What is an untapped natural resource? The definition being (of a supply of something valuable) not yet used or taken advantage of. One may think of forests or geothermal hot springs. But instead, it is not what we are talking about here, it’s who. Muslim women and girls for years have been seen as ideal subjects of reform and modernity. A common thought has risen that for a country to be modern, girls need to be educated and in turn will uplift their country from its wide range of social problems. Specifically, girls’ education campaigns often posit girls in the global South as either heroines with extraordinary potential or as victims of poverty and patriarchal cultures to be freed by their counterparts in the global North. These binary subject positions reduce the complexities of the lives of girls and have often been used to legitimize western interventions.1 This desire to intervene exists in a realm where Muslim women are seen as a homogenous group in need of saving, where for reform to take place an “ideal girl” is created who has the ability to transcend her class boundary, and where liberal ideas are viewed as the only correct ideas.

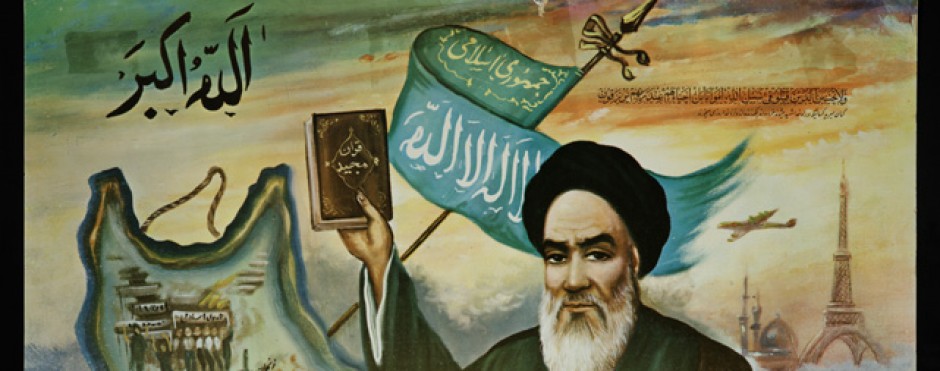

Muslim modernism and pan Islamism were aimed at a western audience in an attempt to counter the racism that justified their mistreatment. Muslims themselves strategically essentialized a notion of the Muslim world that contradicted the lived and local experiences of Muslim societies and was a strategic tool of foreign policy. Countering essentialism demands looking at history and political contexts which are typically ignored.2 It is this viewpoint that gave way to the image of the oppressed Muslim woman in need of saving and of Islam holding her back. Instead of asking questions that explore the history of the development of repressive regimes in the region and the United States’ role in that history, people want to know about the culture and religious beliefs of the region. These types of questions artificially divide the world into separate spheres—re-creating an imaginative geography of West versus East.3

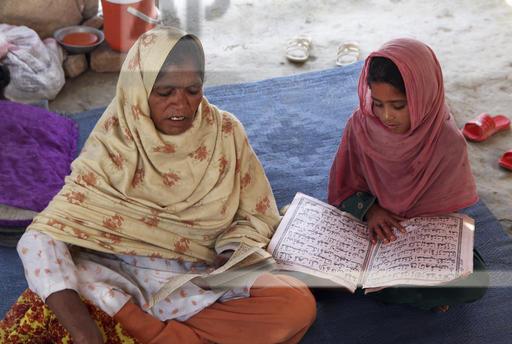

Through the project of nation building, modernization, and development the “ideal girl” subject is defined. The educated girl becomes the empowered girl and development campaigns solidify the idea that Muslim girls and empowered girls are not one in the same. With the supply of education to girls comes the hope that it will prevent early marriage and pregnancy, and will create girls who will be able to enter the labor force, pull themselves out of poverty and contribute to the national GDP. This is an incredible belief that one individual can wield this much power, it is also an incredible burden. Even when a girl demonstrates the capability and potential of a girl who stays in school, given the low quality of education in public schools, any family that seeks to reap the promise of upward mobility via education must partake in expensive private schooling. This is particularly challenging in countries with large populations of lower-middle class families. It is not Islam that creates these barriers to a solid future but economics. Education is viewed and consumed differently by low-income girls who viewed it as a commodity that they consumed today in order to reap its rewards in the future and for girls from upper-class backgrounds education conferred a form of respectability that opened doors to better marriage prospects.4

This “turn to the girl” in development can be situated within the context of neoliberalism, which prioritizes individual autonomy, choice, and agency, and places the burden of improving one’s life on individuals themselves. But this ability is often available only to white, middle-class girls.5 In Susan Moller Okin’s essay, “Is Multiculturalism Bad for Women?” her argument rests on the assumption that liberal culture is the acultural norm and should be the universal standard by which to measure societies. Those who fall short are the barbarians outside the gates.6 Why do we invalidate and ignore the ways women are already navigating their spaces and impose this universal standard? Why do we impose a singular notion of what is right when in different countries what constitutes “right” can be any variation of things? In, I Am Malala, we find evidence of women’s tenacity within socioeconomic and political constraints where empowerment and agency may or may not look the same as that proposed by western liberal feminists. Here, women seem to be working to establish their rights within local frameworks, and against domestic and global patriarchies.7 What fits one does not fit all, whether that is how to navigate education within different class structures or what an empowered Muslim woman looks like. What is known is that in order for these ideas to be contested we must question general beliefs and explore the history of the issues at hand and cannot place all reasoning for things at the feet of religion alone.

Bibliography

1 Shenlia Khoja-Moolji. Forging the Ideal Educated Girl. University of California Press, 2018, page 99

2 Aydin, Cemil. The Idea of the Muslim World: a Global Intellectual History. Harvard University Press, 2017.

3 Lila Abu-Lughod. Do Muslim Women Need Saving? Harvard University Press, 2013, page 31

4 Shenlia Khoja-Moolji, 2018, page 4,110,122

5 Shenlia Khoja-Moolji, page 99

6 Lila Abu-Lughod, 2013, page 84

7 Shenlia Khoja-Moolji, page 122

Ayesha Khurshid. Islamic Traditions of Modernity: Gender, Class, and Islam as a Transnational Women’s Education Project. Gender & Society, 2014.

Hackett, Conrad, and Dalia Fahmy. “Economics May Limit Muslim Women’s Education More than Religion.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 12 June 2018,

Image: Ton Koene, 2010, Photograph, 2728 x 1832 4.48 MB, VWPics via AP Images, http://www.apimages.com/metadata/Index/TKO10495/e445cd30814644d0b477ff4cc6792445/52/0