Properly managing stormwater in cities is a major challenge. Cities are almost entirely concreter, asphalt, tar, or shingles; none of which is particularly. This broad impermeability is compounded by decades of centralization in the form of gutters which lead to a central sewer. Unfortunately in many cases, this same sewer system handles waste from toilets and sinks, so when the sewers overflow in heavy rains, raw sewage spills out onto streets and into public waterways, presenting a mammoth public and environmental health issue. The final complicating factor is that major sewer overhauls are expensive and difficult. Solutions then, must be simple, diffuse, inexpensive, and above all, effective.

The city of San Francisco’s Stormwater Design Guidelines outlines seven goals that an ideal project would attain:

- Do no harm: preserve and protect existing waterways, wetlands, and vegetation

- Preserve natural drainage patterns and topography and use them to inform design

- Think of stormwater as a resource, not a waste product

- Minimize and disconnect impervious surfaces

- Treat stormwater at its source

- Use treatment trains to maximize pollutant removal

- Design the flow path of stormwater on a site all the way from first contact to discharge point

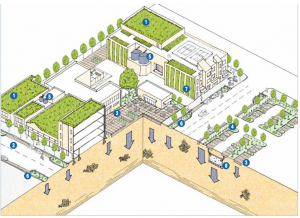

These ideas are simple and powerful, and expand upon the general ideas of Slow It, Spread It, Sink It, Grow It. Because of the diversity of sites found in cities, in terms of underlying slope, amount and type of area drained and available, and complex interactions between buildings, a huge diversity of different strategies and structures can be employed. Starting at top, rooftop gardens and other vegetation slow and retain water and allow plant roots to both filter and absorb water. Downspouts are routed into cisterns, barrels, or through rain gardens or biofiltration swales. Permeable pavements infiltrate water into native soils or into cisterns for storage and non-potable uses. Curb cuts can allow water running along gutters to flow into planters or other systems. These combined systems all enhance the capacity of traditional stormwater treatment methods by reducing the amount of water reaching storm drains, and pre-filtering water that does arrive. These systems also have the ability to buffer extreme rain events, by quickly absorbing water and slowly releasing it to the storm drain system, minimizing peak flows. The key is to get water to pass through as much soil, roots, sand filters, or other elements before reaching the traditional stormwater system. Finally, nearly all of these types of improvements also make cities more live able for people and wildlife. Rooftop gardens, bioswales, more trees and grasses, more-permeable surfaces provide insect, bird, and mammal forage and habitat, while making cities cooler, cleaner, and more beautiful for the people who live there.

-Brian Thompson

You can read the executive ‘summary’ of the San Fransisco Stormwater Design Guidelines here:

http://www.sfwater.org/modules/showdocument.aspx?documentid=2779

And if you get real jazzed up, also find the City of Seattle’s 500+ page Stormwater Manual: