The scholarly work we have reviewed demonstrates the relationship between the reactions of adults to a children’s epidemic and what these reactions indicated about societal attitudes toward children. Reactions to the 1916 polio epidemic prove the fundamental shift in American perceptions: children became valued as “precious” and worthy of protection.

Empirical evidence directly related to the polio epidemic that appears in the literature include efforts to contain polio through the “sacralization” of children, quarantines and hospitalization, the public’s ability to set aside their fear of immigrants, parent reactions and the use of “poster children” to advocate for vaccines. These all emphasize the construction of childhood, children’s varied experiences, and the conceptual themes of how society views children as “precious” and emphasizes their protection.

1. The “Sacralization” of Children

The perception of children in America as sacred directly led to the search for a polio vaccine. In the first chapter of Viviana Zelizer’s piece, “From Mobs to Memorials: The Sacralization of Child Life”, the author specifically focuses on providing evidence for this claim. As we discussed this semester, this is the author who notoriously said children became “economically worthless but emotionally priceless” at the turn of the 20th century. The first chapter, Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children, is useful to our overarching analysis because it emphasizes the point that there was a change in national attitudes towards children that directly corresponded to the way healthcare was dealt with in America.

For example, the author discusses how the “sacralization” of children in the 20th c. led to an increased intolerance of child death, whether by illness or accident, and a great concern was protecting child life. Children of all social classes were not only vaccinated against disease and better nourished, but their lives were increasingly supervised and domesticated (Zelizer, 1985).

Additionally, to further prove the early twentieth century was characterized by a surge of public concern with child life and a new recognition of the sentimental worth of children, we can look to the public funding such as The Sheppard Towner Act of 1921 provided federal funds to protect the health of infants and mothers (including from polio) and the establishment of the US Children’s Bureau in 1912 which was extremely useful for tracking data on child mortality and illnesses including polio.

2. Efforts to Contain Polio through Quarantine and Hospitalization

In Passage Through Crisis; Polio Victims and Their Families “Ch 3. Perspectives on Recovery: The Child in the Hospital” and “Ch 4. Perspectives on Recovery: The Child at Home” Davis (1925) discusses the experiences and practices that went into caring for a child with polio outside of the home when they are either quarantined or in another hospital setting. These chapters consider the recovery period during hospitalization, the impacts and effects of the child’s removal from the home, and the alterations to the child’s experiences and health outcomes after the child returns home. For example, one passage states “the transfer of the child from the receiving hospital to the convalescent hospital plays an important part in the socialization process. While in the receiving hospital the child is in pain much of the time and, because of the danger of contagion, is kept in isolation.” However, when the child is transferred out of the quarantine environment the author notes that “life seems much less deprived. He is placed in an open ward with children his own age with whom he can talk and play. Games, movies and television are provided. A schoolteacher, an occupational therapist, and various volunteer workers visit his bedside. On visiting days his parents can come directly up to him and do not have to talk at a distance. These pleasures of sociability after the days of isolation have a telling effect on the child and contribute much to their positive involvement in the treatment regime” (Davis, 1925, p.69).

Essentially, the reflection on what a child is experiencing in terms of their mental wellbeing due to social isolation from polio hospitalization reflects a new level of appreciation for the child. Not only did parents and doctors look to hospitalize their sick children to protect them, they desperately attempted to avoid isolating children from others because they wanted to protect the child’s precious mental well being as well. Additionally, the coddling of sick children in the hospital with entertainment and education is a new theme that shows how individual children were now seen as “precious”.

3. Setting Aside Immigrant Fears

Views towards immigrants in the early part of the 20th century were not positive and many American citizens thought they were responsible for disease. However, these views were capable of being put aside if it meant protecting children from Polio in the context of emerging cultural values that considered children “precious” .

In Chapter 5 of Oshinsky’s book, Polio: An American Story the author focuses on the 1916 polio outbreak in New York City. According to him, “almost everyone assumed that poor living conditions– filth, poverty, overcrowding, and ignorance– were responsible for breeding epidemic disease” and “most people believed that polio had been brought into the better neighborhoods by immigrant carriers who worked as cooks, maids and chauffeurs; by disease-bearing insects that had traveled up from the slums…” (Oshinsky, 2006, p.22). Yet polio did not appear to fit this mold. In NYC, for example, “health officials found the epidemic to be most prevalent on Staten Island, which had the lowest population density and the best sanitation conditions of the city’s five boroughs” (Oshinsky, 2006, p.22).

The implication of these facts was that the 1916 epidemic suggested a different reality, at odds with the general consensus of the time. The public wondered “if it was possible that those who lived in crowded, unsanitary conditions had been naturally immunized by exposure to poliovirus at an early age?” The underlying question public health officials, researchers and the general public were trying to get at was if it was possible that living in dirty environments associated with immigrants actually protected children from the disease (Oshinsky, 2006, p.23). While these facts provide evidence for broader trends in how American culture viewed immigrants at the time, it also suggests that these harsh views could be set aside if it meant progress could be made on understanding a disease that afflicted the ever so “precious” children of the era.

4. Reactions of Mothers and Parents

We can look at the way mothers and parents reacted to Polio outbreaks at the beginning of the 20th century to see how their attempts to protect their children from harm reflected changing attitudes. For example, Chapter 5 of Oshinsky’s book, Polio: An American Story includes accounts from mothers about their experiences rallying around prevention and care for children with Polio. The author claims “it was hardly surprising that the National Foundation focused on housewives and wage-earning mothers as the ideal foot soldiers of the polio crusade — women with a few hours to give and a good reason to get involved” (Oshinsky, 2006, p.86). This quote demonstrates why mothers got involved in fundraising for polio – having children had become a decision, a “self-conscious act”. When Polio came about it was a crack in the fantasy of the ideal family. How mothers and parents got involved was through specific philanthropy initiatives. Though the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis came later than our time period-in 1938 during the FDR presidency- it still points to a growing consensus that had been building for the past few decades. When mothers joined these volunteer campaigns dedicated to protecting their loved ones from the ravages of child-based epidemic disease as opposed to other philanthropies, “they were more likely to view their task as a parental obligation” (Oshinsky, 2006, p.86). Fundamentally, this piece is illustrating how protecting children from polio became not only charity work, but an obligation for parents, particularly mothers.

Furthermore, according to Preston and Haines in their piece on the Fatal years: Child mortality in late Nineteenth-Century, parents at the time “seemed in general to be highly motivated to improve their children’s health, but they had relatively few means at their disposal to do so” (Preston & Haines, 1991). Overall, when we look at the ways parents reacted to polio in terms of fundraising attempts and overall attitudes of deep care for their children, we can see how much they cared about protecting child welfare.

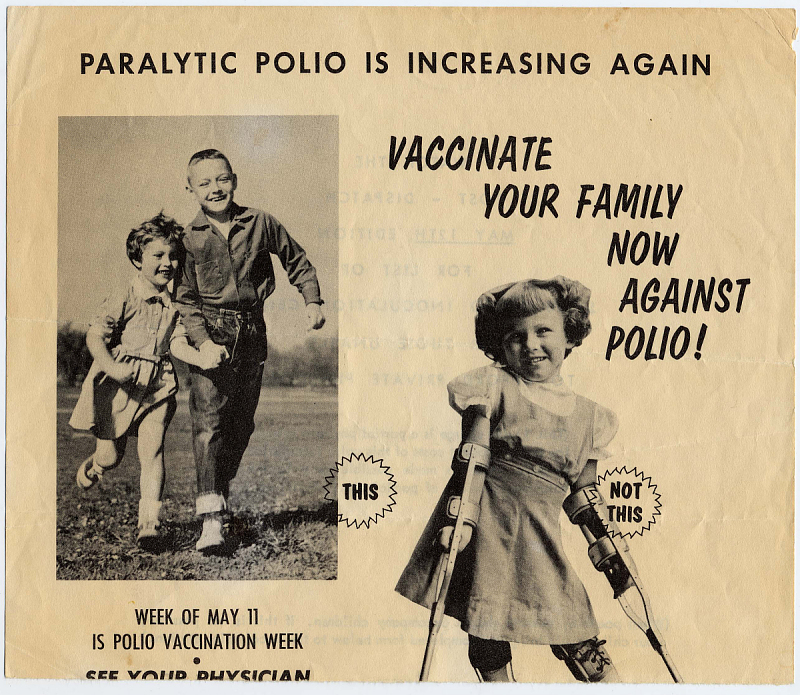

https://www.si.edu/object/polio-vaccination-poster%3Anmah_1282853

5. Using “Poster Children” to Garner Support For the Polio Vaccine

As the picture above illustrates, children were often used in advertisements to promote the vaccination of more individuals and proper sanitation practices. The literature suggests that during the period closer to our target era of 1900-1930, when polio was still running rampant through society, children were also used as “poster children” to promote cleanliness practices and vaccinations. The National Foundation of Infantile Paralysis, for example, ran these ads to appeal to attitudes to protect the nation’s “precious” children. They knew that by claiming the protection of children would be a result of polio vaccine research and formulation, they could encourage government and philanthropic funding for the cause.

In “Chapter 5: Poster Children, Marching Mothers” of the book Polio: an American story, Oshinsky specifically focuses on how changing views about children being seen as increasingly in need of protection and saving led to such advertisements to raise funds. One such example is advertisements of a child named “Donald” who was shown before and after recovering from polio. Oshinsky states that “For the National Foundation, Donald Anderson. Perilously close to death, had been saved and brought back to health by the contributions of ordinary Americans to the March of Dimes” (Oshinsky, 2006, p.83). Millions could see the “fruits of their generosity” through the progress of this “precious” boy. While this ad was run towards the end of the period of focus, it still plays on the now widely accepted societal norm that had been built up starting at the turn of the 20th century that a child’s life was, in fact, precious.