Andy Jones manages the Intervale Community Farm, all of which lies within the 100-year floodplain of the Winooski River. Last week, I sat down with Andy in his office to hear his perspective on the farm and his strategy for adapting to the extreme weather of climate change.

We are subject to the whims of the river. When I started in 1993, the typical pattern was spring flooding, snowmelt flowing, all related to how much snow pack was in the hills. And when the weather warmed, rain hit the snow pack and came rushing down to lake and inundated some fields. The flood plain looks very flat but it is actually sloping and there are a lot of minor surface undulations, a foot here and foot there make a great deal of difference in terms of actual flooding.

Every speck of ground and building is located within the 100-year of floodplain including where we are right now (in the farm office). The main reason it’s remained in agriculture within the city limits of Burlington is because it’s within the 100-year floodplain. If that were not the case, it would have been housing or something else long ago.

Andy stands in a long tradition of farming at the Intervale. As he acknowledges, “long ago, the land was recognized as quality productive farmland; native peoples farmed here for hundreds of years. Ethan Allen was granted all of it in the 18th century; it’s been farmed entirely throughout the centuries. It’s productive farmland, albeit subject to flooding.”

Was Tropical Storm Irene a game changer?

Water management and flooding have always been our major challenges; the biggest risk factors are not insects, diseases, or market disruptions, but the omnipresent risk and the potential catastrophic outcome of the big flood.

In 2011, when Tropical Storm Irene dumped on us, we were heavily impacted; the entire farm, save 2 acres, was underwater. All of our high land that usually does not flood was flooded and we lost about 12 – 13 acres of crops, which were in the ground.

Unlike a lot of other people, we’d been preparing because we were accustomed to being in a floodplain and having to salvage crops and to move equipment out of harm’s way.

In hindsight we should have started earlier. We certainly didn’t have any idea about the scale and the magnitude; we were expecting a bad flood – we weren’t expecting an Epic flood.

After Irene, Andy explains, there were some things he really had to look at hard. “We expected to have a rough spring the following year and while we didn’t make our spring numbers, we were pretty close, 94-95% of our target. By the following year we were back on track in spades.”

Did the cooperative structure make a difference in customer and membership support?

I think the cooperative structure in the broad sense of the word ‘cooperative’, not necessarily in the legal sense of the word. For some people, the legal cooperative is important and the fact that they own it and have a stake in it is a motivating factor for their commitment. More people joined the co-op as members providing $200 to the farm through their co-op equity membership. For the larger percentage, it’s more about their relationship, they know the farm, they know the people who are the growers, and they understand that we are all in this together. We came up with an arrangement which works for everybody and that was really powerful.

It’s really more about their relationship, they know the farm, the growers, and they understand that we are all in this together…

A number of farmers who were direct market growers were dependent on farmers markets where everything just evaporated. But for us, we had this on-going business because we had people who we were talking to us, to whom we were sending our newsletter, and we were holding events.

From marketing standpoint, I was impressed with the commitment of CSA membership and the model did help us through the overall catastrophe. In order for it to be successful, you need to have a relationship with the CSA members and a good track record.

How does the floodplain make a difference in farm management?

Even though the trend has been toward crazy precipitation episodes, we don’t suffer as much because we have a lot of very sandy well-drained soil.

The irony is the floodplain is dangerous and forgiving at the same time.

We do have about 1/3 of our land that is fairly silty, considerably lower, and more flood prone, so with that land, since Irene, we’ve made some adjustments. I realized I wasn’t going to be able to count on the wetter land to be able to plant early crops and always have to wait and plant crops.

How are you predicting the odds of the weather and evening out production?

When we expect to plant varies year to year, not before the 2nd week of May, sometimes early June. Silty soils hold moisture better so have less moisture stress compared to sandy soils. We’ve been planting later for 20 years but we have lost significant crops in lower fields in the past 5 years, so we plant crops which we can more afford to lose, and which turn over quickly such as lettuce, spinach, and salad greens. With a quick maturation rate, if they’re lost, we can still replant. With the winter share, we’re dependent on growing a lot of root crops, which we need to store. We can’t lose these, as we’re reliant on them for the long sweep of the seasons.

How are you managing different soil types in flood prone areas?

For our silty soils, we bought a raised bed builder a few years ago. We’re not using this on sandy soils as the water drains away. While raised beds don’t help us in the flooding situation, they help in intense precipitation events (2-3 inches or when we have consecutive wet weeks) by preventing saturated soils and root death.

On the sandy side of the farm, we rely a lot on irrigation and we have for 20 years so we have invested in irrigation equipment. And we expect that every year we will irrigate. Last year, August was dry and we were irrigating our vegetables twice a week.

For us, irrigation has been essential; otherwise, we would have lost so many crops as irrigation allows us not only to keep things growing and bulking up, but other crops we can’t even germinate without irrigation.

For us, irrigation is the difference between a crop and no crop.

One of the things we’re blessed with in the Northeast is plenty of water and in this location in particular we have great water resources. We have a big river going by and the ground water is relatively shallow so when we had a well put in to feed our greenhouses, the well drillers we’re so excited that we could get 800 gallons a minute for nothing.

In managing flood prone soils, what benefits have you seen?

Coming back full circle, where we started is to really trying to concentrate resources on the more secure parts of the farm, so that’s the sandy fields. Although we have issues with low organic matter and water management, they are more secure and resilient to weather extremes. We push the yields in a concentrated area, make sure we’re really on top of our game with weed control, irrigation, really optimizing the growth of everything in those areas. When we’re spread out over wider area, we don’t really pay attention to any one thing.

Since Irene, have you suffered more losses due to too much water?

Nothing major. Last year, we lost in late May and early June; we lost ¼ acre – 1/3 acre of spinach and lettuce and 20% of our potato crop. In the whole scheme of things in terms of overall farm output, it was less than 5%.

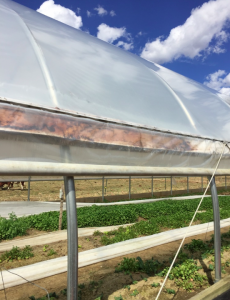

How are you using cover for erratic weather?

Tunnels are major element of overall planned resiliency and an example of concentrating production. We’ve moved all our tomatoes and almost all our peppers inside which contributed to better yields and profitability for both those crops. And it allowed us to grow throughout the year. Since tomatoes are 10% of our overall value and baby salad greens are about the same, if we can take 20-25% of the farm revenue and shelter that from a lot of the weather extreme, that’s been really good.

Intervale Community Farm, March 2016

Have you diversified your market to response to climate change effects?

We haven’t done a lot to diversify our markets and I don’t think that would really help us be more resilient because our market is not our chief constraint. Having that close relationship with our CSA members is as strong and as favorable a market as we could possibly have for weathering climate disruptions.

In general, I don’t think our market has shifted in response to climate change. But I think the fundamental premise of security and diversity in our crops has proven itself in response to upheavals in the weather and climate. Years that it’s cold and wet we have super greens, brassicas, and onion crops which people enjoy, and years when it’s hot and dry, we have excellent melons, tomatoes, and peppers. Almost no matter the weather, we have some things that are really thriving.

If a new farmer came in here today, what advice would you give to her or him?

If they were in a floodplain, I would say, try and get the land that’s the highest land you can, as there are lots of floodplains I’d not recommend people to start a farm or grow vegetables on. It’s pretty hard to build your business without having at least some significant % of your land that is not very flood prone.

So I’d say make sure you have some high land, try to concentrate your production as much as you can on that land, have tunnels, grow a lot of different crops, make sure you either have a highly diverse market or you have a highly committed market – in our case we have a highly committed market. As Andy advises and concludes our talk,

Pay attention to establishing a strong track record of growing good produce in the years that you’re not hampered. Then any goodwill you’ve engendered during that time will be needed and you’ll have it banked against disruptions down the road.