 107). As children more commonly caught illnesses from schools, it forced adults to rethink the role of sanitation within schools and other public spaces and prompted physicians and other medical professionals to address the spread.

Story Map

When children came home from school or being out to play and fell ill soon after, it was usually up to parents to determine what the child was sick with before it became common to bring a child to the doctor. Parents had to be able to identify the symptoms of different illnesses being spread at the time and treat them with home remedies, which were not prescribed by doctors. Because of this, families eventually became well-informed about illness from a non-medical perspective as best they could, but diseases that might be fatal needed attention from medical professionals. As visits to or from the pediatrician became more regular for children, doctors soon realized that treating children wasn’t the same as treating adults: “There was never a direct method of knowing directly what the patient perceived, and thus there was an absence of “subjective phenomena,” and this absence of direct patient history was often implicated as a significant factor in the resistance of the pre-nineteenth-century medical profession to involvement with childhood disease,” (Gillis, 2005 p. 400). Difficulty diagnosing and providing children with treatment was a challenge doctors faced as modern medicine was developing, with disagreements about true causation of disease in relation to germ theory, environmental factors, and general hygiene and sanitation (Preston and Haines, 1991). Despite these challenges, advancement in modern medicine made headway in part through the influence of society’s goal to fix the diseased child.

How Childhood Disease Influenced Modern Medicine

Timeline of (mis)Understandings of Disease

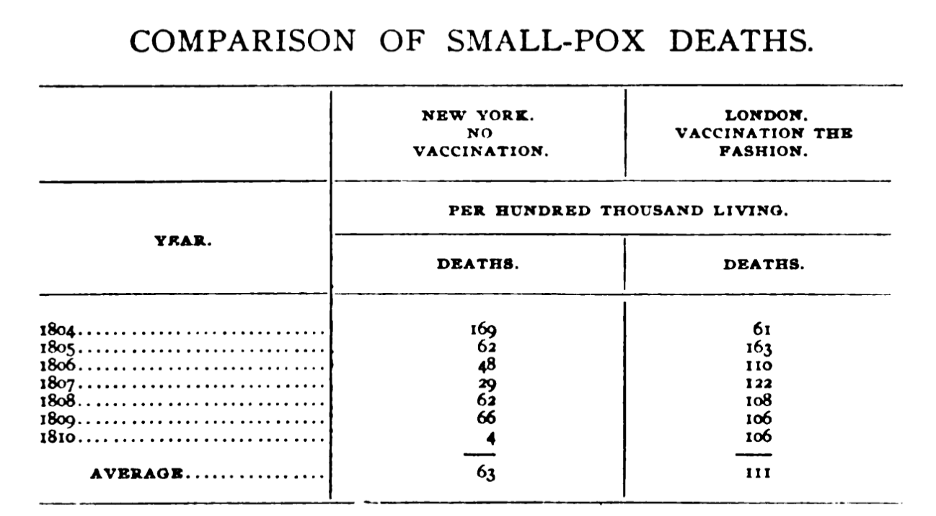

As society continually became industrialized old health practices began to merge with modern advertising and mass production, leading to many advancements in health, such as awareness of issues, government programs, and the widespread use of new products. But industrialization and the growth of society did not always lead to a progressive, or more accurate, view on medicine and child health. As one doctor who was a critic of the smallpox vaccine said in a medical journal, “Every child successfully vaccinated will carry on its body the scar — the brute-caused scar, the grievous sore, the scar of the “beast” — till death” (Peebles, 1905, p. 55; see table).

Nonetheless, clear advancements were made. Germ theory was developed in 1861 by Louis Pasteur by showing that the growth of microorganisms in a broth could be prevented by avoiding atmospheric contamination (Preston and Haines 1991 p. 7). This revolutionized modern medicine and the general understanding of illness prevention, though its progress and adoption was slow and uneven across regions.

Improvements in care

By the late 19th/early 20th century many institutions and laws had been passed to standardize practices of childcare and childhood health in response to the most common “childhood diseases”. In 1889 the first meeting of the American Pediatric Society was held, and in 1906 The Pure Food and Drug Act passed due to widespread propagation of media around issues of health. In 1910 another organization called The Little Mother’s League of New York City was formed to combat infant mortality by training immigrant girls to care for their baby siblings (Olson, 2017). The formation of these laws and institutions shows a strong pivot towards prioritizing child health, however, it is important to note that at the same time things such as heroin and cocaine were still being marketed to children as remedies for common illnesses (National Library of Medicine). This shows a tension in society; the institutionalization of childhood health was well on its way, but archaic and underinformed practices still dominated much of what was administered in the household.

Demographic Data:

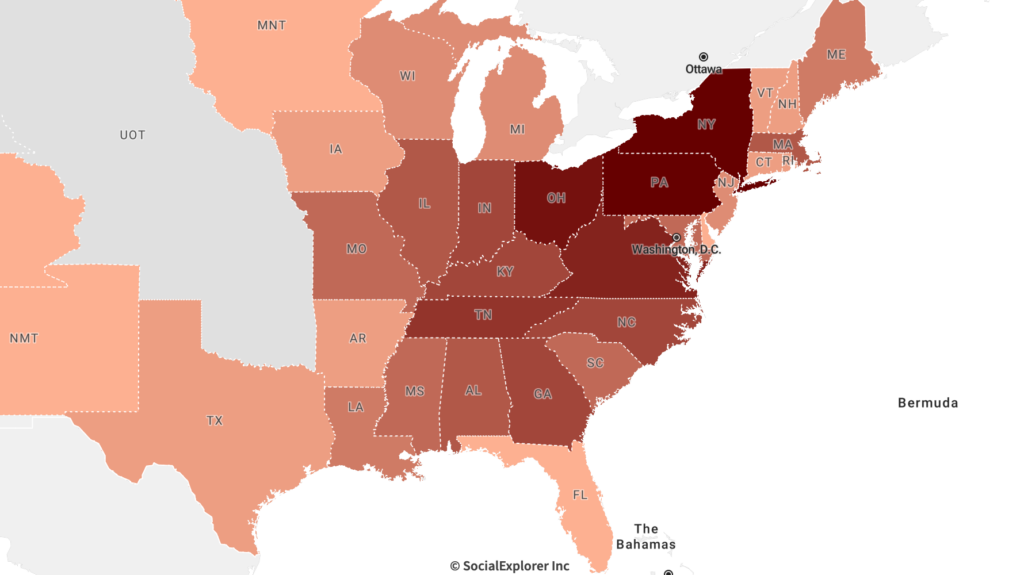

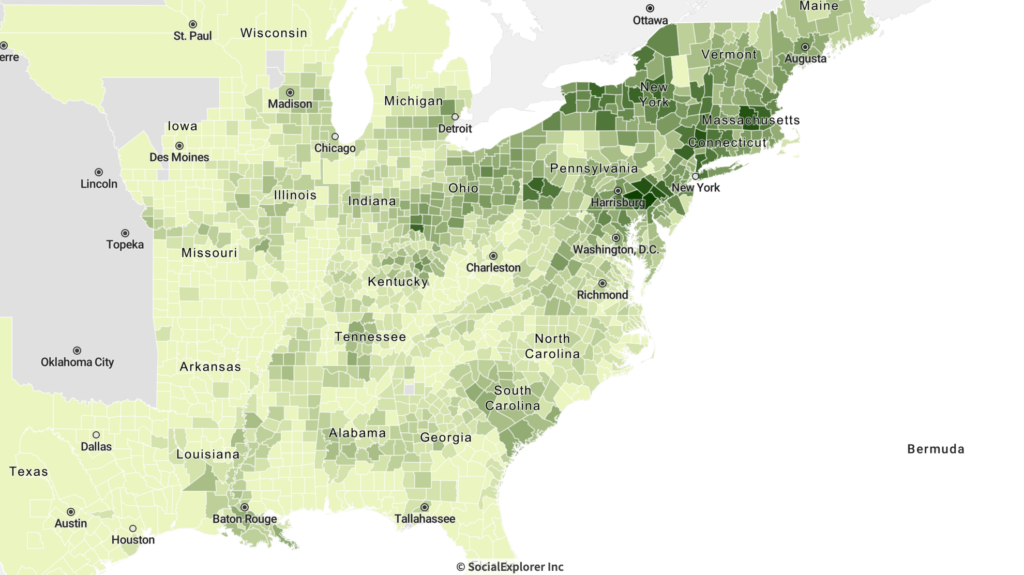

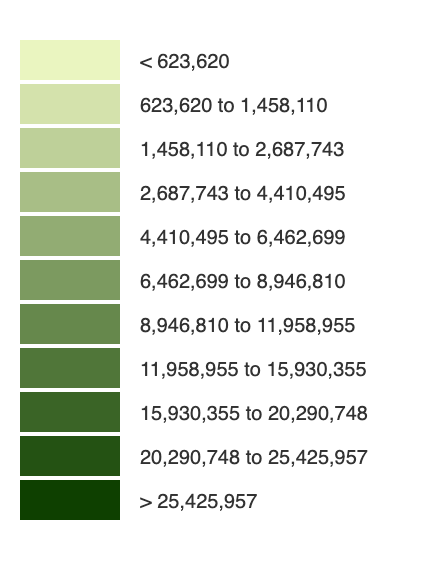

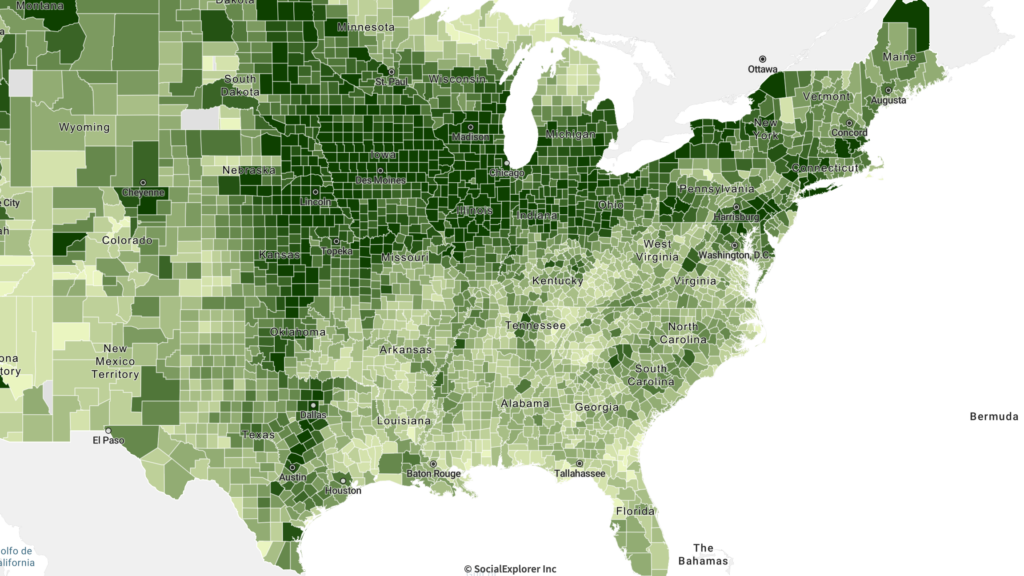

Using the tool Social Explorer, US Census data allows us to find common trends and patterns in the communities that can help deduce whether populations and certain demographics of people/children have been affected by diseases. We looked at two specific trends; Population by Ages of Youth and Value of Farms from 1850’s to Early 1900’s (NE).

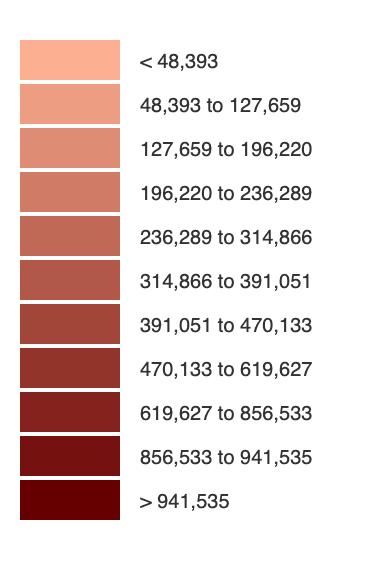

less) in 1850’s by State

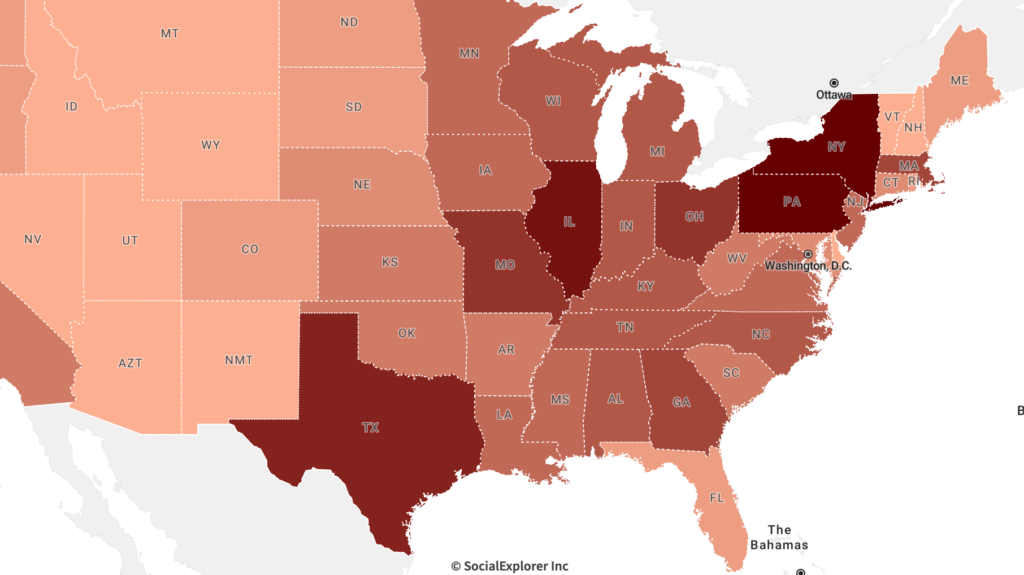

less) 1910’s by State

Some of our tentative observations from these data include:

- The growth of youth populations in the South and Midwest.

- More jobs open means more labor and families, with children who need to either work or go to school.

- Higher population density also leads to higher exposure of diseases and illnesses and high mortality rates, but also spurs innovation in medical advancements and technologies.

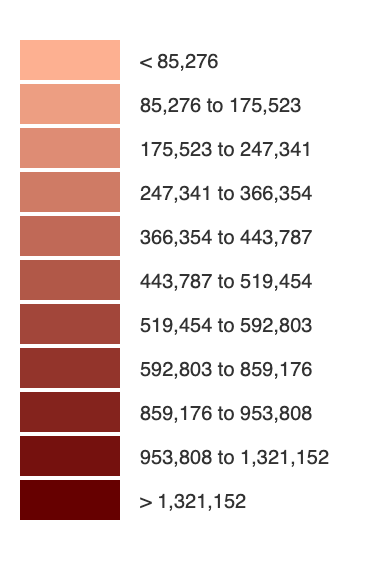

1910’s by County

Some of our tentative observations from these data include:

- We choose to look at the value of farms due to the connection to milk/dairy production since a lot of health issues for children in this time period surrounded health laws and social questions surrounding pasteurized milk processes.

- Malnutrition was also a leading cause/cycle tied to diseases such as Cholera

- Quality of water, land and produce (food).

- Also the expansion of land and poverty trends in rural/urban areas.

- From 1850-1910, the economic value of farms shifted towards the midwest/southwest.

- Urban areas had higher death rates due to diseases than Rural areas.

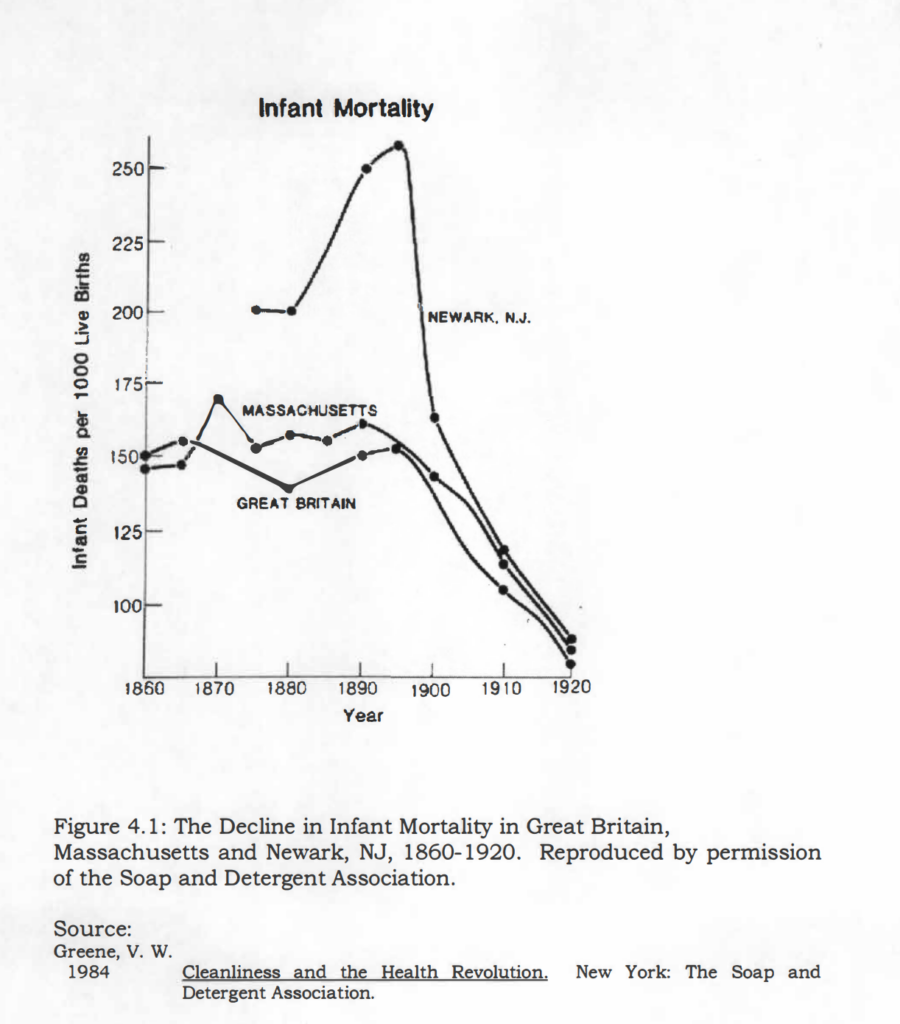

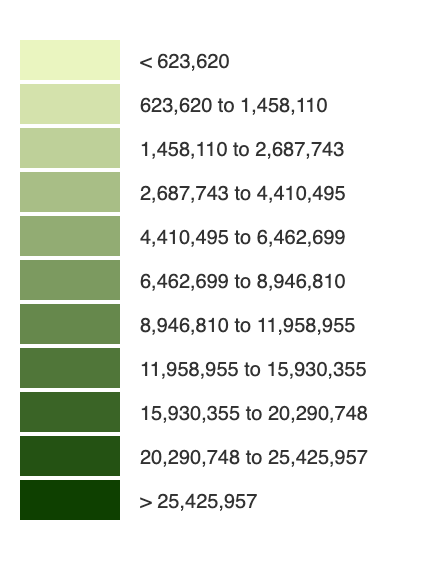

Figures 5 & 6. Major Epidemics Death per 1000 population & Infant Mortality rate

- By looking at the major epidemics thought the 1850-1920 time period and comparing it to the infant mortality rate thought these, centuries you can tell smallpox was one of the highest causing diseases related to death rate of infants in the 1890’s in the New Jersey area.

- Also a few large epidemic of Cholera in early 1800’s, higher in west and south than in NE areas.