Fear as Discipline

The overarching theme in analyzing historical accounts of children’s fears is that fear is a phenomenon based on social and cultural implications, and the cultural shifts in fears in terms of childhood illustrates how the definition of the ‘child’ has changed over time. In a multitude of ways, the fear that children experienced was brought upon by a force outside of themselves. Rather than simply focusing on fears that children experience such as monsters, scary stories, and embarrassment, a broader application of historical and scholarly sources works can be examined and utilized easily to highlight how societal beliefs and values at the time manifested into how children experienced fear.

It is evident that fear was used as a disciplinary tool, both by parents and the nation in general. Historical accounts stated that driving fear into children can result in creating a “moral” child, sometimes by using physical punishment towards “bad children”: “…if administered as a last resort, and made the basis of an appeal to the child’s imagination in the future, it may arouse a fear that will be the beginning both of moral wisdom and of self-control” (Tanner, 1915, p. 307). Discipline and punishment drove fear into children to act a particular way, based on the ideal form of a child, which was obedient and innocent as compared to the adult.

Others took a different approach. A 1922 account of addresses before the Ethical Culture Society of New York City claims that corporal punishment can break the child’s spirit and counteracts the concept of “moral reformation” of the child, as harshness can reduce the child’s ethical sensibilities (Adler, 1922, p. 17). While there may be different perspectives on the “correct” forms of discipline and punishment, the notion of disciplining the child into an ethical and moral being was a common point of discussion in cultural discourse of the time. Learning a lesson from the parent instilled fear so as to not break the cultural “norm” of child behavior.

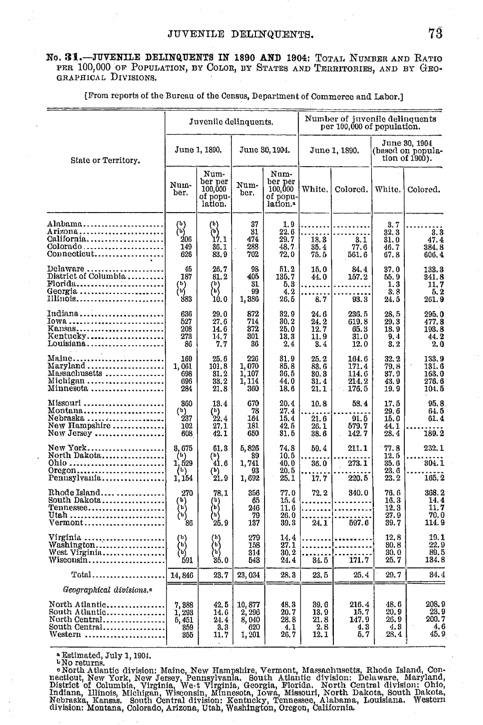

Continuing with discipline and punishment, the beginning of the 20th century introduced records of juvenile delinquency, keeping record of children who were considered deviant or criminal by state and race:

The United States was now tracking children’s behaviors with a more focused, concise lens, separating the child from the adult in terms of criminality and punishment. We can also see how the data in the table is being compared between 1890 and 1904. Recording juvenile delinquency exemplifies a trend in adopting more structured forms of discipline towards children, which as this analysis will work to show, was used to instill fear into children.

The apparent shift towards more structured forms of discipline can also be linked to the shift away from the laboring child to the domestic child in the early 20th century, where the behaviors, expectations, and goals of children were constricted to the aforementioned “ideal”.

This storymap based on archival research highlights fears and insecurities children faced when engaging in child labor, and how these experiences thus informed the apparent meaning of “childhood” at the time:

Tying in with labor as a cultural context, war as a cultural impact influenced children’s fears, as records from the 1940s show children being scared and traumatized by the realities of war and violence. Interestingly enough, this led to a continuation of the demise of authoritarian parenting, where children experienced less negative effects after such exposure if the parent was caring and offered a sense of protection (Osofsky, 1999). The cultural context of this time period, this case involving war, highlighted children’s fears of the social world and further shifted how children were viewed by society – as beings who needed to be protected.

The emerging ideal was based on the child developing into a future hardworking adult, supporting the United States in the name of nationalism. The increase of nationalistic ideologies in the United States were driven by combinations of industrialization, restrictions on immigration, and events such as WWI and WWII, therefore forming the extension towards disciplining well-behaved children on top of “bad children”. This discipline was based less on parental discipline and more on restrictions and controls of the child at the societal level.

Fear, Discipline, & Nationalism

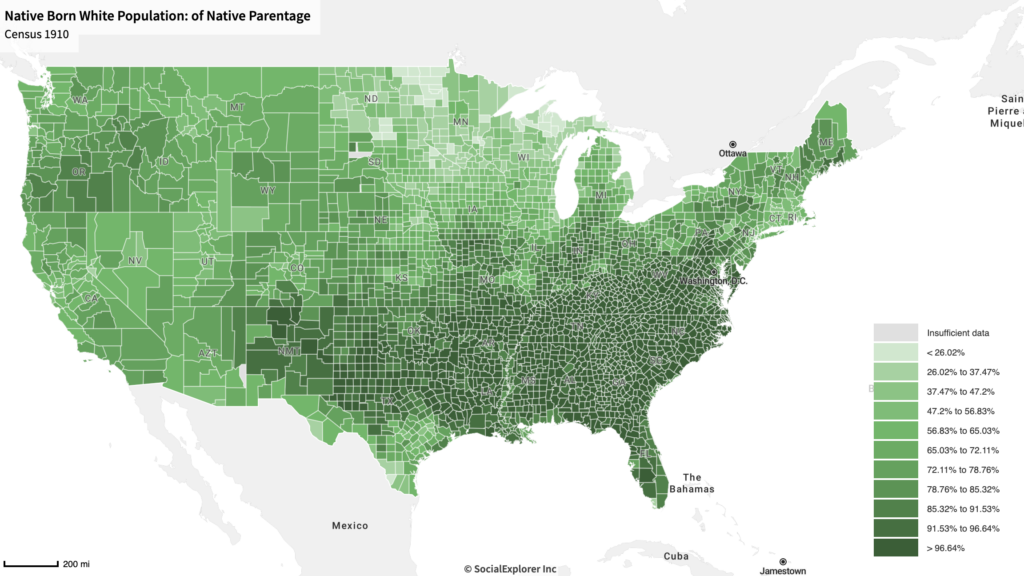

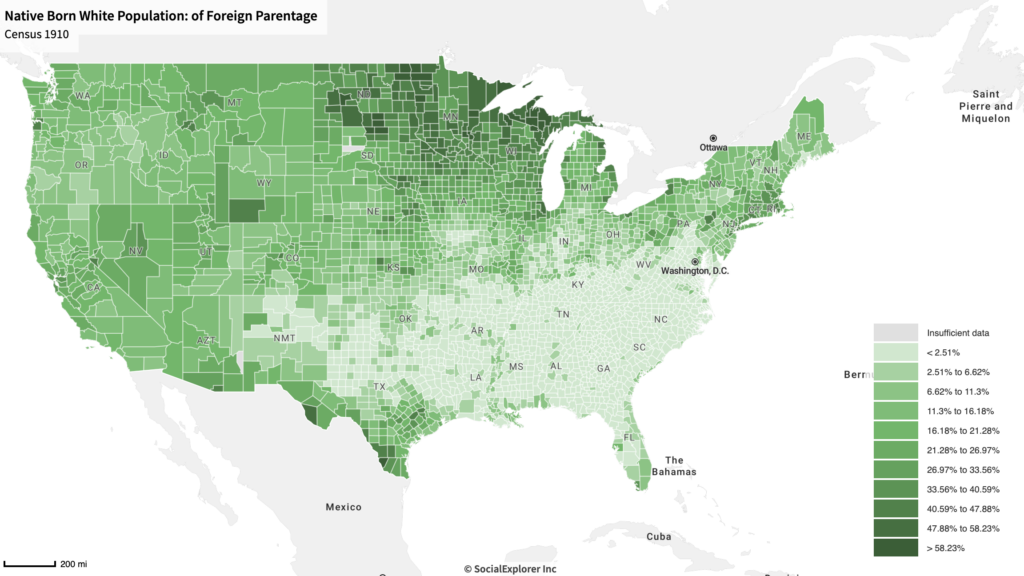

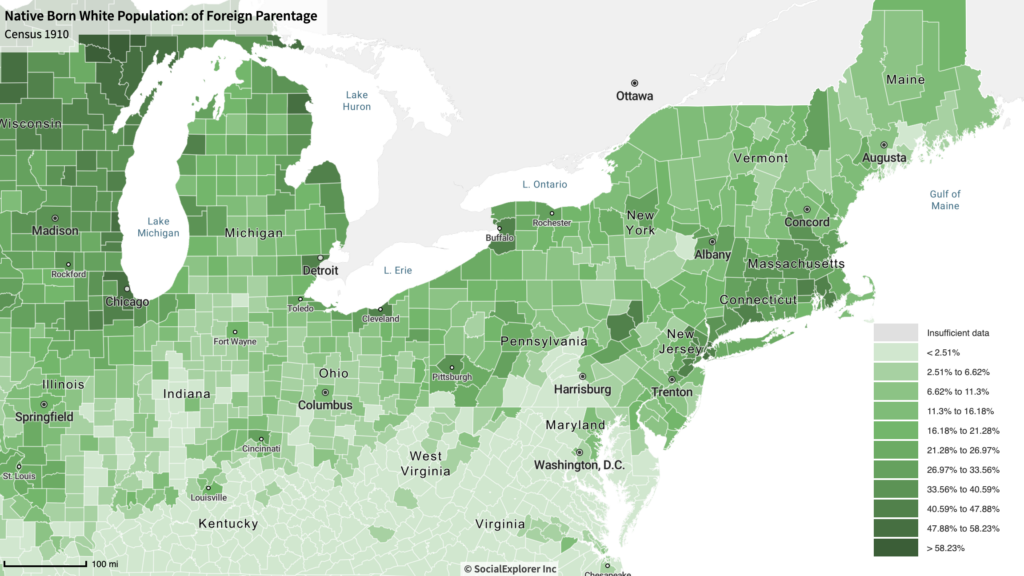

As demonstrated in the following maps, higher populations of native white parentage fall within the Southern portion of the United States, while the majority of higher populations of foreign white parentage fall within the norther portion, sometimes even the West.

Looking closer, higher percentages of foreign white parentage can be seen in areas in or around New York City, Boston, & Chicago.

Evidently, most of the areas high in percentage of native parentage correspond with more rural settings, and vice versa. This aligns with the cultural contexts of the early 1900s in which many people who were immigrants, or whose parents were not native to the United States, settled in urban areas, mostly in the Northern industrial zone. In turn, many of those Northern cities worked to “Americanize” immigrant children – a lot of the time, this manifested as controlling and restricting the child’s body, both physically and spatially, so as to discipline them into the “ideal American child”.

For example, as Gagen (2004) mentions, physical education was used as a tool to mold child bodies – bodies that were to become physically fit, all with a social goal to create “healthy future citizens” (p. 417), restricted at the spatial level and driven into submission, as “they injected a degree of pomp and patriotism to what was already a self-consciously Americanizing project”, considerably placing “bodies on parade” with public displays of patriotism (Gagen, 2004, p. 434).

The fear of being ostracized, punished, or left behind forced immigrant children, along with some native children in the same settings, to follow the American ideal of the obedient, patriotic child.

While there was progress to domesticate the child, remove them from child labor, and adopt child welfare reform, there is a hidden layer to these developments: discipline as a tool for instilling fear and submission into children was more subliminal than overt corporal punishment by the parent.

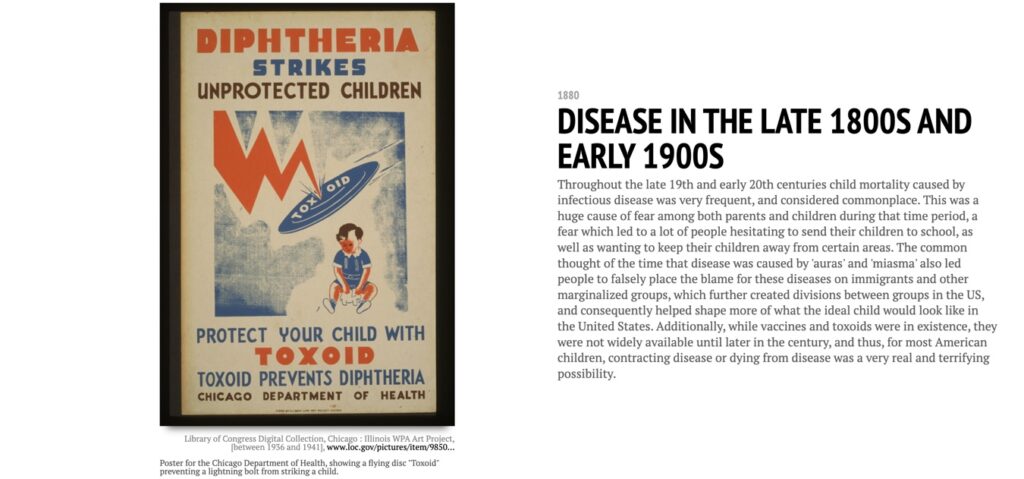

Fear and Illness

Illness and mortality as it was in the late 19th century and early 20th century was a great source of fear for children and parents alike. Life was “chancy” for children, mainly due to lack of information about disease, access, and proper care. Diphtheria, for instance, was considered “terrifying”. The health of infants and children was a concern for all, and was becoming a crisis (West, 1996, pp. 54-64).

This crisis brought on prominent feelings of fear not just from children, but from parents to children. Parents were genuinely scared of their children dying from disease, because it was so common. As West (1996) writes, “According to one authority, in 1900 about one out of every four babies died before he or she reached the age of five. That estimate may well be high, but another study concluded that in 1915 the rate of death among children during their first five years was at least 10 percent” (p. 54).

Sickness and Schooling

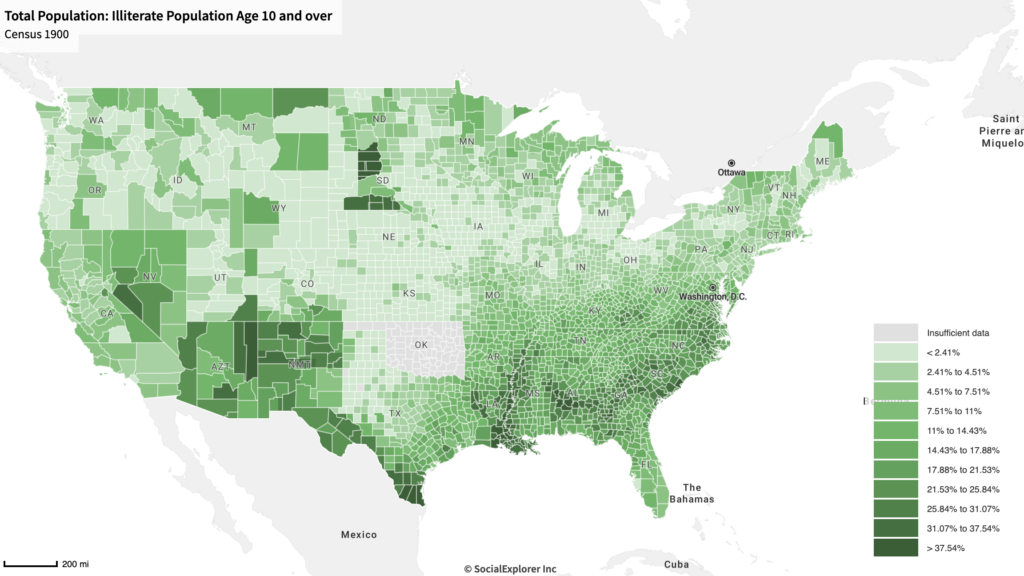

The below map shows higher illiterate populations (10 years old and older) in southern areas of the United States.

Based on historical accounts of children’s education, there have been cases of children who attended school less frequently, or did not go to school at all, out of parents’ fears of children getting sick from classmates (Folks, 1922). While there were other reasons that children had low school attendance, such as unsafe travel to school, or in other situations because children simply did not want to go, these are not necessarily based in fear.

In using fear as a lens of analysis, illness and mortality was a driving factor of low school attendance in particular areas (especially the South), going so far as parents keeping their children home because of the risk of communicable disease (Folks, 1922, pp. 104-108). Low school attendance and lack of education results in higher rates of illiterate populations. Regarding parents wanting to protect their children, “…the almost superstitious fear of illness which also keeps children out of school is totally unnecessary” (Folks, 1922, p. 107). Folks’s use of the word “unnecessary” speaks to debates of the time period geared towards improving public health and sanitation, which would work to reduce illnesses spreading as easily. In turn, this points to the social aspect of the fear of illness, as it was based on issues such as a lack of public health initiatives, poor access to medical care, and misunderstanding of disease transmission. While this fear was not strictly felt by children, fear of illness and infant/child mortality shaped children’s experiences, down to struggling with a lack of education.

It should be noted that the South, where there are higher percentages of illiteracy in the map above, also contained more agricultural space. Children in agricultural or rural settings lived farther away from healthcare institutions, leading to a deeper fear of illness and mortality as medical care was inaccessible. Geographical space was a large determinant of how fears and children’s experiences with it became a social force.

The following timeline demonstrates how social topics like disease and child labor existed at particular points in time, while highlighting the change over time towards viewing children as “emotionally priceless” (Zelizer, 1985, pp. 23-55) and shifts in disciplinary measures. All of these aspects are based in cultural events and discourses of the time, and in turn all shape both how children experience fear and how it manifests:

Overall…

It should be noted that while there are noticeable trends over time and evident social change, there are limitations to the data present. Social changes do not happen over night – they are longer, more gradual processes that can be difficult to fully examine. With these newfound changes in both the definition of the “child” and childhood, there are ideas that overlap with each other, with different people having different perspectives. Social changes and ideologies are not linear and, therefore not necessarily expected to be, in researching historical timelines of change.