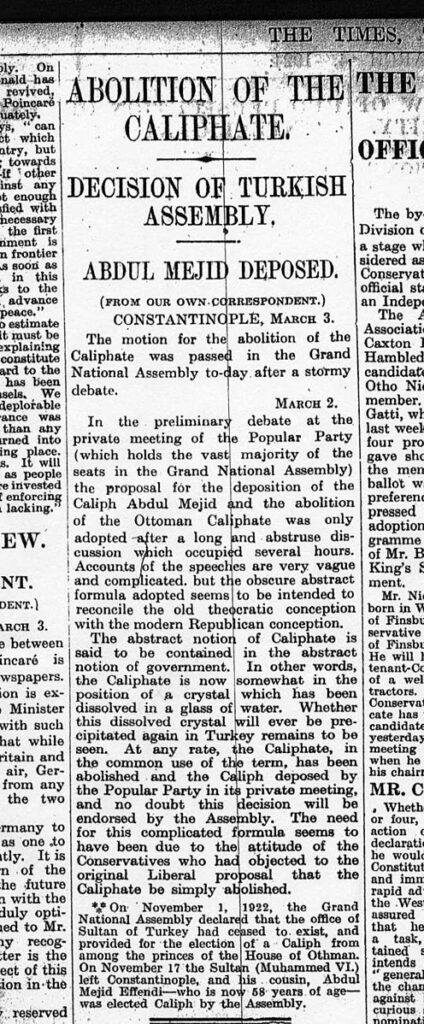

Published on March 3rd of 1924, this article in the Times of London begins by stating, “The motion for the abolition of the Caliphate was passed in the Grand National Assembly today after a stormy debate.” This momentous decision marked the end of the Muslim imperial era. In the postwar era, Turkish elites believed that imperial structures were obsolete, and hoped to embrace Western culture and civilization through the process of secularism.

Later on in the article the Times writes,

“The proposal for the deposition of the Caliph Abdul Mejid and the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate was only adopted after a long and abstruse discussion which occupied several hours. Accounts of the speeches are very vague and complicated, but the obscure abstract formula adopted seems to be intended to reconcile the old theocratic conception with the modern Republican conception.”

This paragraph expresses a common sentiment shared by Western countries regarding the nature of the imagined Muslim world: that there is an inherent incompatibility between Islam and modernity. Repeatedly using words like “vague,” “complicated,” “abstract,” and “obscure” in reference to the Turkish political process is proof of Turkey’s tangible “foreign-ness” in the eyes of the West.

Assimilating to Westernized ideas of democracy, law, and political organization turned out to be difficult for Turkey, due to historic processes of racialization and homogenization of the imagined Muslim world. This racialization and homogenization of Muslims finds its roots in a centuries-long process of imperialism and colonialism. This process creates a global paradigm in which Muslims are seen as a race, rather than a religion, and in which diverse Muslim practices are homogenized into a single stereotyped idea of what a Muslim looks like, acts like, and believes. The results of these processes are often manifested in popular images of Muslims as backwards, despotic, or ill-equipped for modern processes and structures. Writes Morgenstein Fuerst,

“Religions are not races—Islam is not a race—but Islam and its practitioners are racialized. … Depictions of Muslims show them possessing inherent, unchanging, and transmittable characteristics. These are decidedly racialized classifications: Muslims cannot escape these traits; they are imagined to be part of the fundamental composition of what and who is Muslim. To be otherwise, in effect, would indicate that one is not Muslim.”

In the context of Turkey’s nationalist movement, despite beginning a European process of secularization, modernity, and nationalization, the historic racialization of Muslims would continue to mark Turks as incapable or unfit for Western models of reason, law, and organization.

Many Muslims trace the caliphate to the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632. Although the responsibilities and powers of this position were not initially clear, for the early Muslim community, the caliphate acted as a temporary successor to the Prophet Muhammad. The position was passed from Abū Bakr to the Abbasids in Mesopotamia, and eventually to the Ottomans in the sixteenth century. Throughout these centuries, the caliphate represented different things and manifested itself in different ways. For some Muslims, it was a religious figure, for others it was a political position, and others didn’t worship the caliphate at all. In 1924, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey voted to strike down this religious institution, along with all other interactions between Islam and the Turkish state. In this act, the newly-secular Turkish Republic was formed.

The global Muslim response to the abolition of the caliphate was varied. Some Muslims felt that the fall of the Ottoman Empire was the last great Muslim empire falling victim to an ever-encroaching colonialism. Others felt a sense of betrayal by Turkey. As a symbolic figure of Muslims across the world and an Islamic institution, with the abolition arose questions like: to whom does the caliphate belong? And why does Turkey have the power to abolish it? The function of the caliphate as a symbolic figurehead for a persecuted religion in the age of imperialism and colonialism is worth recognizing.

In The Idea of the Muslim World, Cemil Aydin introduces a socially-imaginated separation between a civilized West and an uncivilized, racialized, and second-class East. The racialization of Muslims as people unfit for Western models of progress, in which these models are socially-determined as superior, is crucial for analyzing the abolition of the caliphate. In a tumultuous post-war period, attitudes towards the East and West, religion and secularism, and progress and traditionalism were all up in the air. In this moment, Turkey chose secularism, sovereignty, and European models of progress. This decision confirms a global dichotomy in which modernity can no longer equate to Eastern models of thought, but rather becomes tied to the West.

Turks recognized that the abolition of Islam’s figurehead was a chance to conform to dominant ideas of progress and modernity, in which secularism was a key requirement. In this sense, Turkey employs what Faisal Devji coins as “apologetic modernity,” a process through which Muslim claims to modernity are defined solely as a response to their lacktherof. The formation of the Turkish Republic acts as a response to the processes of homogenization and racialization which depict Muslims as inferior and incapable of modernity, and can be read as a defensive move to prove their capabilities.

As Elizabeth Hurd points out in The Politics of Secularism in International Relations, Turkey’s step towards secularism was not straightforward. Turkey employs laicism, a type of secularism through which religion is sequestered to the private domain and excluded from spaces of modern power and authority. However, as religion, secularism, and politics are not unchanging and unmoving objects, any attempt to grasp and control their interconnections is difficult. Historic imaginations of Islam have also conflicted with this process. Hurd points out “contemporary references to … ‘natural’ links between Islam and theocracy, suggestions that democratic secular order is a unique Western achievement, and the sense that Islam poses a special kind of threat to the cultural, moral, and religious foundations of Western ways of life.” Laicism functions as a result of comparisons between what Hurd calls “the realm of the sacred and the realm of the profane.” It exists through a historic exclusion that marks Islam as anti-modern, uncivilized and irrational, in which the “secular” is the opposite of Islam and the traditionality that it represents.

Making our way back to this same article from March 3, 1924, the Times writes,

“The abstract notion of Caliphate is said to be contained in the abstract notion of government. In other words, the Caliphate is now somewhat in the position of a crystal which has been dissolved in a glass of water.”

The Times doesn’t really define what this metaphor means. In analyzing it, I think of how everything that the caliphate once represented in a single figure now finds itself dispersed throughout Muslim communities, institutions, and believers across the world. In many ways, and for many people, this change was negative. It removed a figurehead, symbolized a loss to colonialism, and signaled weakness and lack of centralized faith leadership. It could also be considered an illustration of the superiority of Western cultural, political, and social structures.

This article shows how the future of what the Muslim world would look like and act like was uncertain. Uncertainty existed not only in terms of Muslim identification with a central figurehead, but also in how the Muslim world was viewed by outsiders. Islam is a religion that spreads across multiple continents, manifests itself in varying forms, and is expressed differently in different individuals, but when the caliphate was abolished, the ability for outsiders to place Islam as a concrete thing into a neat box became much more difficult. In this sense, this crystal metaphor makes me wonder if the dissolution of the caliphate can be analyzed as a recognition of diversity within the Muslim world. Can the existence of multiple diverse Muslim existences be read as a defiance to the historic homogenization of Muslims? If the abolition of the caliphate permits Muslims to exist outside of these created, racialized, homogenized boxes, does this diversity represent and create a more true modernity?

Bibliography

Abolition of the Caliphate in 1924 as reported in the Times of London, 3 March 1924. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Abolition_of_the_Caliphate_in_1924_as_reported_in_the_Times_of_London,_3_March_1924_01.jpg [accessed October 2019].

Aydin, Cemil. The Idea of the Muslim World: a Global Intellectual History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019.

Davison, Andrew. “Laiklik and Turkey’s ‘Cultural’ Modernity: Releasing Turkey into Conceptual Space Occupied by ‘Europe.'” in Remaking Turkey. Ed. E. Fuat Keyman. Lexington Books, 2007.

Devji, Faisal. “Apologetic Modernity,” Modern Intellectual History, 4, 1 (2007), pp. 61–76.

Hassan, Mona. “Manifold Meanings of Loss: Ottoman Defeat, Early 1920s” in Longing for the Lost Caliphate: a transregional history. Princeton University Press, 2016.

Hurd, Elizabeth Shakman. “Secularism and Islam” in The Politics of Secularism in International Relations. Princeton University Press, 2008.

Majeed, Javed. “Modernity,” Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Ed. Richard C. Martin. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. 456-458. Gale Virtual Reference Library.

Morgenstein Fuerst, Ilyse R. “After the Rebellion: Religion, Rebels, and Jihad in South Asia.” Humanities Futures, Franklin Humanities Institute. Duke University, September 7, 2018. https://humanitiesfutures.org/papers/after-the-rebellion-religion-rebels-and-jihad-in-south-asia/