A few years ago I read an article called “The anatomy of a reliable, everyday bicycle” on the Holland-based bicycle blog “A view from the cycle path” (http://www.aviewfromthecyclepath.com/2009/01/anatomy-of-reliable-everyday-bicycle.html), in which the author describes the normative qualities of the prototypical Dutch bicycle. It is a vehicle built for the purpose of mundane practicality and rider comfort in the cycle paths and cycle tracks of that country’s cities and towns. It is characterized by an upright posture, racks and baskets for carrying things, minimal gearing, enclosed chain, etc. In the U.S., at least, the Dutch-style bicycle has been enjoying an upsurge of popularity given its utility, upright posture, and stylish good looks though it’s still fairly unusual to actually see one.

So what is the “anatomy of a reliable, everyday bicycle in Bogotá? It’s quite different here…

Practically any time I leave my apartment, I see bicycles being used for everyday transportation. They are ubiquitous in this city. But they are also heterogeneous. There is no single or normative “anatomy of a reliable, everyday bicycle” because there are many bicycle types, adapted for different purposes and the variable needs and conditions of the rider. If the sometimes contorted bodies of riders sitting on bicycles that appear too small for them seems to suggest, “comfort” doesn’t always seem to be a major priority of every rider here.

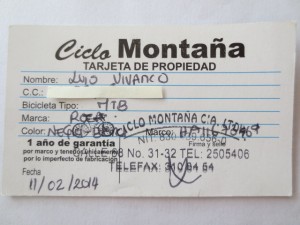

For low-income riders–the vast majority of bicycle riders here in the city–a major priority is affordability, as well as durability on city streets with irregular surfaces, potholes, rocks, litter, fragments of brick, and the general flotsam and jetsam of urban waste. So inexpensive mountain bikes (Colombian-made) with knobby tires are very common, such as the blue bike in the foreground. Some of them, such as this one, are outfitted with front shocks for dampening the impact of irregular surfaces.

Such bikes may, or may not, have fenders and a rack. Maybe a blinky light, but not always. Backpacks and plastic bags hanging on handlebars are considered practical.

There are some imported inexpensive everyday bicycles, some of these are Indian-made “gentlemen’s bikes” (known here as turismeros, or touring bikes):

Another category of everyday, reliable bikes are work bikes, which are also common here since many deliveries are made on bicycle. They come in all shapes and sizes:

As you move up in class status, ideas about reliable, everyday transportation shift. For many people who can afford them, an imported folding bike such as a Dahon or Tern with rack, fenders, and hub gears is considered highly practical not just because it can carry panniers but because it can be brought inside instead of left outside for bike thieves to grab. Folding bikes are fairly common among bike advocates, who are serious about their investment and the utility of their bikes:

“Reliability” is a relative concept too, especially when it’s fairly easy and inexpensive to get your bike repaired on any given Sunday at Ciclovía, where bike mechanics set up temporary shop along the sidewalks to repair bicycles.

The bikes above are the not the only bikes one encounters in everyday use; there are the others one sees out there on the streets, including ten-speeds, the fixies (especially popular among young men), even road racing bikes. The diversity of bicycle types reflects the social heterogeneity of the people who ride them, and the specific conditions in which they bicycles are likely to be ridden.