The invention and rise of the bicycle came at a time when America was experiencing rapid urbanization and immigration. In the twenty years leading up to World War I, eighteen million immigrants, mainly from Southern and Eastern Europe, entered the United States (Mintz 2004). At the same time, internal populations were shifting due the Great Migration (1910-1970) of African Americans from southern agricultural regions to urban industrialized regions. This section will explore how access to infrastructure that promoted bicycling was highly restricted to certain segments of the population through the inclusion of various case studies of cities as well as statistical data and personal narratives.

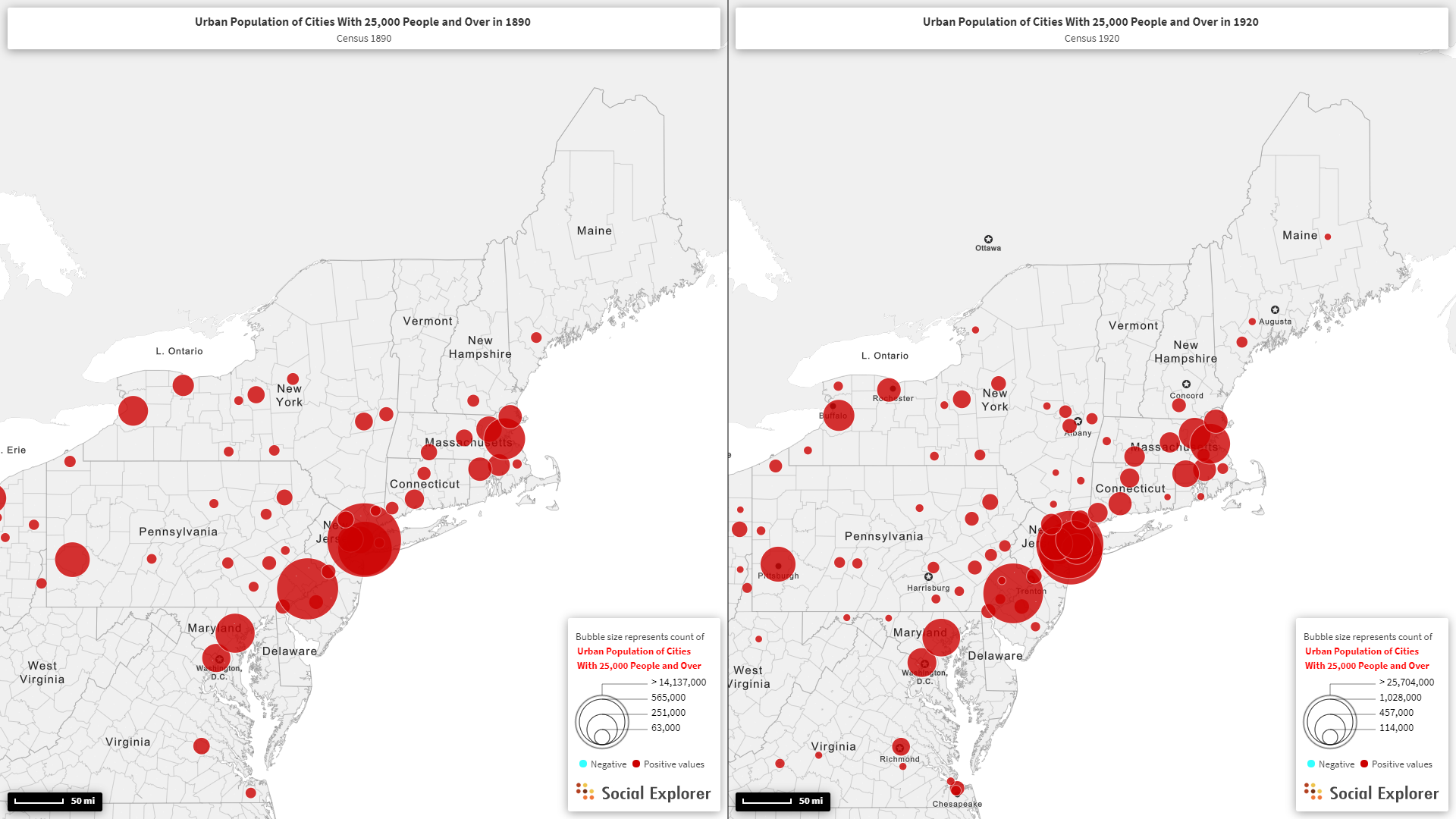

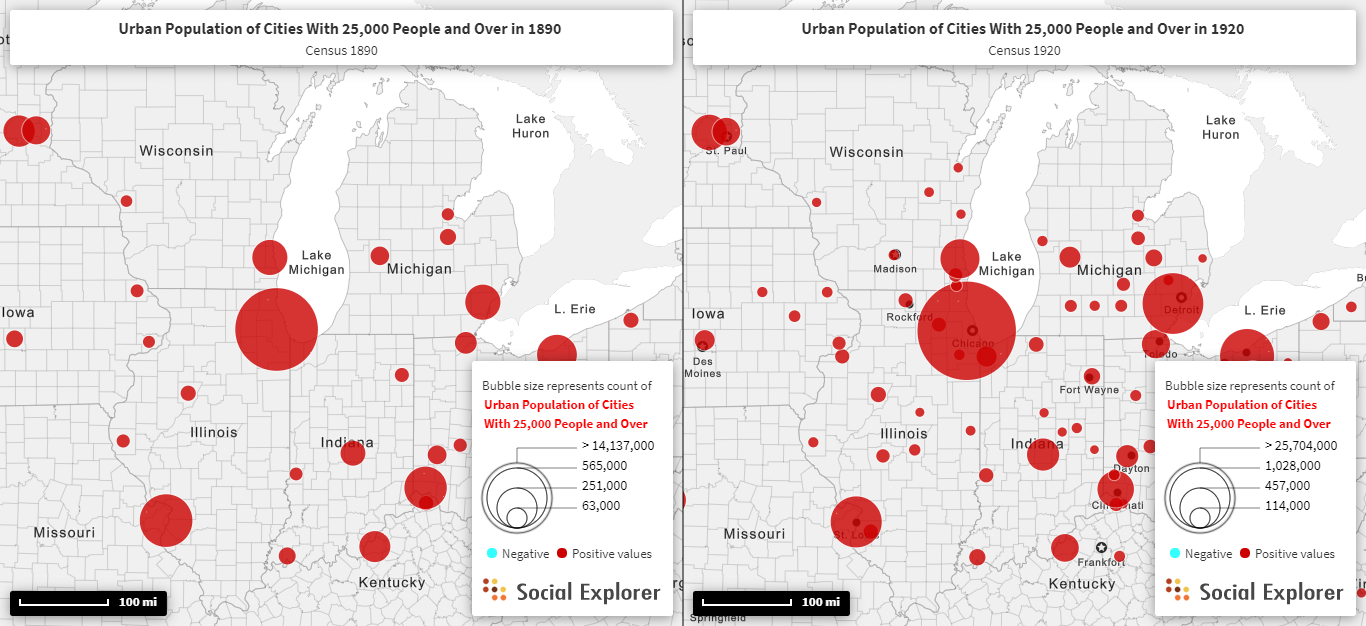

Northeast: Urban Population of Cities With 25,000 People of Over in 1890 (left) and 1920 (right)

Midwest: Urban Population of Cities With 25,000 People of Over in 1890 (left) and 1920 (right)

The popularity of the bicycle is documented in the table below which details the value of bicycles and motorcycles destined for domestic consumption in the U.S. for the years 1889, 1998, 1904, 1913, and 1919. In other words, what this document shows is the purchases of motorcycles and bicycles by families and individuals for these years. Consumer expenditure data like this can help paint a picture about standard of living changes over a period of years. These particular years showcase two bicycle booms; the large one in the 1890s and a smaller one in the 1910s as well as periods of decline following each of them.

Table 1

Value of Commodities (Motorcycles and Bicycles) Destined for Domestic Consumption

| Year | Thousands of Dollars |

| 1889 | 1,907 |

| 1898 | 27,765 |

| 1904 | 2,478 |

| 1913 | 21,850 |

| 1919 | 18,981 |

Asphalt and concrete paved roads at the turn of the 19th century were heavily concentrated in cities due to the existing financial capital larger municipalities could leverage. The map below, created by the Capital Cycling Club, showcases the asphalt and concrete paved roads in Washington D.C. at the beginning of 1884. The group was officially incorporated in 1886 and made it their mission to work with local officials on bicycle safety measures. Individuals who were a part of the Club were instructed to use bells for daytime riding and lamps for nighttime riding to reduce the chances of collision. By and large, however, most of the members were white professional men who could donate the time and money to such a cause. Such safety measures and the knowledge of street conditions for cycling, therefore, were inaccessible to children, women, working class individuals, and minorities in the late 1880s (DC Public Library).

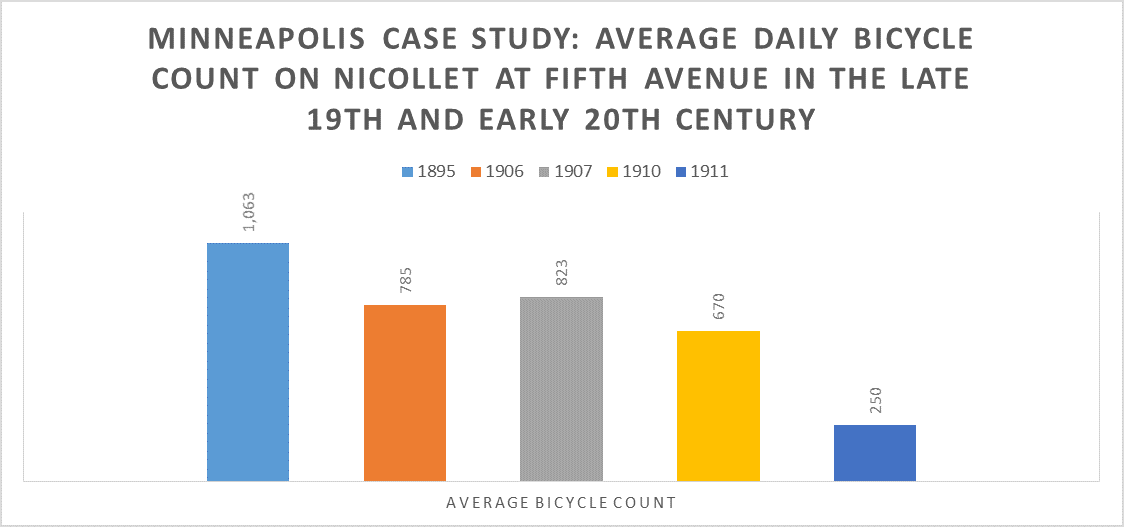

As depicted below, in Minneapolis, the popularity of the bicycle as a method of transportation and the improvement of street conditions between 1895 and 1911 resulted in the city conducting daily bicycle counts on some of the busiest streets. During this time, traffic control police officers were stationed on the roads as a result of the increased traffic. In 1895, over 1,000 bicycles were counted on Nicollet at Fifth Avenue as a average for the daily count for the month of December. As the automobile became a preferred method of transportation in the city into the early 20th century, average daily bicycle count dipped dramatically.

Note. Based on City of Minneapolis. 1986. Annual Report of the City Engineer for Year Ending Dec. 31, 1895. Cited in Petty, R. 2010. Bicycling in Minneapolis in the Early 20th Century. Minnesota History, 62(3), 84-95.

For Kathleen McKinley Harris, the experience of cycling differed depending on age and location. In the 1940s, Harris spent time in Detroit, MI and Ashtabula, Ohio. In Detroit, she rode on the sidewalks because she was not considered old enough to ride in the streets. At the age of 8, she moved to the small town of Ashtabula, Ohio and recalls living on the outskirts of town and learning to ride on the edge of the paved road because there were no sidewalks there. In both locations, most children had bicycles and she recalls riding her bike to school, back home again, and to the playground. She writes that “Eventually, we were allowed to ride as far as the corner store … about half a mile from my house …” (K. Harris, Chittenden County Historical Society, Personal Communication, December 1st, 2017).

For children, access to play and recreation space reflected differing representations of childhood and, in turn, shaped the lived experiences of such public spaces. In the community bordering the neighborhoods of Yorksville and East Harlem in NYC, children and older youth used the street as a space for enjoyment, adventure, and independence. Yorkville was a predominantly working class Irish, German, and Italian neighborhood at the beginning of the 20th century and East Harlem was predominantly a working class Italian, German, Irish, Russian, Jewish and, eventually, Puerto Rican neighborhood. In 1929, The City Club of NY conducted a study of traffic-related child deaths by the school district. Three hundred and forty deaths and almost fourteen thousand injuries were the direct result of engaging in play on the streets such as jumping on trucks, playing games in the road, and riding bicycles in traffic (Wridt 2004, 93). The report and such figures demonstrated the spatial relationship between the presence and absence of playgrounds in certain districts. It was through such studies that the concept of parks and playgrounds grew as a mechanism to prevent children from physical injury and harm related to play on the streets. In the 1930s and early 1940s, New York City experienced a dramatic increase in public play spaces – an 100% increase in parks, a 225% in playgrounds, and a 1000% increase in swimming pools (Wridt 2004, 94). However these new play spaces were spatially concentrated in wealthier neighborhoods.

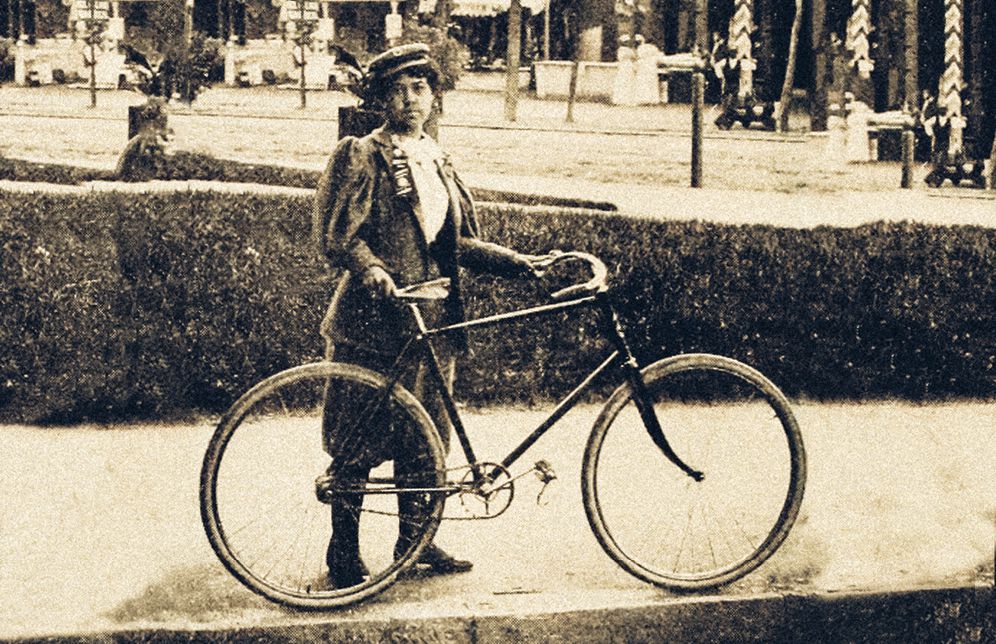

Similar political campaigns involving cycling helped ensure that minorities, women, children, and the lower classes would largely be excluded from using bicycles in public spaces and that the fight for better infrastructure for cycling would be geographically concentrated in particular cities and neighborhoods. The L.A.W. was formed in 1880 and they made it their mission to fight for the use of bicycles in public spaces such as Central Park in New York City and demand national and local government to take responsibility for the condition of roads (Finison 2014). However, in 1894, the League instituted a color bar – restricting membership to whites – and thus ensuring that African Americans could not participate in most bicycle races at the time (Finison 2014). Despite this restriction, African American cyclists continued to go to whites-only League meetings and races. Kittie Knox, a bi-racial young seamstress, became known as an activist in the late 19th c. Boston social cycling scene when she started winning races, showing up to the “whites-only” national cycling meetings, and sporting her hand-crafted knickerbockers. She was a part of the Riverside Cycling Club, the first black cycling club in the nation (Finison 2014). The club relished the ability to escape the urban landscape of railroads, housing, factories, storefronts and the associated pollution and smell concentrated in the West End, the prominent African American neighborhood in Boston at the time. The club traveled to the outskirts of the city on “tours” and often encountered discrimination at public accommodations such as inns and food establishments (Finison 2014).

Story Map of A Few Major Historical Developments of the Bicycle

Kittie Knox at Ashbury Park (n.d.) Courtesy of Smithsonian Library.

Additionally, the bicycle directly challenged the notion of ‘separate spheres’ for men and women by allowing women the physical ability and freedom to escape the confines of their traditional “home” space. The appeals of women losing ‘natural femininity’ and associated physical characteristics were used to regulate women in regards to their dependent role in the private sphere and virtually non-existent role in the public sphere. The ‘feminine ideal’ was based on the belief that woman were devoted to their husbands and accepted their submissive role in the home as their ‘only’ proper sphere. Additionally, according to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a prominent figure in the women’s suffrage movement, the bicycle provided the perfect opportunity to “… escape the closed atmosphere of the brick-and-mortar church and to seek instead spirituality instead in the open and balmy air” (Strange & Brown, 2002, 621). To Stanton and many others, the bicycle became a mechanism for spiritual and religious liberation from the traditional Christian state in the late 19th and early 20th century. The vehicle could offer individuals a sense of freedom, solitude, and relaxation outside of the confines of the expanding urban jungle. This influence on women trickled down to young girls and influenced the types of gender roles they were subjected to in regards to physical activity, mobility, and independence. As woman challenged societal norms through cycling, new avenues opened up for young girls to experience their everyday geographies and identities in a whole new light.

For boys, the First World War had created a unique opportunity to market bicycles as a way for them to increase their health, individual mobility, strengthen their patriotism, and exert their masculinity (Turpin 2015). Since juvenile masculinity was seen as the transition period between boyhood and manhood, the usage of the bicycle was seen as a transitional period between pedestrianism and auto-mobility (Turpin 2015). These beliefs became imprinted on the landscape through the road reform movement. This reform was largely directed at rural areas and promised more efficient services (such as mail delivery and trade) and better access to public institutions such as churches and schools (Vogel 2010). This accelerated urbanization and thus expanded children’s access to “country life” as well as low-income individuals and minorities.