In Memoir as Iranian Exile Cultural Production, cultural anthropologist Amy Malek writes that the cultural production of exile makes possible new codes, inscriptions, and identities that can uniquely exist outside of hegemonic powers (Malek 356). Uniquely too is the transformative space visual artists occupy, as producers and products of mediascapes. Malek writes that exiles are deterritorialized. This is to say that these inscriptions do not belong to them and yet these powers and structures that marginalize them can at the same time be the sites through which such ideas can be challenged.

Two visual artists who are creating these new meanings through visual grammars are Iranian photographer Shirin Neshat and Muslim American Saba Taj. I define visual grammar most simply as the way artists are able to communicate without words. The discourse of political, social, and historical events act as texts that can be read upon image, and artists are able to dismantle and assemble new texts by questioning its relationship with image.

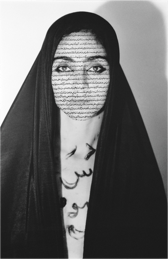

In the photo series Women of Allah Neshat writes literal text onto the bodies of her subjects. She simultaneously reconfigures the orientalist gaze through Persian writers while mediating upon the political constructions of Muslim women. In the mixed media series An-Noor Taj uses portraiture to place Muslim American women outside of the everyday contexts through which they are seen.

Neshat and Taj are located in different exiles, different mediums, and are invested in different projects. Despite this, both create visual grammars that not only help us evaluate and analyze media representations of Muslim women globally, but they also answer the age old question, who is the Muslim Woman?

Shirin Neshat is an Iranian visual artist. Born in 1957 in a small town near Tehran, Neshat  was college educated in the United States and travels between New York and Iran. In the image entitled “Unveiling” from the larger 1993-4 black and white photograph series Women of Allah, a woman directly faces the viewer, wearing a veil that reveals her neck and chest. The skin visible is covered in calligraphy. In other photographs in this series, some women hold rifles and guns.

was college educated in the United States and travels between New York and Iran. In the image entitled “Unveiling” from the larger 1993-4 black and white photograph series Women of Allah, a woman directly faces the viewer, wearing a veil that reveals her neck and chest. The skin visible is covered in calligraphy. In other photographs in this series, some women hold rifles and guns.

Much of Neshat’s work explores the orientalist lens through which the West renders Muslim women voiceless and vulnerable. In this series, Neshat’s visual grammar is communicated through the work of Tahereh Saffarzadeh and Forough Farokhzad, two Persian poets born in the 1930s. While Saffarzadeh is interested in martyrdom and femininity, Farokhzad speaks on sexual desire. However, both poets center women, desire, and love through social critiques and both of their works were banned during the Iranian Revolution.

Neshat’s use of these poets is complex given the relationship between power and discourse discussed in Representations of Post-Revolutionary Iran by Iranian-American Memoirists. Seyed Mohammad Marandi, an Iranian postcolonial academic, and Ghasemi Zeinab Tari, a professor of American Studies at the University of Tehran, write that public perception in Iran is shaped by text and narrative not wholly historical. Further that the same powers that make certain cultures for Malek is the same that limits access to discourse and thereby shapes the public mind (Marandi & Tari, 150).

While Neshat’s work documents, she is neither memoirist or ethnographer. However, her incorporation of two artists creates a sort of feminist genealogy and thereby provides an alternative grammar to make coherent Muslim women.

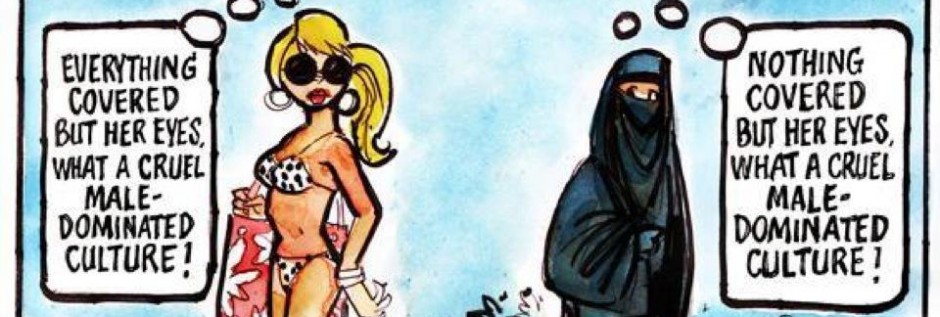

To better understand the implications of this reversal I turn to Chadors, Feminists, Terror by Professor of Gender Studies at Rutgers Sylvia Chan-Malik. Chan-Malik makes the connection between United States media representation of the 2009 Green Movement, protests against the corruption and reelection of President Ahmadinejad, and the protests by women following the Iranian Revolution. Chan-Malik illustrates how intersecting structures such as second wave feminism, secularism, and nationalism created the image of what she calls the figure “Poor Muslim Woman,” what I call more specter than figure given the simultaneous erasure and hollow visibility, that haunts and informs post-9/11 United States.

I lean on Chan-Malik’s idea of racial-orientalist discourse as one that I believe Neshat is speaking against, and yet I want to imagine Neshat’s visual grammar as one that seeks to do more than place a gun in the hands of the Poor Muslim Woman. In an interview Neshat says: “In Islam, a woman’s body has been historically a type of battleground for various kinds rhetoric and political ideology.”

This is certainly true when some might reduce the bodies of Muslim women into field guides. However, to loan Neshat’s own metaphor, the merging of body and poetry assembles a visual grammar as a guide as well, to take up arms against Chan-Malik’s racial orientalist discourse. Perhaps to do this messy work of deconstruction is indeed in the hands of Muslim women and the women that have come before them. Or more simply in Saffarzadeh’s own words, “O, you martyr/hold my hands/with your hands.”

Decades after Neshat’s series, in North Carolina Saba Taj, a Queer Muslim artist, is interviewed by the Huffington Post. She is asked whether the current political climate has changed the work that is expected from her by galleries and buyers. She writes:

“Some people want Islamic patterns and calligraphy from me. And others—hijabs and high heels, or women in burqas making out— the kind of shock value that capitalizes on stereotypical representation and seems “feminist” or “progressive” but is still rooted in racism.”

It is clear in the 2013 series An-Noor that Taj is concerned with this expectation and meets it with subversion. For this project, Taj accepted submissions of photographs by American Muslim women, and uses the background of the portraits as a space to locate them abstractly.

In the mixed media image on canvas “Rebel” shows a hijabi woman wearing a shirt with the title of the image. Against her is background of red, gold, and brown, made up of lines and swirls, creating stars and crescents.

In another portrait entitled “Maesta” a woman and her three children stand, gold halos around their heads. Against her is a background consisting of the American flag: blue beneath yellow stars, red and white stripes, and swirls everywhere.

In my favorite, “Lioness” a woman sits on a pillar made of bricks, and holds a book and sun flower while closing her eyes to the bright yellow sun above her.

Her mediation on light, and the use of sun and brightness in her work is a deliberate choice by Taj. The title An-Noor translates as the Light, coming from the 24th chapter of the Quran. This chapter most notably contains the verse of light, interpreted literally and mystically by Sufis, poets, and philosophers. Light upon light, Taj’s women are soaked and wondered by it, divine and loving.

What is so unique about the grammar Taj engages with is how she places women in a kind of religiosity without making them seem to be from the past or from a distant land. These women wear t-shirts and jeans. Some wear hijab and some do not. All vary in skin color.

Taj is not interested in direct or singular readings of her work just as she is not interested in a direct or singular geographic origin of Muslim women. Instead, her inspiration is multidirectional due to the diverse participation of Muslim American women. This inclusion is similar to the way Neshat uses poetry to create a feminist genealogy. It is also similar to the way there is not an attempt at memoir or ethnography.

Yet, it is important to consider the unique geographic location that Taj occupies that alters this genealogy. She ends the Huffington interview with this final thought:

“I hold a strong awareness of how and what I created could potentially be used against Muslims, to push Islamaphobic narratives (of homophobia, of patriarchy), but that if I try to make my art invincible to misinterpretation— it will lose its quality.”

Taj is specifically constructing a grammar of kinship and sisterhood that positions the identity of Muslim American women as one of hybridity. She does not attempt to reconcile religion and nation, or reiterate American-ness despite Muslim-ness. This is especially important given how the discourse of war on terror and more recently the Muslim Ban seek to rigidly divide these two identities.

And so I end this by asking most simply what grammar can we use to read Muslim women out of the spaces in which they have been captured. Out of prisons and detention centers. Out of the arsenal of white women, politicians, and national rhetoric.

In her biography, Taj mentions that she is interested in diaspora, inherited trauma, and apocalypse. If Malek is correct, that exiles have become deterritorialized, stuck within in between spaces and untethered to land, I wonder to what extent we can consider art as a means towards this apocalypse. Towards the mass destruction of nonconsensual and damage based representations. Towards desire instead. Towards Taj’s light and Neshat’s hands.

Bibliography

CHAN-MALIK, SYLVIA. “Chadors, Feminists, Terror: The Racial Politics of U.S. Media Representations of the 1979 Iranian Women’s Movement.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 637 (2011): 112-40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41328569.

Marandi, Seyed Mohammd, and Tari, Ghasemi Zeinab. Representations of Post-Revolutionary Iran by Iranian-American Memoirists: Patterns of Access to the Media and Communicative Events. Reorient 2, 2017.

Malek, Amy. “Memoir as Iranian Exile Cultural Production: A Case Study of Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis” Series.” Iranian Studies39, no. 3 (2006): 353-80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4311834.