by Gaetano Martell0

The subject of Islam’s role in the world is dense and rife with misinformation. It is not uncommon to see media portrayals and depictions of Muslims that use stereotypes to define them and promote a monolithic view of Islam as a whole. The specific area which this piece will focus on is the way in which this affects Muslim reform in particular, and how people tend to view this in the west. But first, a discussion is needed on what exactly it is that people, particularly Westerners, think needs reforming.

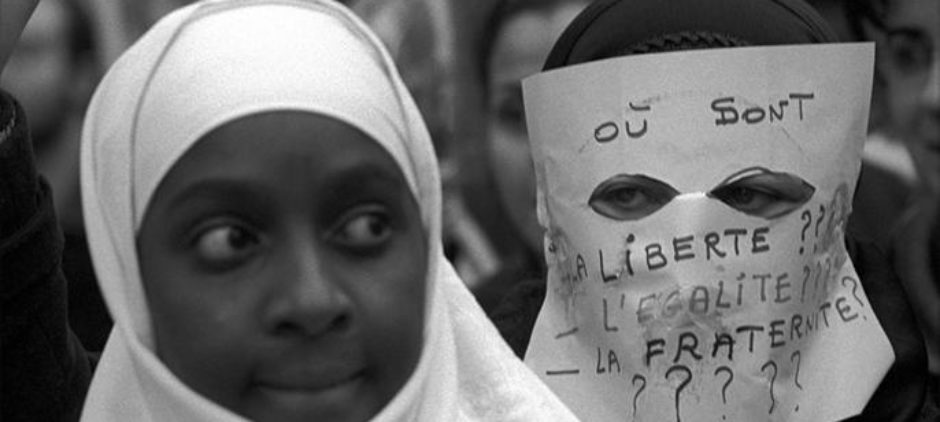

via ArtStor

Political discussions both on the left and on the right usually involve some sort of talk about the so-called Muslim World (Aydin, The Idea of the Muslim World, ch. 1). Among educated Western intellectuals, there is much talk about what the west should “do” with the Muslim world, and the debate tends to be split along the lines of how open we should be to it. Often in media, one can find many conversations about how particular barbaric practices are common within the Muslim world; typically the conservative figures will speak in condemnation of it, and the liberal figures will defend the cultural context in which they do it, but the fundamental question of the debate is itself misinformed.

Probably the most famous example of this tactic is Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations, a work which paints extremely broad strokes across the world along religious lines and which pays very little attention to nuance. The idea promoted here is that Islam is flawed in its essential form, so much so that its members will somehow manifest that essential flaw and thus cause the destruction of the world, without the intervention of the west (Huntington, Clash of Civilizations).

This viewpoint is is obviously heavily elitist, but it nonetheless bleeds into the way Western intellectuals see reform in what they call the Muslim world. Another typical trend within these circles is the call for the need of some vague reform by some entity somewhere (preferably western) tackling the vague problem of, for example, the way women are treated somewhere in the Middle East. To say that there are problems that need reform is true, but it is very often unspecified and does not take into account the places which have made such reforms or are already doing so.

Since this piece is criticizing people for not being specific, it is time we got specific. Two examples of Muslim reformers who took it upon themselves to try and solve particular problems are Malala Yousafzai and Maajid Nawaz. I picked those two because of how vastly different they are from each other and how effective they are in their respective fields.

Malala Yousafzai has become known around the world as a symbol for standing up for the right of women and children to be educated in Pakistan, for which she was famously shot by the Pakistani Taliban. This started when the Taliban had issued an edict banning such parties from schools, which inspired her to become an activist. She has since started a school in Lebanon for Syrian refugees.

Yousafzai has received criticism by quite a large set of parties, including the criticism that she is conforming to Western norms by advocating for education within her demographic. It would be important, then, to note that education for such people in Pakistan is not a new thing, and that the desire to abolish it is quite particular to the Taliban. This is demonstrated by reference to Pakistan’s former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, a woman who was very well-educated and qualified to do her job, and who Yousafzai has credited as an inspiration.

For Yousafzai, the idea of reform for education has less to do with religion than with power structures within her country. It could be easy to misinterpret her reform through Western eyes as a reform against Islam, but for her, education has always been normal and sought after among her social class in the majority-Muslim country she lives in. Free and compulsory education is guaranteed in the Pakistani constitution. Rather than the simplistic claim that Islam has a problem with educating women and children, a closer look at the situation will show that there is a conflict between Pakistani Muslims about the issue of educating women and children, and many people fall on both sides.

Maajid Nawaz is a former extremist and has since been acting against extremism through his work as an author and radio host, as well as his counter-terrorism think tank. In the past, he joined an extreme fundamentalist Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir, for which he was imprisoned in Egypt for five years. During his imprisonment, he studied and changed his views, and has since been advocating for secular Islam as well as ideological reform for extremists.

Nawaz serves in more intellectual circles in his area of reform, because, while he did not preach violence during his time as an extremist, he did preach an ideology that he believes gave way for extremists to act violently. Currently, what he is fighting for is for less fundamentalist interpretations of Islamic texts to prevail within his own community. An apt comparison more familiar to Western readers would be between some conservative fundamentalist evangelical Christians, such as Jerry Falwell, who interpret the bible in condemnation of homosexuals and who give a lower status to women, and more liberal Christians whose interpretations contradict that reading of the text. Nawaz is after a similar sort of reform.

Both figures here represent different forms of what D.V. Kumar calls “engaging with modernity”. Where a common western conception of modernity would probably be antithetical to the Pakistani Taliban’s view on education, the reality is that this was an entirely new thing, and that for Yousafzai, engaging with modernity meant standing up to modernity in support of her country’s already existing legal commitment to education. For Nawaz, who has spent a long time on both sides of the extremist debate, the new wave of religious extremism is also a form of modernity which he wants to resist in favor of a more secular version of Islam (Kumar, Engaging with Modernity).

It should be noted that Nawaz’ views can come under criticism from some intellectuals for conforming too heavily to Western values. In Faisal Devji’s piece “Apologetic Modernity”, Devji criticizes a view similar to Nawaz’s as expressed by Fazlur Rahman.

“Rahman, himself a celebrated exponent of Islamic modernism, traces its origins to the period of European dominance in the nineteenth century and to the emergence throughout the Muslim world of efforts at grappling with the fact of Europe’s intellectual and political hegemony. It is in this context, Rahman thinks, that these efforts coalesced in a movement he calls Islamic modernism, which he defines in terms of its partialities and unsystematic character: a movement consisting on the one hand in a defense of Muslim beliefs and practices against European criticism, and on the other in an attack on these same beliefs and practices in the terms of European criticism” (Devji, Apologetic Modernity, p. 63).

Though this can be considered a problem for Nawaz, as it was a problem for Sayyid Ahmad Khan, it shows exactly the problem with the idea of the Muslim world; that there is profound disagreement among its members, and thus it is not a unified front against Western values as people like Huntington would suppose.

Nawaz and Yousafzai are quite different from one another. Yousafzai is far younger, and is a practicing Muslim, while Nawaz, as was mentioned, considers himself a secular Muslim. Yousafzai is Pakistani, Nawaz is English (though he has Pakistani heritage), and their reform is in entirely different fields. This is all to point out that these two are individuals with separate motivations and who work in different parts of the world for different reasons, but both in their own ways are Muslim reformers. This is a great example of why painting a broad stroke and calling it “Islam” is harmful, as it erases the varied nuances that make individuals and communities and which color particular situations.

Works Cited

Aydin, Cemil. The idea of the Muslim world: a global intellectual history. Harvard University Press, 2017.

Devji, Faisal. “Apologetic Modernity.” An Intellectual History for India, pp. 52–67.,doi:10.1017/upo9788175968721.005.

Hesford, Wendy S. “Introduction: Facing Malala Yousafzai, Facing Ourselves.” JAC.

Huntington, Samuel P., et al. The Clash of Civilizations? : the Debate. Foreign Affairs, 2010.

Kumar, D.V. “Engaging with Modernity: Need for a Critical Negotiation.” Sociological Bulletin, Aug. 2008.

Nawaz, Maajid. Radical: My Journey out of Islamist Extremism. Lyons Press, An Imprint of Rowman & Littlefield Press, 2016.

Thomas Dworzak. OSLO. October 2014. Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi. http://library.artstor.org.ezproxy.uvm.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_37890060. Web. 20 Feb 2018.