Kristen Smith

REL195: Islam and Modernity

Professor Morgenstein Fuerst

When we think of ‘the west’ and ‘the east’ it is tempting to imagine them as singular, homogenous entities in opposition to each other. But, we know that this is wrong on many accounts. Within ‘the west,’ there are numerous geographical, ethnic, racial, ideological, political, religious, and economic contradictions. This can also be said of ‘the east.’ If we can agree on this point, then let’s apply it to nation-states. We know that identity is not static, especially in terms of countries. So why do we try to pin nations as having one singular identity? Why do we assume that “the west does it best” and every country is dying to eat at our lunch table?

Is it possible that Turkey does not want to be considered western? Even though they are trying to get into the EU, perhaps this is less a popularity contest and more a power move. I was in fifth grade when Mean Girls was released, and I can’t help but draw parallels of Cady and Regina’s relationship to Turkey’s relationship with the west. Let me be clear – I am not comparing American teenage girls to nation-states and centuries of history. What I am equating are the effects of power, authority, and hierarchy on identity and perception, individually and collectively.

Let’s run with this Mean Girls analogy, shall we? Regina George is ‘the west’ who believes everyone wants to sit at her lunch table, dress like her, speak like her, and essentially be a replica of her. She regards herself as the top dog who can manipulate anyone to do what she wants. But this is her perception. Suppose Cady Heron is similar to Turkey. Cady is a new student who can hang with the “art freaks” while also blending in with “the plastics.” When Cady arrives at her new school, she couldn’t care less about Regina and the school’s social hierarchy. It isn’t until she is personally slighted by Regina that she strategizes with Janis and Damian on how to sabotage Regina. But their plan is not as easy as they originally hoped. In an attempt to take Regina George down, Cady spends more time with the plastics, adhering to their dress code, nuanced rhetoric, and deceitful behavior. In doing so, Cady loses the identity she imagined herself to have prior to meeting the plastics. She lies to her friends and family, intentionally fails her math tests, and loses the respect of her peers and teachers. In an attempt to beat Regina at her own game, Cady gets swept into conforming and suffers the detrimental effects.

Using the power dynamics, hierarchy, and exclusivity inherent in Mean Girls, a similar relationship can be explained between Turkey and ‘the west.’ I argue that it cannot be assumed that Ataturk wanted his nation-state to be western with the creation of the republic of Turkey. I use Devji’s argument in “Apologetic Modernity” as a basis to frame Turkey’s attempt to create their own identity as a secular democracy in a Muslim-majority country. While Devji argues that the Indian Muslims were successful in creating their own modernity, I argue that Turkey is failing in its attempt and losing the identity they originally sought. The two reasons I utilize are Turkey’s prohibition of religious dress in public spaces, and their censorship of the press and regularity of imprisoning journalists. Finally, I refer to Göl’s “The Identity of Turkey: Muslim and Secular,” to argue that Turkey can very well be a secular, modern, democratic, Islamic state, but they need to reevaluate current policies and how beneficial they are to their citizens.

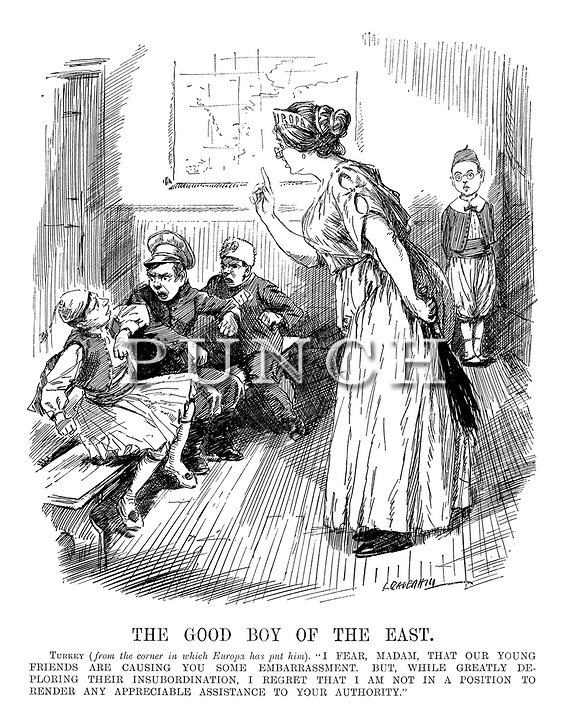

I do not think that Kemal Mustafa, Ataturk, wanted Turkey to be considered part of the west. Rather, he wanted to establish a unique nation-state that was not fully western or eastern, but something of its own kind that was unlike any other. Ataturk used Islam as a means to “unify diverse ethno-linguistic groups” and fight a war defending their homeland against foreign European forces (Yavuz 2000, p.22). Turkey’s identity was established on religious and territorial grounds. The state used Islam as the commonality to fight off foreign armies in conquest of Turkey’s land. Once the Turkish people were united and they established a common identity, Ataturk viewed Islam as an obstacle to Turkey’s international power and reputation. Subsequently, Turkey was established as a secular nation. Their identity was still immensely rooted in Islam, but Ataturk believed that Islam would compete with the people’s loyalty to the new nation. Religion in Turkey “had not to be so much separated from the state as subsumed by the state” (Delaney 1995, p.188). Ataturk embraced Pan-Turkism and not Pan-Islamism in order to create and sustain Turkish nationalism. One example of disestablishing Islam was adopting European dress and banning the fez, implying that Ottoman dress was unsuitable for modernity (Olson 1995, p.164). Although law prohibited the fez, there are reports that during Ataturk’s rule the prohibition was not strictly enforced. “’It was said that one could encounter people wearing such clothes on streets quite frequently’” (Olson 1995, p.162). The degree to which the public adhered to Ataturk’s ideas oscillated depending on political and ideological factors. Men who did not follow the “Hat Law” were not immediately or commonly punished (Olson 1995, p.165). Since the “Hat Law” was not punitively enforced, perhaps this was nothing more than a check on a list to please Europe’s idea of modernity. We can use this historical example to frame a contemporary issue. It is egocentric of the west to think that Turkey wants to be western. Even if Turkey is fighting to get into the EU, perhaps this is a power move and not an act of flattery. No Regina, Janis Ian is not and never was obsessed with you.

Punch Cartoons. The Good Boy of the East. Digital image. Edwardian-Era-Cartoons-Punch-Magazine-1913. Punch, 2015. Web. 1 December 2015.

Punch Cartoons. The Good Boy of the East. Digital image. Edwardian-Era-Cartoons-Punch-Magazine-1913. Punch, 2015. Web. 1 December 2015.

Turkey’s attempt at beating the west at their own game is not far off from Devji’s argument that Indian Muslims were able to successfully create their own version of modernity without the British even knowing. As the British underestimated the power in refusing to dialectically engage with Indian Muslims, in favor of the latter, so has the west misjudged Turkey’s self-knowledge of its geographical, religious, and cultural positioning (all data: Devji 2007). While the west may, in one sense, regard Turkey’s geographical, historical, and religious identity as a ‘backwards’ weakness in comparison to Europe’s centrality, it is actually a “luxury” that Turkey is well aware of.

However this is where Turkey is not successful like Devji argues of Muslim apologetic modernity. Instead of being a distinct not fully western or eastern nation-state, Turkey has become engrossed in trying to be an international superpower that has the democratic, secular ideals of European modernity, while also the religious and cultural ties to what they deem non-western. Consequently, the focus on their international image has led to a strong neglect of their citizens. This is not to say that identity is static and Turkey must return to Ataturk’s original ideas of what the republic should be. The identity of an individual, culture, or nation is fluid and not confined to a singularity or a categorization; but two key issues in contemporary Turkey imply that the current policies are more harmful than auspicious.

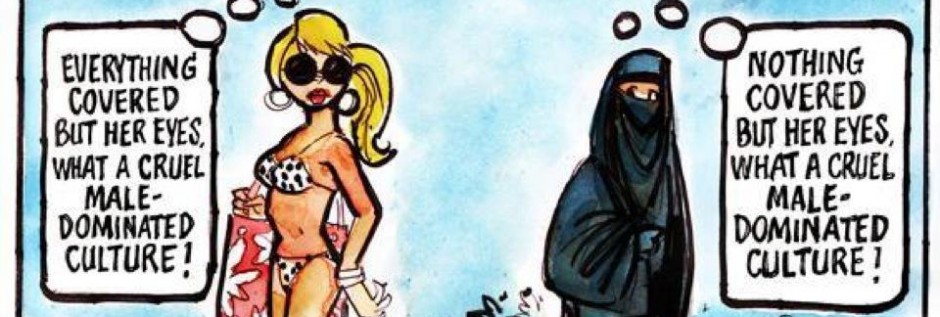

In 1982, Turkey prohibited the wearing of the veil in government offices and universities, both public and private. Since then, conflict has emerged discussing women’s freedom, the religious right to wear the veil, and gender equality. The European Court of Human Rights and the Turkish Constitutional Court both claim that the ban is “a necessary and reasonable response to the threat allegedly posed by fundamentalist Islam to Turkey’s secular democracy” (Vojdik 2010, p.662). Policing women’s bodies by eliminating their choice and agency in the decision to wear the veil or not is more detrimental than fruitful. The ban is interfering with women’s education and careers.

In the mid-1980s, female university students in Istanbul participated in protests, demonstrations, and hunger strikes in an effort to abolish the ban, arguing that it violated their right to religious freedom. Twice the Higher Education Council eliminated restrictions on wearing the veil in 1989 and 1991, only to later be annulled by the Turkish Constitutional Court. Challenges to this ban have continued, often preventing female students wearing the veil from taking their university exams and sometimes leading to their suspension (Vojdik 2010, p.669). Turkey’s attempts at creating their own secular, modern, and democratic identity are negatively impacting the rights and education of its citizens. It is positioning the constitution and supposed democracy over the rights and advancements of the people.

In addition to preventing female students from furthering their education by prohibiting religious dress, Turkey has a sticky past with free press. Turkey has decades of history of a close relationship between the media and the military. Even though the ownership of the media has changed, the plague of catering to the government and conflicted financial interests has persisted. Frequently journalists are targeted, fired, and imprisoned under the arbitrary anti-terrorism laws. According to Freedom House Delegation, other tactics used by the Turkish government are buying off or forcing out media moguls, wiretapping, and intimidation. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is known for attacking journalists by name after they write critical commentary (Corke et al. 2014, p.1, 2). He has made public speeches asking media owners to silence opposing columnists. Leading journalists have admitted that this has caused a strong self-censorship. In January 2011, there was a live soccer game shown on all Turkish channels. During the opening ceremony, the Prime Minister was forced to leave early after a succession of boos, jeers, and protests directed at him. The following day, if newspapers covered this event, it was not on the first page and was given a vague, neutral one-line sentence (Arsan 2013, p.449, 450).

The latest report from Reporters Without Borders (RSF) released in February 2015 placed Turkey 149th in the free press index out of 180 countries surveyed. Turkey climbed five places from the previous year as a result of releasing many arrested journalists, but this does not necessarily mean the state is improving its free press, censorship, or public freedom of information. Journalists are still targeted. In the 2015 index, Turkey placed higher than Russia, Iran, and China, but was behind countries such as Venezuela, Cambodia, Afghanistan, and Algeria that also have widespread arrests and intimidation of journalists (Zeynalov 2015). Turkey may claim that it is democratic, secular, and modern, but it is its impairing citizens and imprisoning journalists, impeding free press and public freedom to information. Much of the opposition that the government prohibits is from the Kurdish press and population. In the 1990s, there were direct forms of violence, such as unknown killings of Kurdish journalists and the bombing of newspaper buildings (Arsan 2013, p.448). Today, many of the journalists and activists who are arrested are Kurds (Corke et al. 2014, p.3, 4). There is much to be improved in Turkey in terms of freedom and human rights.

It is egocentric of the west to think that Turkey currently or has ever wanted to be western. Similar to the power dynamics in Means Girls, as Cady did not want to be Regina George, Turkey never wanted to be western. Ataturk did not fight off foreign European armies to create a nation-state that was yearning to be western. While the fez was banned, the “Hat Law” was not enforced. Turkey’s attempts at joining the EU are not a form of obsequiousness. Perhaps Turkey is trying to beat the west at their own game, and in the fashion of Devji’s Indian Muslims successfully creating their own Islamic, apologetic modernity, Turkey wants to create their own secular, modern, democratic nation-state separate from the west. However this is where Turkey is failing. Similar to Cady losing herself in the plan to sabotage Regina, Turkey has implemented laws that are detrimental to its citizens, such as the prohibition of wearing religious dress in public spaces and the censorship and lack of free press. While Turkey may be failing, this is not to say that they cannot create their own nation-state that is democratic, modern, and secular. But they need to embrace their Islamic identity that united them against other European forces after World War I. They need to stop oppressing women by eliminating their agency in deciding whether or not to wear the veil, stop persecuting and neglecting the Kurdish population and reach a peaceful compromise, and provide the Turkish citizens with a full free press and public freedom to information. Göl contested Huntington’s claims that Turkey is a bridge between the west and east and a ‘torn country’ (Göl 2009, p. 796). She argues that Turkey is neither a bridge nor a torn country between western and Islamic civilizations. Turkey can be established as Islamic and secular, in addition to being democratic and modern, but it is necessary for the citizens and politicians to evaluate and adjust their laws so individuals’ rights and freedoms are not compromised.

Bibliography:

Arsan, Esra. “Killing Me Softly with His Words: Censorship and Self-Censorship from the Perspective of Turkish Journalists.” Turkish Studies 14, no. 3 (2013): 447-462.

Corke, Susan, Andrew Finkel, David J. Kramer, Carla Anne Robbins, and Nate Schenkkan. “Democracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in Turkey.” Freedom House (2014): 1-20.

Delaney, Carol. “Father state, motherland, and the birth of modern Turkey.” Naturalizing power: Essays in feminist cultural analysis (1995): 177-99.

Devji, Faisal. “Apologetic modernity.” Modern intellectual history 4, no. 01 (2007): 61-76.

Göl, Ayla. “The identity of Turkey: Muslim and secular.” Third World Quarterly 30, no. 4

(2009): 795-811.

Olson, Emelie A. “Muslim Identity and Secularism in Contemporary Turkey:” The Headscarf Dispute”.” Anthropological Quarterly (1985): 161-171.

Punch Cartoons. The Good Boy of the East. Digital image. Edwardian-Era-Cartoons-Punch-Magazine-1913. Punch, 2015. Web. 1 December 2015.

Vojdik, Valorie K. “Politics of the headscarf in Turkey: masculinities, feminism, and the

construction of collective identities.” Harv. JL & Gender 33 (2010): 661-685.

Yavuz, M. Hakan. “Cleansing Islam from the public sphere.” Journal of International Affairs 54, no. 1 (2000): 21-42.

Zeynalov, Mahir. “RSF Ranks Turkey 149th in Latest Press Freedom Index.” TodaysZaman.February 12, 2015. Accessed December 1, 2015. http://www.todayszaman.com/anasayfa_rsf-ranks-turkey-149th-in-latest-press-freedom-index_372416.html.