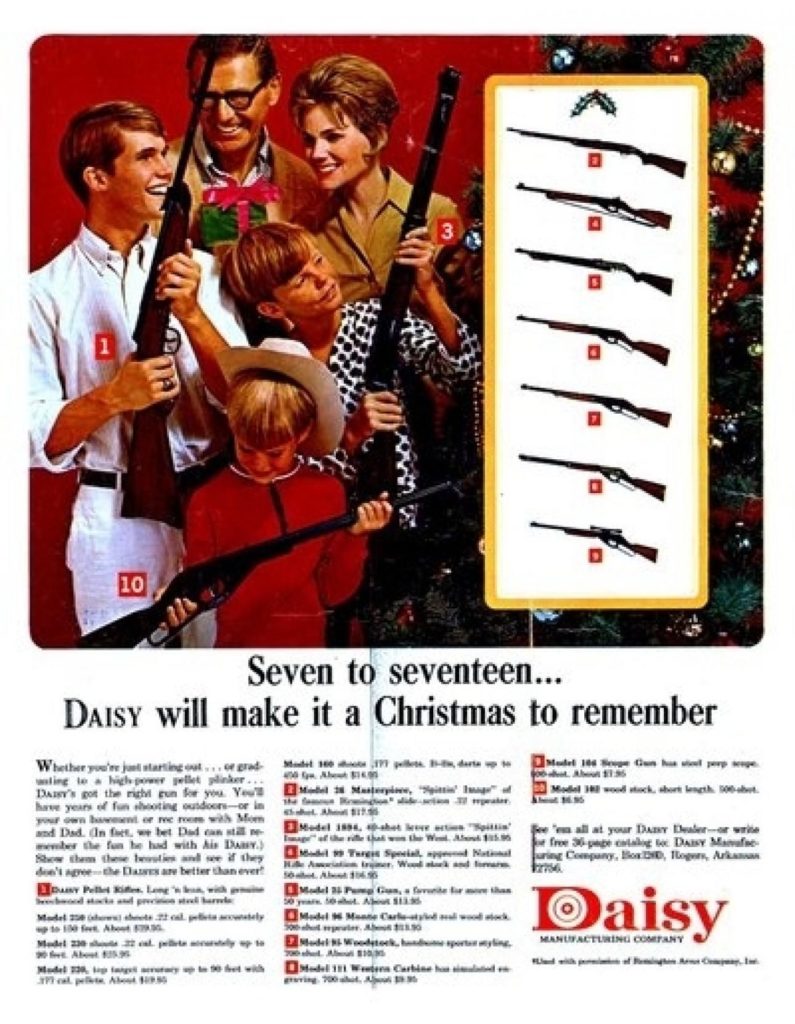

Daisy Rifles Advertisement Sears Roebuck Co. Catalog. (1950).

Firearms as an object in the history of North America have had a number of different identities. Firearms were seen as tools with which individuals could hunt, manage pest, protect property, and deter crime. In rural, areas boys were required to learn to how to properly use firearms as a necessity of life (Brown 2012). Hunting and the creation of the young outdoorsman, in turn, reflects certain values of American exceptionalism through hunting. During the late 19th and early 20th century, Americans viewed hunting as a representation of their greatness, in doing so, childhood heroes were created. Boys and young men alike began to idolize the totting frontiersman and elite outdoorsman (Herman 2014).

The growth of the material culture with the industrialization of the United States during the turn of the 20th century drove firearms to become an object of status as well as an object of sport. Mass production of guns and ammunition made firearms more affordable as a result. As this occurred, the prevalence of firearms in households began to grow across North America. With material culture, marketing of firearms became more dominant in everyday life in society. The Sears Roebuck Catalog began marketing their firearm stock to families, most prominently men and boys. No longer were firearms only being used as a scarcely available survival tool. Boys began shooting for recreation in the areas of trap, sharpshooting, and sport hunting. In some cases, young white girls were encouraged to take part in shooting sports by figures, such as Annie Oakley. This promoted the creation place for young girls as outdoors women (Glenda 1995).

Disparities began to emerge and with them, people became more aware of the racial differences that were present in the realm of firearm ownership. Racial disparities in firearm ownership were widespread across the continent. The accessibility of firearms was strongly influenced by the issue of race. African-Americans had minimal access to both firearms and to the field of the outdoorsman. Primarily, African-Americans were allowed to join hunting outfits but to the limited role of cooks and field servants (Swanson 2010). Gun ownership primarily took place in the Northern United States among the high concentration white middle to upper-class households there. African-Americans often rejected gun ownership and the outdoor figures that go along with it making gun ownership a white-dominated field (Herman 2014).

| Recorded Homicides, 1915-1950 | |||||

| Year | Total Deaths | Male Deaths | Female Deaths | Deaths by Firearms | Percent Caused by Firearms |

| 1915 | 15,374 | 12,178 | 3,196 | 9,181 | 59.7% |

| 1920 | 23,820 | 19,079 | 4,741 | 15,848 | 66.5% |

| 1925 | 35,857 | 28,843 | 7,014 | 25,944 | 72.4% |

| 1930 | 45,594 | 36,581 | 9,013 | 30,977 | 67.9% |

| 1935 | 56,094 | 45,364 | 10,730 | 37,147 | 66.2% |

| 1940 | 47,823 | 38,011 | 9,812 | 28,077 | 58.7% |

| 1945 | 37,123 | 29,301 | 7,822 | 20,277 | 54.6% |

| 1950 | 41,202 | 32,174 | 9,028 | 23,046 | 55.9% |

| Average | 43,270 | 34,504 | 8,765 | 27,214 | 62.9% |

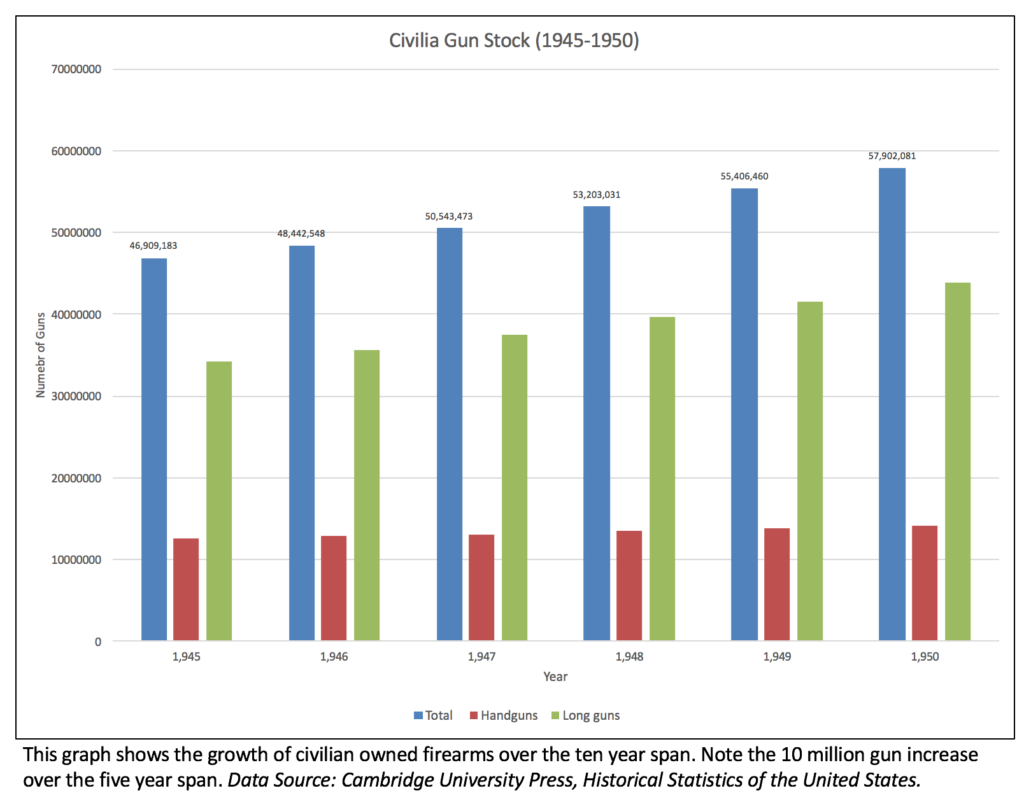

Gun stock in North American home’s rose continuously through the early 20th century. Between the years if 1945 and 1950 alone civilian guns stock rose by 10 million firearms, from 46 million guns in public possession to 57 million. A staggering increase in firearm ownership for the time period. Primarily contributing to this was the rise of long rifle ownership following the growth of shooting sports among the white middle to upper-class. This growth was significantly higher than that of handguns. Firearm ownership occurred, most substantially in the Northern portion of the United States where the largest percentage of white Americans were located. The heightened accessibility that white Americans had to firearms over African-Americans shaped the greater distribution among households in the greater country. With the growth of the firearm accessibility and possession, there has also an inevitable increase in the number of firearm-related deaths from 1910 moving forward throughout the 20th century. By 1950, firearms would make up 190,497 deaths in all together. From 1915 to 1950, firearm-related death accounted for nearly 63% percent of homicides that occurred in the United States.

Further examination of the timeline of the changing perceptions attached to firearms.