About three weeks ago, my family and I purchased bicycles. For me, the purpose of having a bicycle is obvious: riding one–to and from my work at the Universidad Nacional, running errands, etc.–is a form of participant observation. Having the actual experience of riding around helps me better understand what others tell me about it: the mundane frustrations, the excitement, the marginality, the feelings of moral righteousness as one passes automobiles snarled in traffic jams, the experience of taking it for repairs, and so on. The issues are complex and subtle.

Here is the bicycle I bought. I set it up as a utilitarian urban bike, with fenders and a rack:

For my family, on the other hand, having bicycles is pretty much solely for a recreational purpose: to ride them in Ciclovías, the Sunday morning tradition–a “rolling parade” as someone called it–here where numerous streets are closed to automobiles and people come out in droves to ride bicycles, walk, rollerblade, etc. as seen here with my son: Depending on where you buy it, purchasing a bicycle can be quite different from buying a bicycle in the U.S. There are some shops, mostly in the middle-class and wealthy northern part of the city, that sell mid-level and high-level imports (Specialized, Trek, etc.) and the layout of the shop, the selection of bicycles, the interaction with an attendant–and the prices–are similar to any of the some 4,000 shops you’d find in the U.S. But there are other shops–the majority–that are densely-packed, small-scale businesses where Bogotanos shop for bikes and parts that are concentrated next to each other in a few locations around the city. It’s bit like how retail is clustered in New York City: if you want to buy restaurant equipment, find the neighborhood where it’s sold and you’ll find a bunch of shops next to each other. So it is with retail in Bogotá.

Depending on where you buy it, purchasing a bicycle can be quite different from buying a bicycle in the U.S. There are some shops, mostly in the middle-class and wealthy northern part of the city, that sell mid-level and high-level imports (Specialized, Trek, etc.) and the layout of the shop, the selection of bicycles, the interaction with an attendant–and the prices–are similar to any of the some 4,000 shops you’d find in the U.S. But there are other shops–the majority–that are densely-packed, small-scale businesses where Bogotanos shop for bikes and parts that are concentrated next to each other in a few locations around the city. It’s bit like how retail is clustered in New York City: if you want to buy restaurant equipment, find the neighborhood where it’s sold and you’ll find a bunch of shops next to each other. So it is with retail in Bogotá.

So when we decided to buy our bicycles we chose one of those bike shop areas, a neighborhood called 7 de Agosto (around Calle 68 with Carrera 28), where there about two dozen shops.

One of the striking things about the shop we chose–and it is not unusual in the mainstream shops–is that the attendants were women. My wife responded positively, contrasting it with her experience in U.S. bike shops where she says she feels alienated by the masculinity and tech-heavy vibe. Here she felt welcome because the women we interacted with–the shop attendant who helped us pick our bikes, the woman behind the counter who handled the financial transaction–were asking about who we were, what we were doing here, how our kids (who were with us) were adjusting to life here, sharing with us suggestions about where to eat lunch nearby, etc. I asked the woman behind the counter why it was so common for women to be in the bike shop business and she explained jokingly, “Because we’re so much more intelligent and careful with money than men!” Many bike shops are family-owned and you’ll see spouses working together and their kids playing around the shop. Except for the high-end shops I’ve visited, one gets the sense that bike shop employees and owners are not “cyclists” as they often are in the U.S., that is, bike enthusiasts who identify themselves closely with bike culture and events. Here, the bicycle appears to be just another commodity to sell.

We bought the cheapest bicycles possible, Colombian-manufactured mountain bikes, for about $75 each. At this level, bike sizes don’t really vary so the process of picking a bike is not around sizing but which color or substitutions you want (front shocks, higher end shifters, etc.)–they’ll pretty much compose the bike you want. We didn’t test the bikes at all–lack of trust in strangers is a pervasive feature of life here, and it didn’t seem conceivable at this mid-to-low-end shop to even ask to try the bikes out on the city streets out front. One result is that it is very common to see people riding bikes that clearly don’t fit them, usually because the bikes are too small. When we made the purchase, they did not push accessories on us which I’ve seen is common in shops at home (locks, tools, fenders, etc.).

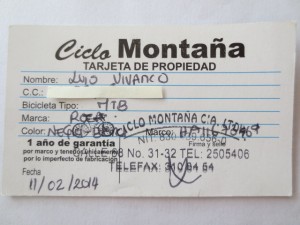

One of the important issues to get squared away right off the bat once you pay for a bike is for the shop to issue our “proof of ownership” card. Here’s mine:

Bicycle theft is a big problem here. One measure to deal with it–mostly ineffective at combating the problem, according to my friends in bicycle circles–is that police can stop you while you’re on a bicycle and ask to see your proof of ownership card. They have the ability to confiscate the bicycle if you cannot prove you own it. And apparently they do actually confiscate bikes, in big quantities, to the point that I’ve heard there is a huge mountain of bicycles in a police yard somewhere in the city where all the confiscated bicycles reside.

March 9, 2014 at 10:05 am

[…] By Luis Vivanco […]