Timeline: A Brief History of Polio in the Early Twentieth Century

This timeline stretches from 1894 to 1939 identifying early outbreaks of polio, scientific developments, and key historical events. Although we will be focusing primarily on the outbreak in New York City in 1916 and the cultural/social implications on the lives of children, it is important to provide a timeline that showcases the historical events on each side of that case study as well as to give context. Polio, also known as infantile paralysis, was predominant throughout the twentieth century. Polio is a virus that spreads through contaminated food or water, specifically fecal-oral transmission (New York State Department of Health 2014). The scientific development of treatments like the Iron Lung and later the vaccine had tremendous impacts on the lives of children and their ability to survive this disease. Franklin D. Roosevelt became a figurehead of polio after he contracted it in 1921. He also founded The National Foundation of Infantile Paralysis, later renamed the March of Dimes Foundation. This foundation raised money for polio research and helped patients and their families in recovery, playing a significant role in the childhoods of children with polio.

Childhood Inequalities of Polio

One of the themes revealed by our research into the polio epidemic was that of inequality. Much like with the epidemic of car crashes that occurred earlier in the century (Zelizer, 1985), the lives of children from certain groups were given much more worth than others. Inequality was present in all aspects of the social response to the disease, from access to treatment, to the crafting of public health policy. Even whether one was acknowledged as a victim of the disease depended greatly on one’s social position.

The Street: Sanitation and Anti-Immigrant Bias

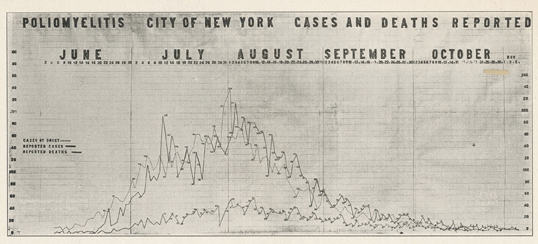

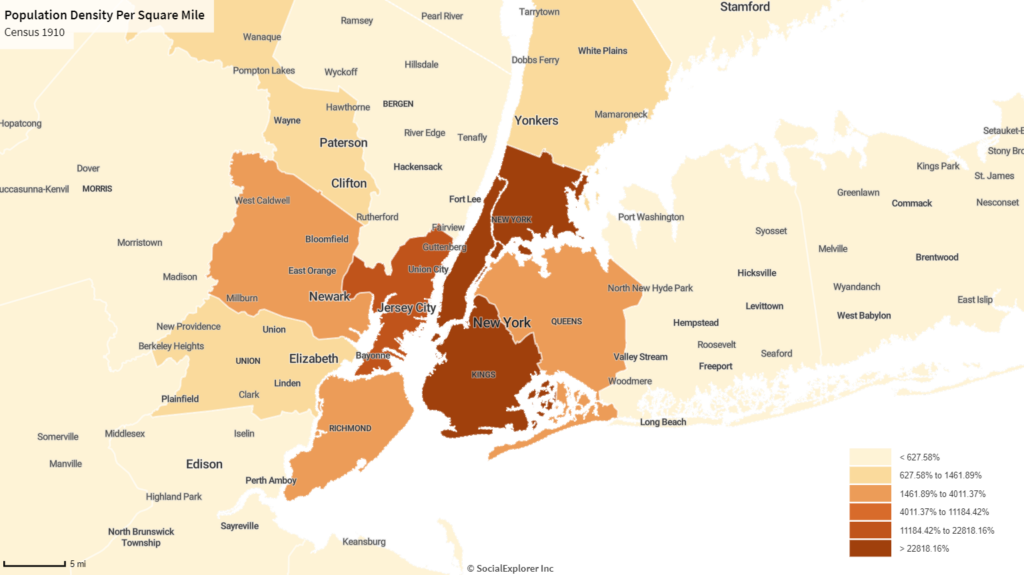

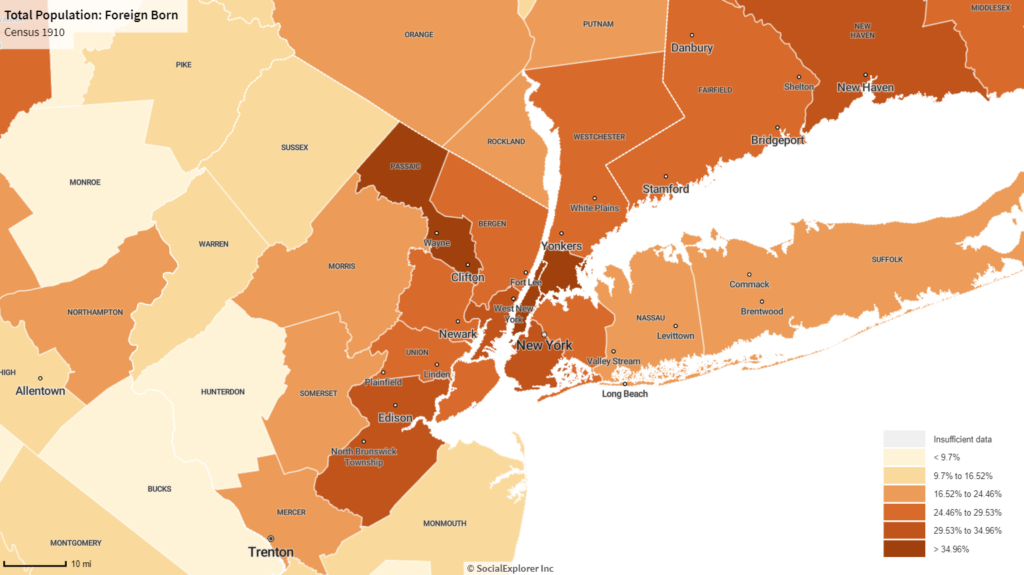

Public health measures during the 1916 pandemic overwhelmingly targeted immigrant communities. Oficials primarily focused their efforts on the densest boroughs and those with and highest percentage of immigrants, falsely assuming both these variables contributed to the spread of the disease (Rogers, 1989). As such, public health officials also responded with these vectors in mind: clearing the streets of trash and culling the streets of stray animals along with ordering mandatory quarantines (Offit, 2005). Tragically, it was actually the areas with lower density and lower immigrant populations that suffered most during the outbreaks with areas like Richmond Country and Queens County (highlighted in orange above) suffering the most during the outbreak (Rogers, 1989). However, due to the fact they did not fit preconceived ideal of a contagious area, these boroughs received little public health assistance during the epidemic (Rogers, 1989).

The Household: Quarantines and Tenement Families

In 1916, health officials declared that all exposed to polio would need to quarantine in an effort to reduce infection. Although seemingly a noble goal, the strict regulations that accompanied the quarantine overwhelmingly harmed immigrant populations, particularly those dwelling in tenements-style housing (Offit, 2005). Those who resided in tenements rarely had access to items required for children to be quarantined at home (e.g., private bathrooms and bedrooms,) and therefore exposed children were instead taken to hospitals (Offit, 2005). However, due to the popular impression (unfortunately accurate) of hospitals as spaces that killed more than they saved, parents heavily resisted any attempts to take children out of the home. Police were often brought to enforce orders and many immigrant groups soon began to cease cooperation with public health officials (Preston & Haines, 1991) (Offit, 2005).

Tenement Families frequently lacked private toilets’ and other spaces animalities considered essential for children to be properly quarantined from the rest of the family

The Treatment Center: Polio and Medical Segregation

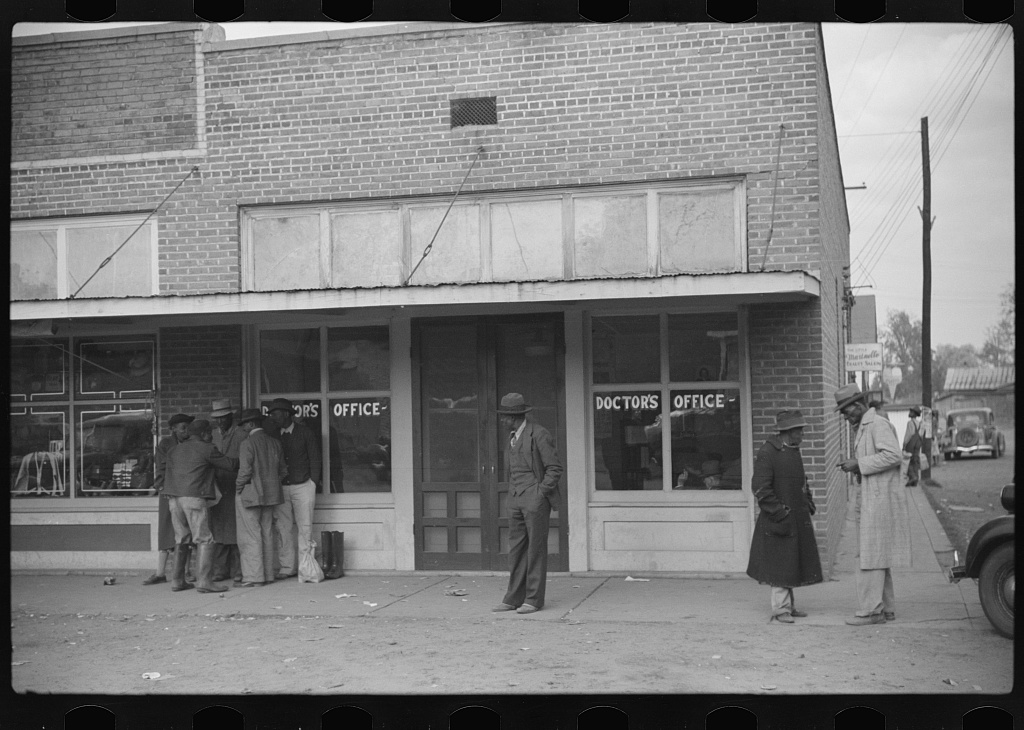

By the 1920s, polio was acknowledged to be a disease not specifically caused by the urban poor (though its higher prevalence among the wealthy went largely unacknowledged) (Rogers, 1989). However, bias persisted into the 1920’s in how the disease was viewed by both government agencies and the public. Instead of blaming specific groups for the spread of disease, this new form of bigotry would ignore the suffering of certain groups entirely. African-Americans—and African-American children in particular–received little attention from public health officials as their low recorded rates of infection during urban outbreaks led many to assume they had a “natural immunity” to the disease (Rogers, 2007). However, these statistics were often viewed without proper social context. African-Americans generally lacked access to healthcare, many polio victims went undiagnosed and untreated, and countless cases of polio undoubtedly went unreported. Despite criticism from Black Physicians, public officials continued to assume into the 1940s that there were few to no Black polio victims and in the context of a period of medical segregation, this led to little to no paralysis treatment being available to Black victims as nearly all treatment centers were for whites only (Chenault, 1941) (Rogers, 2007).

For more information on the inequalities of Polio click on the StoryMap at the bottom of the page.

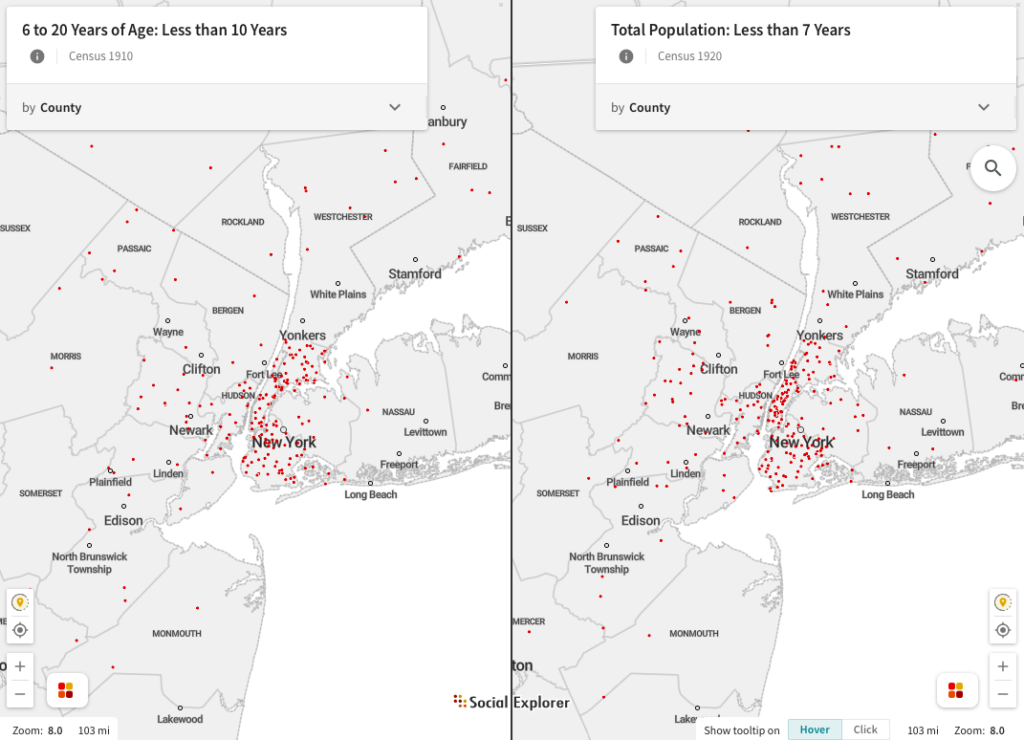

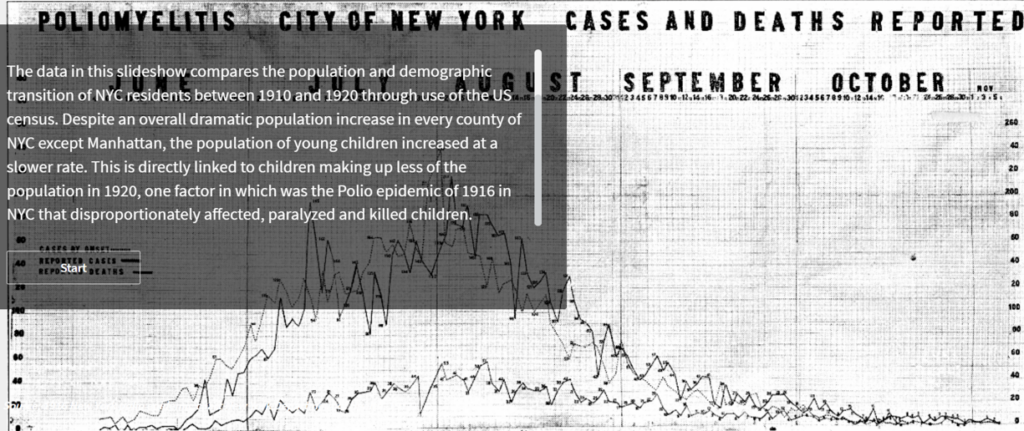

Census Data — Demographic Transition Trends: NYC Polio Epidemic of 1916

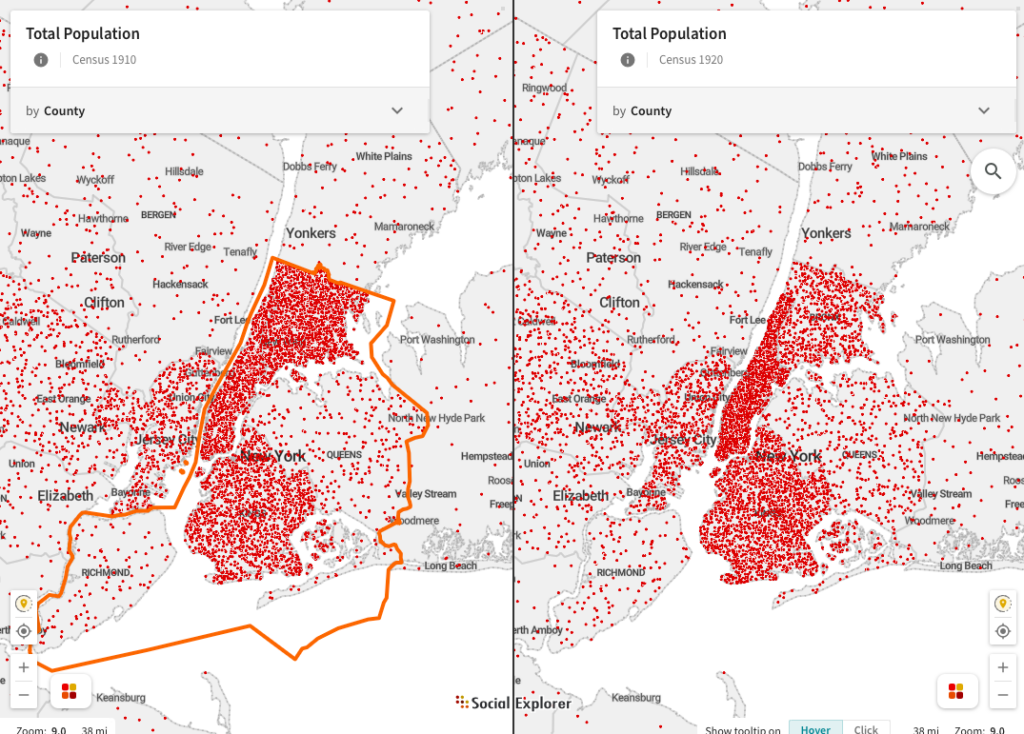

The data in this Social Explorer slideshow compares the population and demographic transition of NYC residents between 1910 and 1920* through use of the US census. Despite an overall dramatic population increase in every county of NYC except Manhattan, the population of young children increased at a slower rate. This is directly linked to children making up less of the population in 1920, one factor in which was the polio epidemic of 1916 in NYC that disproportionately affected, paralyzed, and killed children.

The first data comparison shows the increase in young children between 1910 and 1920. Using Kings county, also known as Brooklyn, as an example we can see the number went from 128,883 children under 10 (7.9% of the population at the time) to 296,658 children under 7 (14.6% of the population at the time). This is a percent change of 6.7%.

The total population of Brooklyn, however, increased from 1,634,351 people to 2,018,356 in the same period– an increase of 23.5%. Usually when populations increase during a time period the percentage of children increases at the same or higher rate. This is an unusual example where very high infant mortality rates, high levels of immigration by mostly single adults and infantile paralysis and death due to the Polio epidemic lead to a slower increase in the percentage of children in the population.

This difference indicates the impact of many trends during the early 20th century, one of which was the Polio epidemic of 1916 had on NYC population demographics.

*It should be noted that the census data collected during 1920 could only be found for children less than 7 years old, which is being compared to children less than 10 years old in 1910. While this discrepancy potentially undermines our point, we think the difference between the two groups is significant enough to outweigh this.

New York City Paralyzed – A Case Study StoryMap of the 1916 Poliomyelitis Outbreak

The 1916 polio epidemic that plagued New York, from the boroughs to rural upstate communities, exposed the vulnerability of children to disease and the tactics taken by adults to counter the physical and social threats of this illness. The StoryMap (below) chronicles the first steps of the geographic spread of disease from New York City up to Beacon, NY. The social implications of how different communities in the boroughs of the city responded to and were affected by polio are discussed by demographics including but not limited to, immigrant status, age, socioeconomic status, and race. Staten Island served as a unique and quite literal “island” in this case study, showing how immigrant status, volume of children under a certain age, and public infrastructure forced this community to experience different social determinants of health than families of different backgrounds. The analysis in the StoryMap also brings the experiences held by mothers and children of a certain ages that were exposed to or suffered from polio. Drawing comparisons to the COVID-19 pandemic of this decade, we are able to see and take lessons from early pandemics and think critically about the ways that we have experienced the spread of disease, how it has impacted our children, and the way families respond to the vulnerability of their kids.

Final Discussion

The social responses to the polio epidemic clearly demonstrate the power the idea of the new precious child had on public policy. Isolation wards and care facilities with designed with an emphasis on meeting both children’s medical and emotional needs (Oshinsky, 2006). Prejudices could be set aside (to a point) to enact policy with the aim of protecting all children, not just the privileged. Parents were devastated by polio because of its disruption of the sheltered childhood and vigorously campaigned for further research (Oshinsky, 2006). Children’s preciousness was even used strategically in form of advertisements urging the public to donate to fund research and treatments (Oshinsky, 2006).

Despite our examination of the responses to the United States polio epidemic demonstrating (more broadly) the new social value children held during the 1900s, they also reveal that this value was by no means given to all children equally. Police dragged immigrant children from their homes in the name of public safety and health (Offit, 2005). Most rural families had no accessible treatment options nearby, and most rural children were forced to make do with home remedies and improvised assistive devices (Wilson, 1989). Black children who suffered from the chronic effects of the disease were often ignored completely, with medical segregation resulting in almost no treatment being available to them (Rogers, 1989). All children may have been given more value during the 20th century, but it is clear that governments and public health officials valued the lives of some children more than others.