Turkish modernity is neither religious nor secular. Pinar Ilkkaracan’s work is an example of the actualization of this complicated dichotomy shown through the actions of both the Turkish government and its citizens. Pinar Ilkkaracan is one of Turkey’s leading activists for women’s rights. She has helped found several NGOS including WWHR: Women for Women’s Human Rights. Her committees and research have spurred reforms in Turkey. Ilkkaracan reported in a paper for the Institute of Development Studies that progress was slow due to the structure of both the current and previous government since

“the rights granted to women by Kemalists aimed to destroy links to the Ottoman Empire and to strike at the foundations of the religious hegemony rather than at establishing actual gender equality…thus, the Republican ideology also instrumentalized women, this time as the protectors of secularism, just as the conservatives before them held women as emblematic protectors of conservative family values and the social order” (Ilkkaracan, “Reforming the Penal Code in Turkey”).

The activist committee ran into a lot of frustrations in their attempts for legal reform. One of the many penal codes the committee failed to change in 2005 was a “a legal loophole that limits the scope of the article to only a certain type of honor killing, such as family assembly verdicts, or as if it only exists in certain regions where certain customs prevail,” though 35 amendments were made in the previous year to other penal codes (Ilkkaracan). In 2010, Turkish officials amended part of the Constitution but ultimately made little change and created further evidence for the non-transparency and conservative nature of the government.

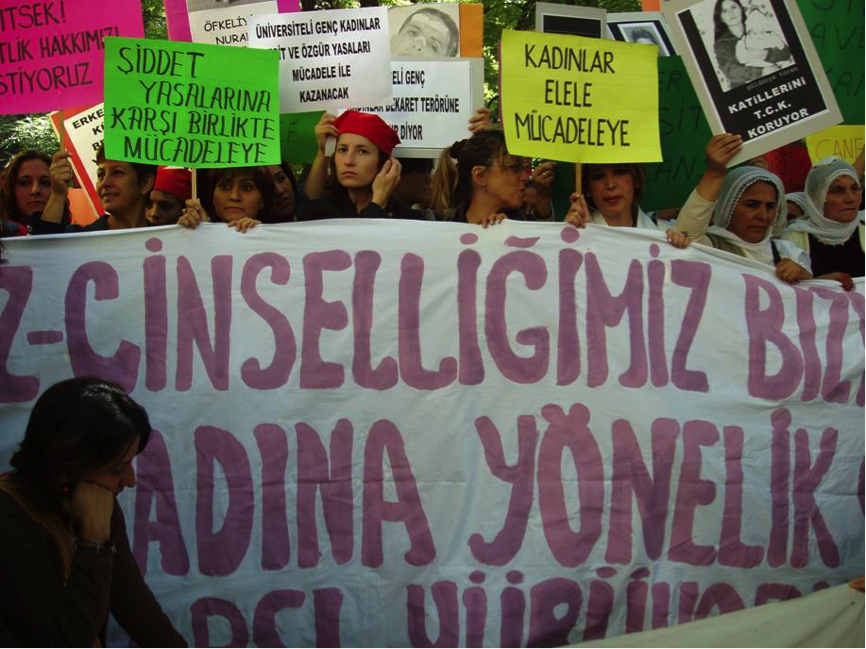

Previously, in 2007, protest meetings exemplified this tension, when the ideologies of traditional Islam and secular Islam came together in the form of protests against the low representation of women’s rights within the government. While some argued that the protests that went on did not best represent the people, especially those led by women’s NGOs, the support of civilians for the protests raised awareness for the issues and diverse identities present in Turkish society. Furthermore, even while secularism was seen to be in contrast to Islam, Muslim demonstrators carried flags of Ataturk. The Justice and Development Party, a socially conservative political party, came into power in 2002 using the tensions over the legality of a mandatory headscarf to gain support.

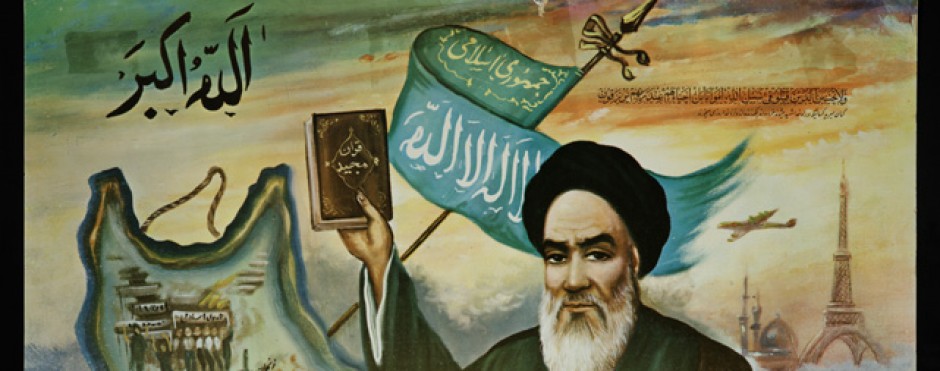

While the Justice and Development Party, or the AK Party, could be accused of using fundamentalist ideologies to gain power and suppress minorities, the party actually rose to power in the aftermath of the spread of secularism. The previous structure “beginning with Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, forcibly secularized many Muslim societies, subjugating religious authority to increasingly intrusive lay supervision and stripping it of institutions it previously monopolized, such as courts and schools. At the same time, experiential secularism spread in the daily practices of Muslims” (Martin, “Islamic Secularism”). Even while secularism was taking hold in Turkish ideologies, there was still a tension against the secular modernity of the West.

In September of 2014, “hundreds of women marched in front of the parliament chanting ‘our bodies and sexuality belong to ourselves’.” This motivated the government to withdraw the offending penal code, part of which recriminalized adultery, which was an unprecedented move. However, there were many roadblocks before there was progress. In the NGO report to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, of which Ilkkaracan and her NGO were a part, it reports that “in the period from 2004 to 2009, Turkey did not formulate or enforce the legal amendments necessary toward eliminating discrimination, and thus failed to meet the commitments set forth by the Committee; many demands by women’s groups for the recognition of women’s legal rights and the prevention of gender discrimination encountered resistance from the political authorities”(Ilkaracan).

One of the main differences between Turkey and Euro-American contexts, is that “there is not a distinct separation between religion and other aspects of people’s lives. Islam is both din wa dunya (religion and the world). The basic conflict here is not necessarily between religion and the world, as was the case in Christian experience; rather, it is between the forces of tradition and the forces of modernity” (Monshipouri, “Secularization”).

For activists like Ilkkaracan, the headscarf debate was one of the biggest ways in which women’s rights influenced politics. Secularists were very anti-headscarf because they were afraid that the mandatory headscarf was “going to open the door to punishing Islamic crimes — like apostasy or adultery” (Friedland, “Islam, Gender, and Democracy in Turkey”). These issues over secular versus religious law also brought into question identities and what it means to be a Muslim for many Turks.

Nazife Sisman, another activist, has been able to reconcile questions over women’s rights using secularist ideologies and religious arguments. For example, she believes in feminism but with religious regulation because “secular feminism denies the most important hierarchy, not between men and women, but between God and humans… The Creator gave women and men different natural “duties”: respectively to give birth and raise children and to protect and support those women. A man’s economic “burden,” she says, is a “compensation for not giving birth.” It would be unjust if women could not count on that male support” (Friedland). Arguments like Sisman’s have been used by women to justify the employment prioritization of men over women, though most feminists of this mindset still believe in the reduction of violence against women that “doubled from 2008 to 2012, according to the parliamentary Human Rights Commission. The country is also wracked by startling rates of child brides — nearly 7,000 girls were married between the ages of 13 and 17 over the past decade” (Jones, “Turkish Activists Say Their Country is Sliding Backward on Women’s Rights). Ilkkaracan is less concerned with reconciling religious and secular ideologies and focuses more on the fact that “Turkey was rated 120 out of 136 countries in terms of gender gaps in education, health, politics and economics by the World Economic Forum”(Jones).

Ilkkaracan often struggles with the government concentrating on “how they can make the laws more in line with their conservative ideology” instead of “of concentrating on protecting women who suffer from domestic violence”(Jones). In 2010, Ilkkaracan sat with dozens of other representatives from feminist organizations and heard current President Erdogan declare that he did not believe in gender equality. However, this did not deter her. Since then, she has continued to do work especially with women’s shelters and victims of domestic violence who are “less likely to receive state subsidies or financial support and benefit if she does not wear a headscarf,” despite the AK party’s official policy. Illkaracan hopes to continue to work in the four areas she sees the women’s movements concentrating: “women’s labour force participation – which is the lowest among OECD countries, political representation – which is in a pitiful state (The NGO KA-DER pushed for a quota of 30% during the 2007 and 2011 elections but the increase was minimal), violence against women, and the reform of the Turkish constitution to ensure gender equality”(Ilkkaracan, “The Turkish Model”).

The consistent changes and actions by the AK Party have helped redefine the position of Islamic women in Turkish modernity. Whether through social matters, such as a headscarf, or legal matters, such as protection from domestic violence, the ideologies surrounding gender in Turkey are changing. NGOs, such as the one founded by Ilkkaracan, are responsible for these changes due to persistent petitions, marches, and research. However, the tensions between the secular and religious perspectives in Turkish society and government are still very prevalent in these issues and can both create change and cause problems for reformers like Ilkkaracan.

Bibliography

Friedland, Roger. “Islam, Gender and Democracy in Turkey.” The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/roger-friedland/islam-gender-and-democrac_b_1155048.html

Jones, Sophia. “Turkish Activists Say Their Country Is Sliding Backward On Women’s Rights.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 18 Apr. 2014. Web. 14 Oct. 2015.

Monshipouri, Mahmood. “Secularization.” Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Ed. Richard C. Martin. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. 615-616.

Ilkkaracan, Pinar. “Reforming the Penal Code in Turkey: The Campaign for the Reform of the Turkish Penal Code from a Gender Perspective.” Women’s Human Rights– New Ways Association, Sept. 2007. Web. Oct. 2015.

Ilkkaracan, Pinar. “The “Turkish Model” : For Whom?” OpenDemocracy.

50.50, Nov. 2011. Web. 14 Oct. 2015

“Islamic Secularism” Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Ed. Richard C. Martin. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. 614-615

The Executive Committee for NGO Forum on CEDAW – Turkey Women’s Platform on the Turkish Penal Code. Shadow NGO Report on Turkey’s Sixth Periodic Report to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Rep. no. 6. Women’s Human Rights – New Ways Association, July 2010. Web. Oct. 2015