Introduction

Centennial Woods is a 65-acre natural area nestled between Burlington and South Burlington. Primarily Forest and Marsh, Centennial Woods is home to many species of forest and fauna. Only a few hundred yards deep into the forest trail beginning at 280 East Avenue sits a small stream and muddy bank keeping the small marsh divided from the forest. Serving as an apt microcosm of the overall Centennial Woods ecosystem, this stream and the immediate surrounding area will serve as the focus of this blog.

This area of Centennial was chosen for multiple factors. Like previously stated, this stream serves as a microcosm of the greater Centennial Woods ecosystem. Additionally, this area is very near my dorm, making it very accessible for frequent visits throughout the change of the seasons.

^ A wide view of the steam bank (covered by fallen leaves)

^ A panorama of the greater stream, and many of the tree species surrounding it.

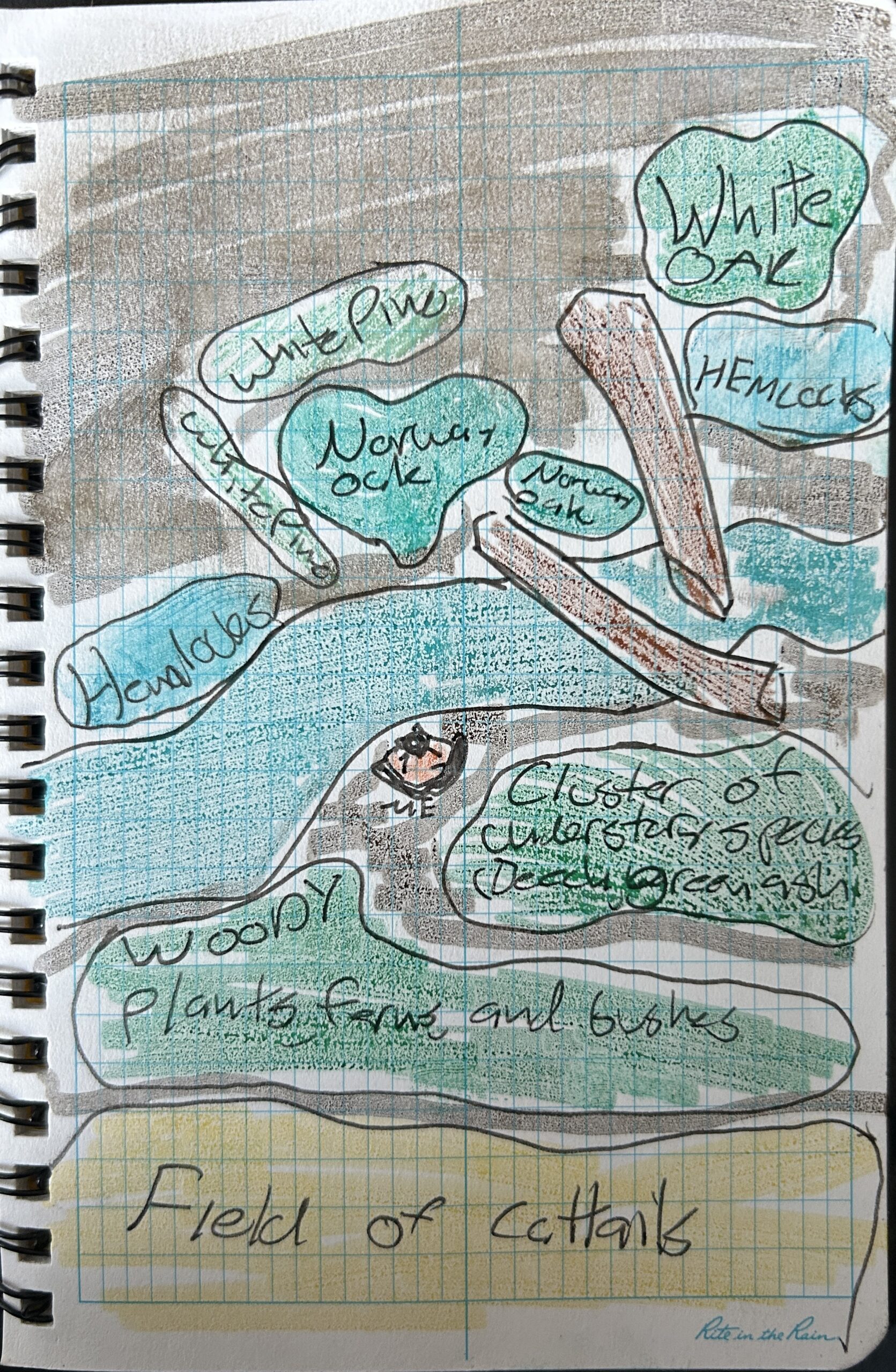

The vegetation of the stream is characteristic of much of Vermont, with many staple species present. the understory and overstory are equally covered in Red Maples, White Pines, Norway Maples, with the overstory containing a very large and old White Oak in particular. The bank of the stream is covered in Hemlocks and Green Ash.

15 Minutes Sensory Engagement and Birds’-Eye View

Today, on November 5th, I sat down on the bank of the stream opposite tot the great white oak (the same spot as the panorama is taken) and spent 15 minutes observing my surroundings. Here are my observations.

I noticed firstly the gentle trickle of the stream water right in front of me, while leaves rustle periodically in the wind and break away from their branches and drift to the forest bed, adding to the blanket of dead leaves covering the ground, much of it muddy right along the stream. I smell the organic moisture of the river, but mostly just the crisp cold in the air. Around me is a healthy mix of trees completely barren of leaves, fiery orange trees still holding onto their last few dozen, and trees inexplicably still green despite the changing season. Most species are white oak, beech, and different types of maple. There is a notable cluster of white pine, however the only other conifers are the many understory eastern hemlocks that cover the bank. Birds faintly chirp in the distance, however the many bugs previously dominating the area have all gone away, and there is no sign of the multiple squirrels I observed traveling across the upper branches in the earlier month.

A Bird’s Eye view of the Centenniel Woods microcosm

Changes in the Ecosystem

Since my previous visits, much has changed. The last time I visited the area was in mid October, and since then many more trees are bare, and leaves now blanket the entire woods. In addition, the fauna seemed less prevalent. I saw no squirrels compared to the last visits, where I would see 1-3 of them around the stream up in the trees. Interestingly, there was what seemed to be large scat of some large animal on the trunk that lay across the stream. I doubt it was dog (that would be pretty impressive), so it’s possible a deer or perhaps even a young moose traveled across the natural bridge not too long ago.Generally, it seems the deciduous trees are beginning their slumber for the winter and the mammals seem to be joining them.

Phenology of Miles Standish State Forest, Plymouth, Massachusetts

For November break, I have returned back to my hometown of Plymouth. While I have spent the break enjoying time with my family and a reunion with my old friends, I also spent a day in the Miles Standish State Forest, covering a substantial area pinched between Carver and Plymouth, and about a mile from my house.

The 12,400 acre forest’s community makeup varies across the forest, containing marshes, pine barrens, and wetlands. None of it resembles very strongly the makeup of Vermont, at least as far as I’ve seen. The spot of the forest I spent my time in was itself likely a pine barren.

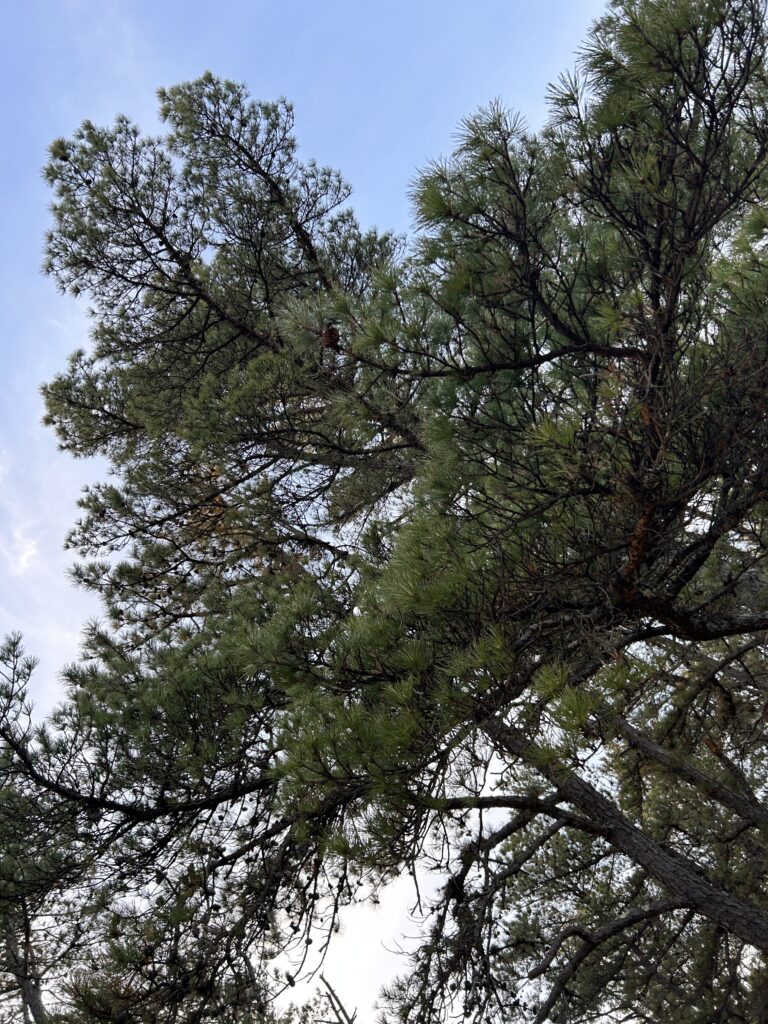

Pine Barrens are one of the rarest ecosystems globally, and only a handful exist today. one Pine Barren is in Tidmarsh, a wildlife sanctuary also in Plymouth, while another is in New Jersey, and the last one is in the Myles Standish State Forest. Pine Barrens are characterized by highly acidic, sandy, low nutrient soils, and frequent forest fires. What is so interesting about the Pine Barrens ecosystem is its relationship with fire. through both exposure to Native American controlled burns as well as natural forest fires, species of the Pine Barrens have evolved to capitalize on the frequent disturbances. For example the Pitch Pine, the dominant tree species in the ecosystem, has thick fire-resistant bark, and serotinous pine cones; pine cones covered in a thick resin that must be melted away before the seeds can be spread.

A Mature Pitch Pine

A wider shot of the Pine Barrens. it was a particularly pretty golden hour that day.

Pine Barrens used to be widespread along the east coast, even covering most of eastern Massachusetts. Following European settlement, fire control caused a sharp decline of the ecosystem, until it shrank to only a few remote remaining spots.

This particular Pine Barrens is likely a very young stand. Note the even spread of the skinny Pitch Pines- competition must be fierce for the trees right now.

The most prominent tree species were

- Pitch Pine

- Eastern White Pine

- Red Pine

- Norway Spruce

There wasn’t a deciduous tree for as far as I could see, which is consistent with the rest of the state forest. Unlike Vermont, Maples and Oaks don’t have a very strong presence in the State Forest.

This spot is very special, both personally, as I spent a lot of my after school days in the state forest, and ecologically, as it is home to a critically endangered ecosystem.

Compared to my phenology spot in Burlington, the pH and the nutrient composition at the Plymouth phenology spot is probably much lower, as is the trend of Pine dominant stands, only even moreso. The Phenological trends of the Pine Barrens is probably less stark than that of Burlington, as there are much less deciduous trees with leaves to color the canopy or blanket the forest floor.

Final Blog Update of the Semester: Winter slumber

Today, on December 9, I made my final visit to the small stream of Centennial Woods for the semester, and it is definitively now winter for the small forest. Not a leaf remains on any of the deciduous tree, and the white pine needles are just about alone on the forest floor, the vast majority of the leaves that used to blanket the ground are decomposed to dirt. The dense canopy of the large white oak is now a gnarly tower reaching into the sky, looking almost like a lightning strike that reached up from the ground and was petrified into wood (seriously white oaks look super cool). There is no longer any presence of animal life, as all the bugs that inhabited the forest have now gone with the leaves, and there is no evidence of larger fauna. The forest is now quiet, as the last flock of birds have likely took to the skies weeks ago.

Reflection

As this is the final update to this blog, I must reflect on this little microcosm of Centennial Woods. What did I enjoy most about my spot? Well, I think what I like most about my spot is the tranquility of it. It’s very pretty for starters, the log-bridge is a quaint natural wonder and the trees sheltering the small stream and gravel bar give a feeling of comfort and peace. Adding to that the soothing trickle of gently running water that you hear as you stand on the gravel, the place honestly would be a great meditation spot if it weren’t for all the mud (a towel would do the trick for that anyhow). Even though this blog is over for the foreseeable future, I will still be returning to this little spot periodically through my time at UVM.

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.