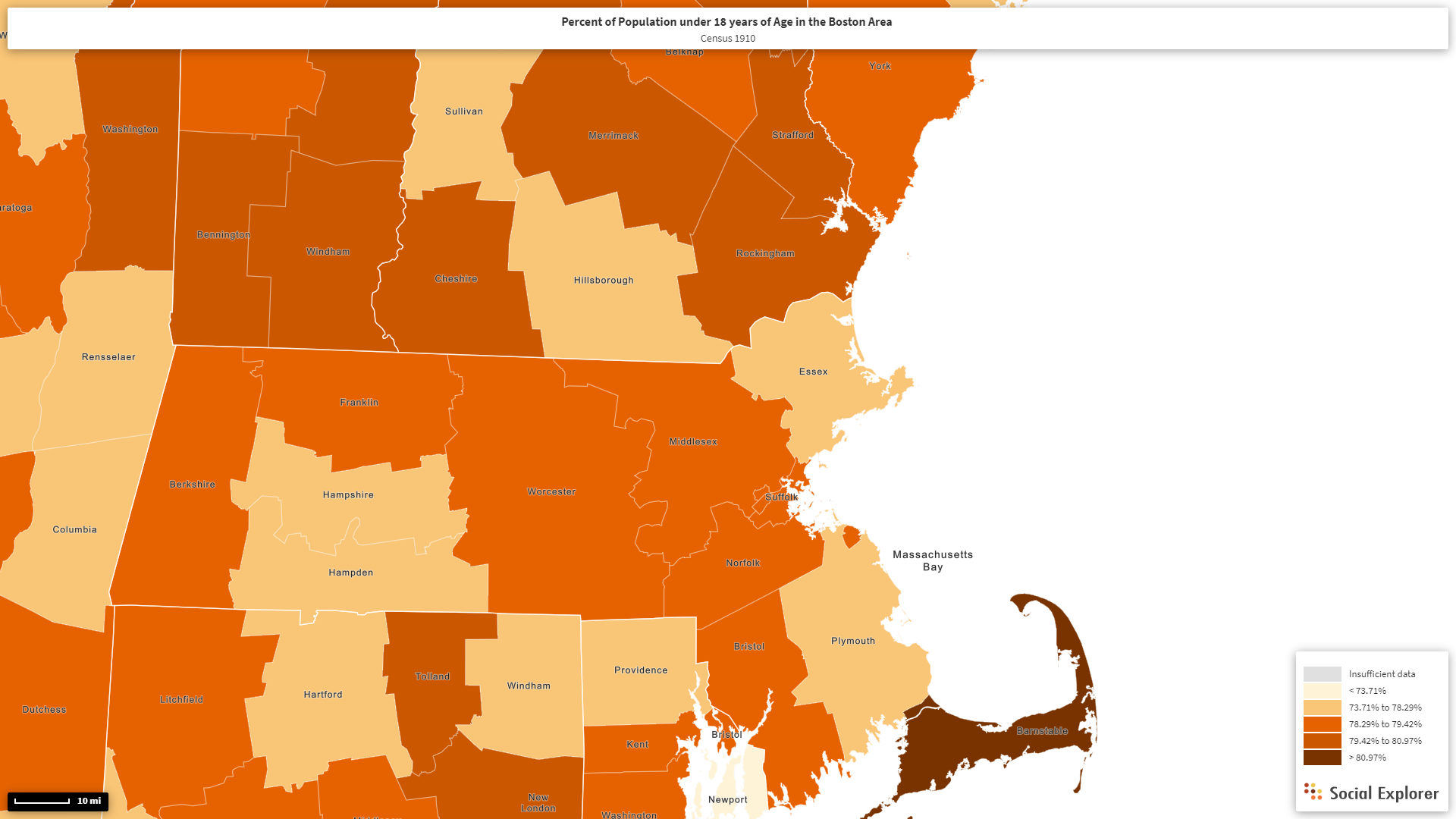

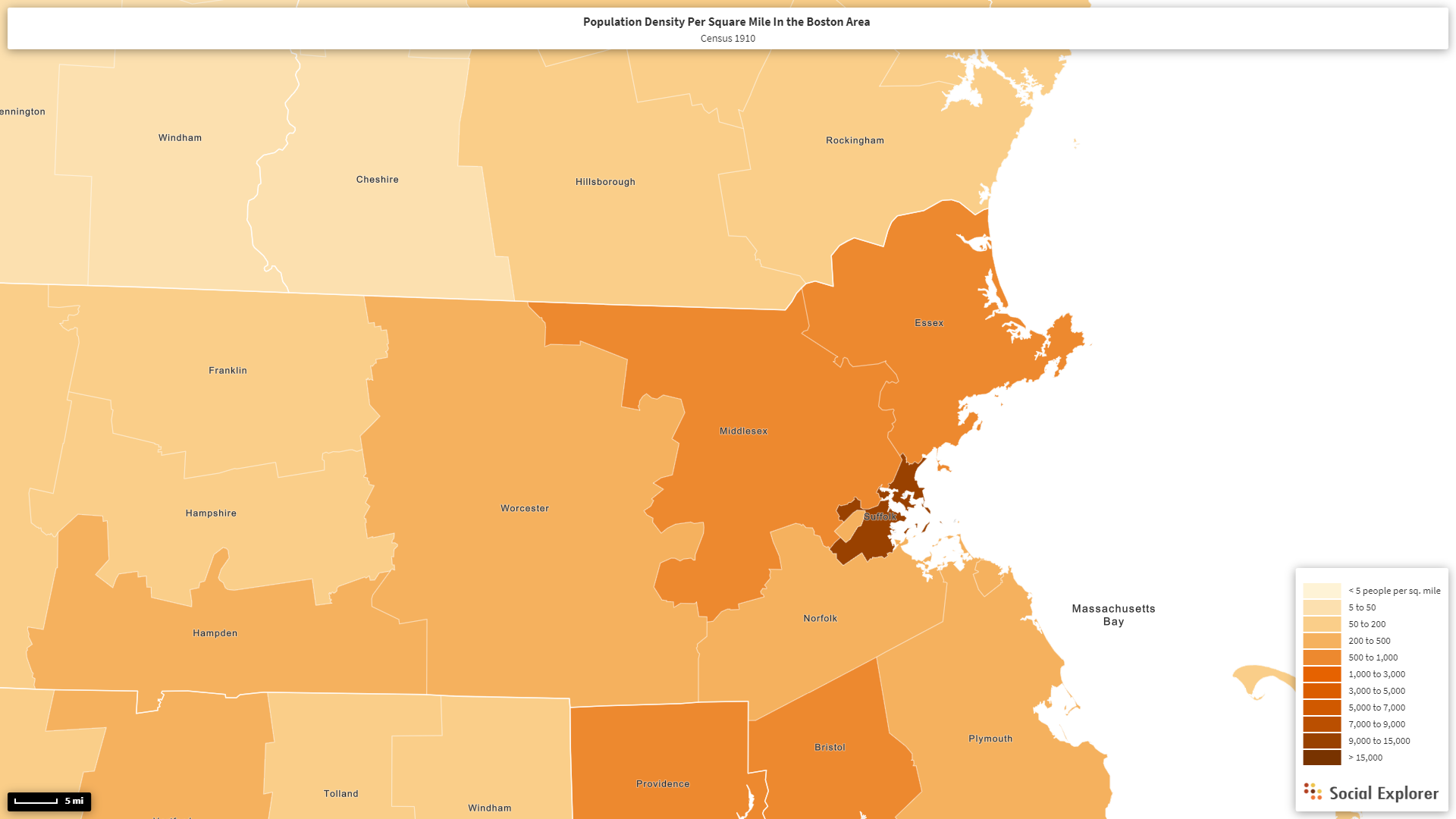

In the late 19th century many urban centers experienced growing populations which in turn increased population density at the expense of public space. As this occurred children lost access to play spaces and public spaces. Evidence of this is shown by the maps below (click images for higher resolution images). The directly map below displays the Boston population density per. square mile in 1910.

While the Boston area is among the most highly populated areas of the region what makes it stand out is the youth population shown in the second map. As displayed, the Boston area’s youth population in 1910 was the highest in the region and was also one of the most densely populated regions. which show how the Boston area in 1910 was densely populated and also had a large youth population.

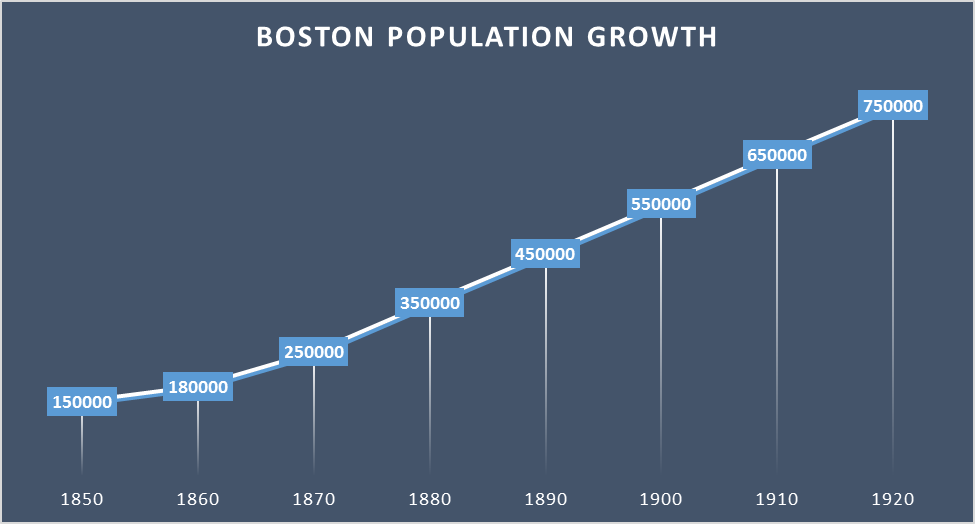

This relationship between a densely populated city and a large youth population led to a decline in urban public space including parks and playgrounds, which are typical childhood spaces. Furthermore, Boston had experienced a massive influx of immigrants starting around 1880. A Boston City Parks report published in 1925 details the difficulty of land management and maintaining access to open space with the rising population. The data from this report is created the below two graphs.

As shown in the above graph the city of Boston began a rapid expansion of its park system and eventually its playgrounds starting in around 1870. What is interesting about this data is that it shows how conscious city planners where at the time of the need for public space as well as how important physical health was to them. What we must take away from this data is that much of the impetus for maintaining and creating public space came during a time when play and play-spaces where being conceptualized as means to socialize the nation’s children in particular ways. What was happening in Boston as a reaction to decreasing open space due to rising population partly because of immigration.

Boston’s situation was probably a situation occurring in many cities across the nation. With the influx of immigrants came the fear of those immigrants and strangely play and play-spaces were partially engineered at the time to help develop a new generation of Americans out of the new immigrant population.

The 20th century in the United States “was a time of profound transition both in status of children in American life and in the role of the federal government in child policy. Childhood increasingly was seen as a developmentally distinct stage of life, and children were viewed with greater tenderness–reflecting a new, middle class belief in childhood’s importance and concern with children’s vulnerability” (Yarrow 1). In addition to legal protections, the U.S. government set out to promote the ideal childhood and how to achieve it. In 1906 the Playground Association of America (PAA) was formed and advocated nationally for the construction of playgrounds (Gagen 2000, 603). At the time playgrounds were “a common response to fears about children’s safety in ‘public’ space, and concerns for their proper rather than uncontrolled, development” (Holloway and Valentine 2000, 13). Control as well as fear of improper development were major issues at the time. Playgrounds thus offered the perfect solution as they were highly visible to the public and also could be constructed to promote certain values. A baseball field emphasized teamwork and collaboration as well as sportsmanship for example. However, playgrounds were not constructed with equality in mind. Playground construction and the formation of the PAA itself came during a time of massive immigration to the U.S. and heightened fear that immigrants and their children would erode American values. Gagen (2000) writes “supervised playgrounds were instituted across the United States as a means of drawing immigrant children off the streets and into corrective environments. Playground reformers aimed to provide a network of public, visible play spaces through which to direct the development of immigrant children towards idealized American gender roles” (Gagen 2000, 600). Where immigrant’s home spaces were seen as dirty and derelict to the point that would encourage bad behavior, playgrounds were spaces of purity, wholesome development, and most of all control. Playgrounds were pivotal in attempts to Americanize immigrant children, but also became sites of inequality and prejudice towards immigrants (Gagen 2000). At the same time, G. Stanley Hall, a prominent child physiologist developed highly gender biased theories about the benefits of play for developing strong male children who would otherwise fall victim to the emasculating urban landscape (Gagen 2000). In summation, the early 20th century was a time of urban growth that pushed many scholars at the time to develop play spaces, emphasis playtime, and begin dialogues about recess. However, these developments were laced with gender and racial bias as well as conceptions of childhood imposed by adults.

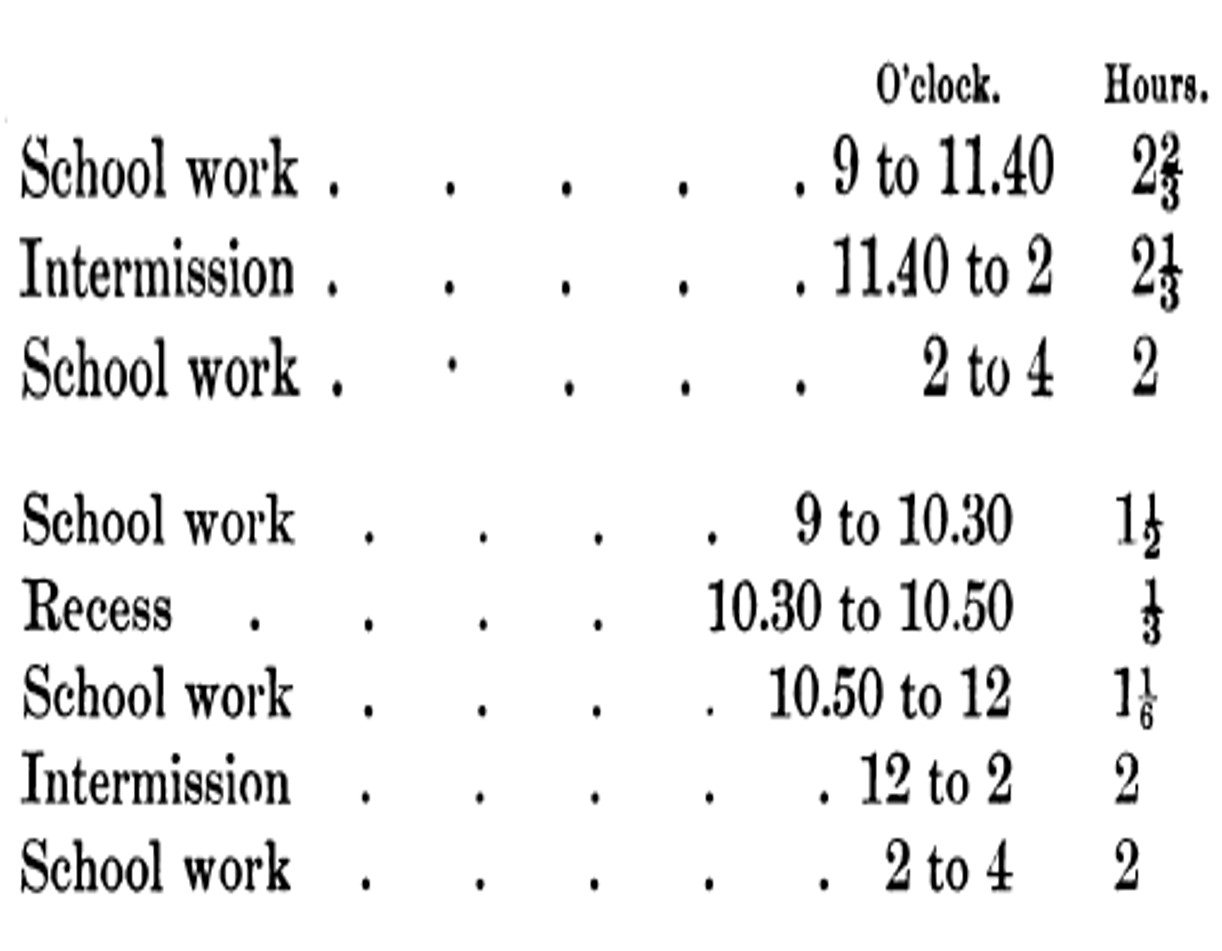

Recess functioned in much the same way as playgrounds at the time. Recess was heavily monitored and controlled and also experienced unevenly. Furthermore, recess, at its core, was designed to create an idealized school student. In school reports from Boston in the late 19th century conversations about the necessity of recess usually revolved around how recess promoted student health (Tenth Annual Report, 1890). To children recess represents a degree of freedom in an otherwise structured and disciplined world of adults. However, to adults, and to many of the early scholars on recess and playgrounds, playtime functioned as an extension of the structure and regimentation that children found in most other parts of their lives (Heck 1917). William Heck in 1917 published a report on Virginia’s school system in which he laid out the necessities of recess not only in terms of developing good health in students but also in creating a sense of unity and pride in ones school. He writes: “Marching in and out at recess is not a matter of taste, not even of convenience, but a matter of order, of co-operation, of emphasis upon group rather than individual action. Its purpose is primarily social…Children in school should become citizens of a society and merge their individualities as far as necessary into the general good…The excessive individualism in American homes, often leading to over-indulgence and self-importance” (Heck 13, 1917). That said, early debates around recess and outdoor play also focused on the various perceived health benefits of fresh air and physical exercise (The National council of Education 1885). The National Council of Education report of 1885 states: “A physician living in the State of New York treated in 1884 a girl aged eight or ten years for irritation of the neck of the bladder; this girl was attending a public school in which the no-recess plan was in operation” (N.C.E. 1885, 12). A similar debate between the “no-recess” plan and the “recess” plan was going on in Boston around 1890. The Boston school system at the time was struggling with this decision and evidence of their debate can be seen in the two proposed school schedules seen in the chart below.

The 1890 Superintendent report from Boston went into great detail around the merits of both plans. In favor of the no-recess plan the report states: “The plan affords protection to the morals of the better children by not exposing them during the recess to the contamination of those whose language and conduct are bad and whose influence is morally pernicious” (Tenth Annual Report 1890, 29). the report also states that “growing girls are saved much going up and down stairs” (Tenth Annual Report 1890, 29). This line is interesting because it is evidence of the gender inequality that Gagen (2004) describes in which boys are encouraged to develop physically into masculine American men, and girls are supposed to remain delicate, pure, and innocent. The popularity of recess in schools and the construction of play spaces occurred as a reaction to urbanization, increased immigration, and a concern for the health of children.

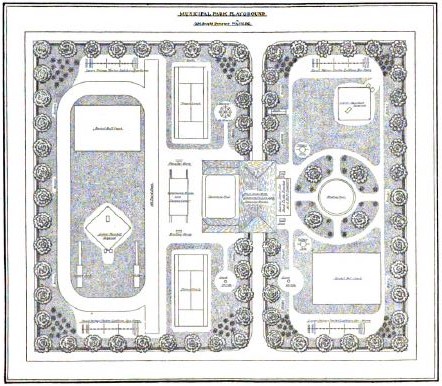

What is evident in the literature about recess and also play-spaces including playgrounds is that management of the children and the landscape is crucial. This is contradictory to the freedom that children feel and are encouraged to feel during play. In the image below we see plans for an idealized school playground (top), municipal playground (middle), home playground (bottom).

The fact that scholars at the time were mapping, planning and designing playgrounds even at this time clearly demonstrating management and organization of play itself (Rafter 1909). Rafter who published the report in which these plans were printed explained the values that would be instilled in children my playing in these highly structured and monitored play-spaces. She writes: “There seems to be an idea abroad that a playground is something unusual; a hobby, or a new fangled notion soon to die out. but it is only a matter of time and of proving up when all skeptics will see and understand that supervised playgrounds are simply the carrying out in the cities of just what has been done for ages in the homes, on the farms, or on the village green” (Rafter 1909, 5). Rafter goes on to explain how on every ‘grounds” there should be a director or teacher who “should be a trained social worker; one who understands the value of exercise and fresh air, has a fair knowledge of games and different varieties of industrial work; but above all should be chosen for his or her fitness for such a responsible position” (Rafter 1909, 5). Between having an adult director and a very created space as seen with the images that she includes above, the conception of play that she has is very regimented and targeted at developing children with the constant supervision of adults. Her ideal playground also acts as a space to forge a national identity, she writes, “There should be an American flag on all grounds, and the salute should be given every morning (Rafter 1909, 7). Much like Heck (1917) Rafter, believes in building a national identity at a very young age through recess, play, and play-spaces.

Despite freedom that children perceived themselves to posses, recess, play, and play-spaces where highly monitored spaces and practices that were designed to elicit certain responses from children. Be it enforcing gender sexist gender roles, establishing racial differences as in the case of New Orleans play spaces (Simmons 2015), or more positive goals such as fostering a healthy youth population. There is even evidence of recess acting as a way to build a national identity within young impressionable children. Much like the Americanization efforts entwined in the playground movement in the early 20th century. In 1917 William Heck like marching to recess (Heck 1917). Playgrounds were also partially created to create a masculine and American identity in children (Gagen 2000).