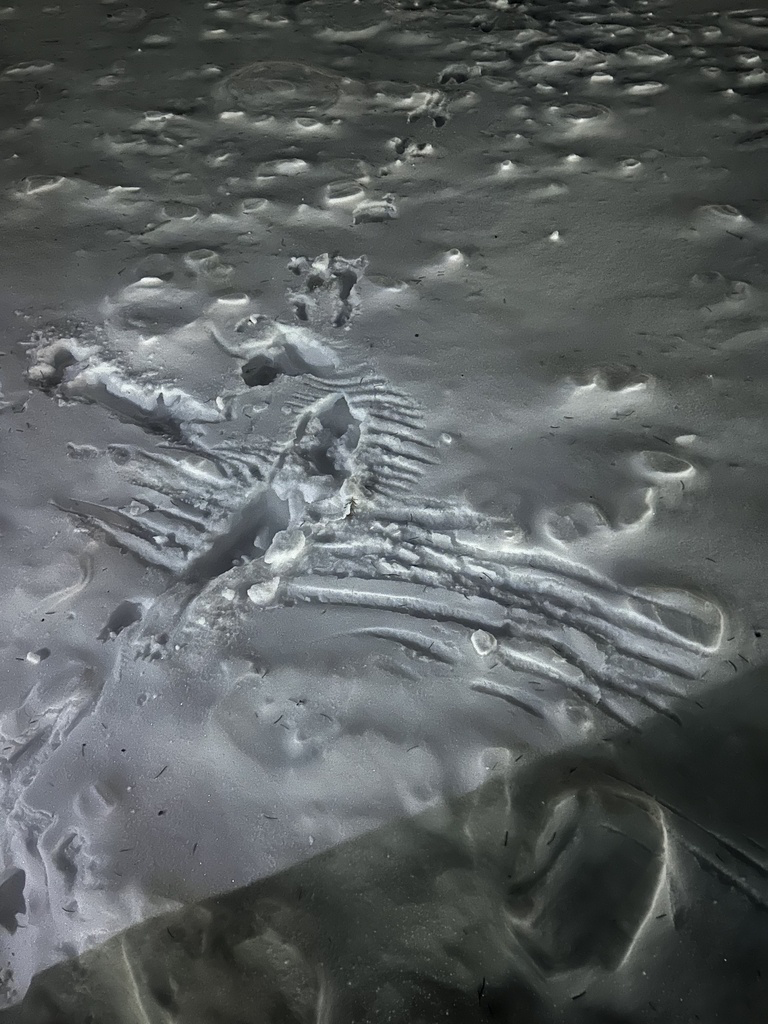

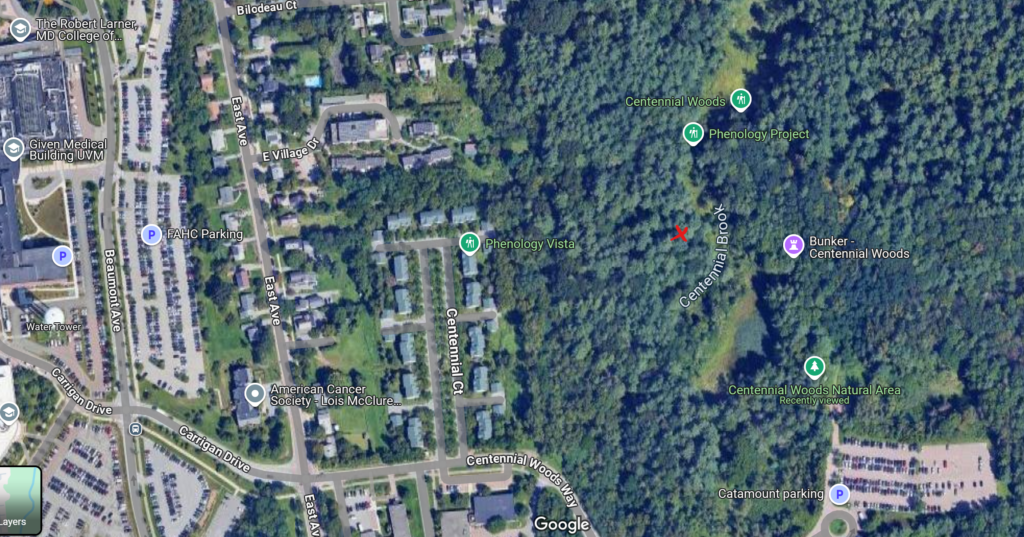

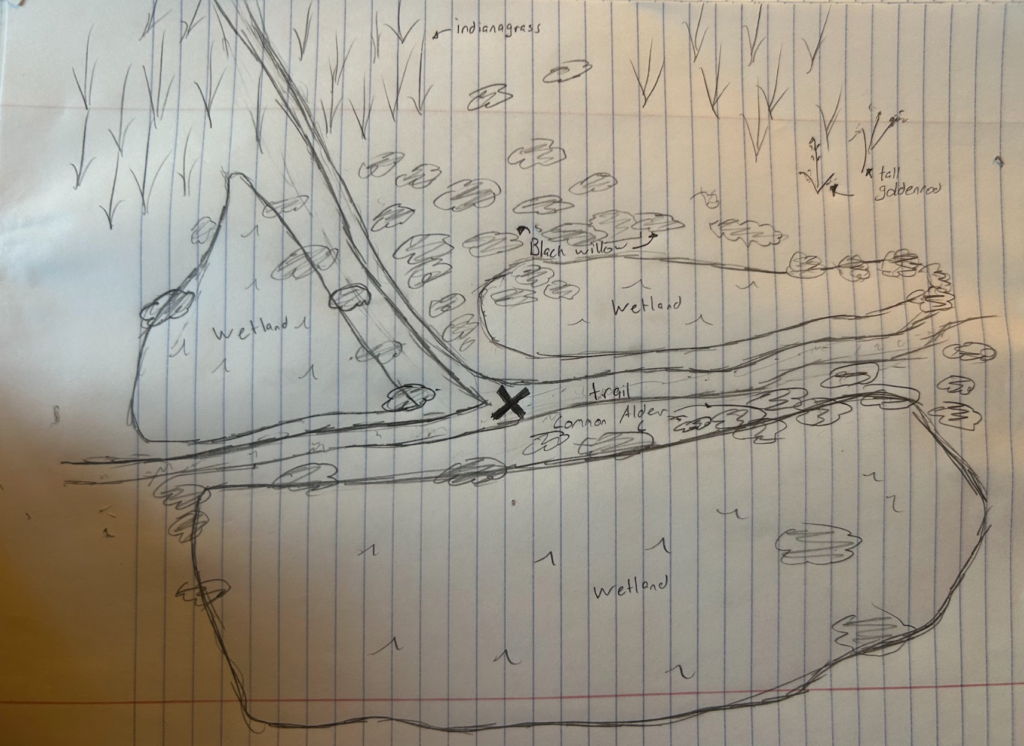

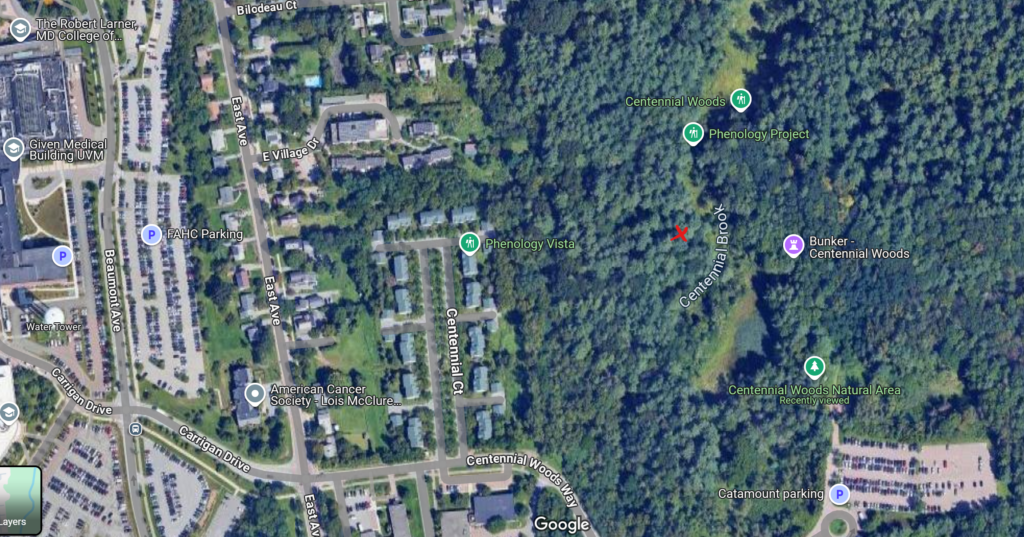

On March 31, I went out to collect my data for the phenology walk.

Generally, it appeared that all 5 trees were in a dormant phenophase, with no buds breaking, flowers, expanded leaves, or pollen visible.

Looking at the National Phenology Network’s website, something that sticks out to me is how spring started earlier than average in some places in the US, but later in others. Spring tended to be arriving later in northern states, like Vermont, and earlier in southern states, a development that is likely related to climate change. Thinking back to our phenology guest lecture, I wonder if this could represent phenological mismatch, where phenophases that are meant to occur in sync will become disjointed, disrupting ecological processes. For example, a lot of birds migrate through Vermont in the spring, but if spring occurs earlier in the South and later in Vermont, is it possible that the birds could migrate too early and not have enough food?